AS appraisals go it was one to take home to mother, especially one who had told you to forget about joining the NYPD during the crack-ravaged 1980s and take a nice, safe job as an accountant instead.

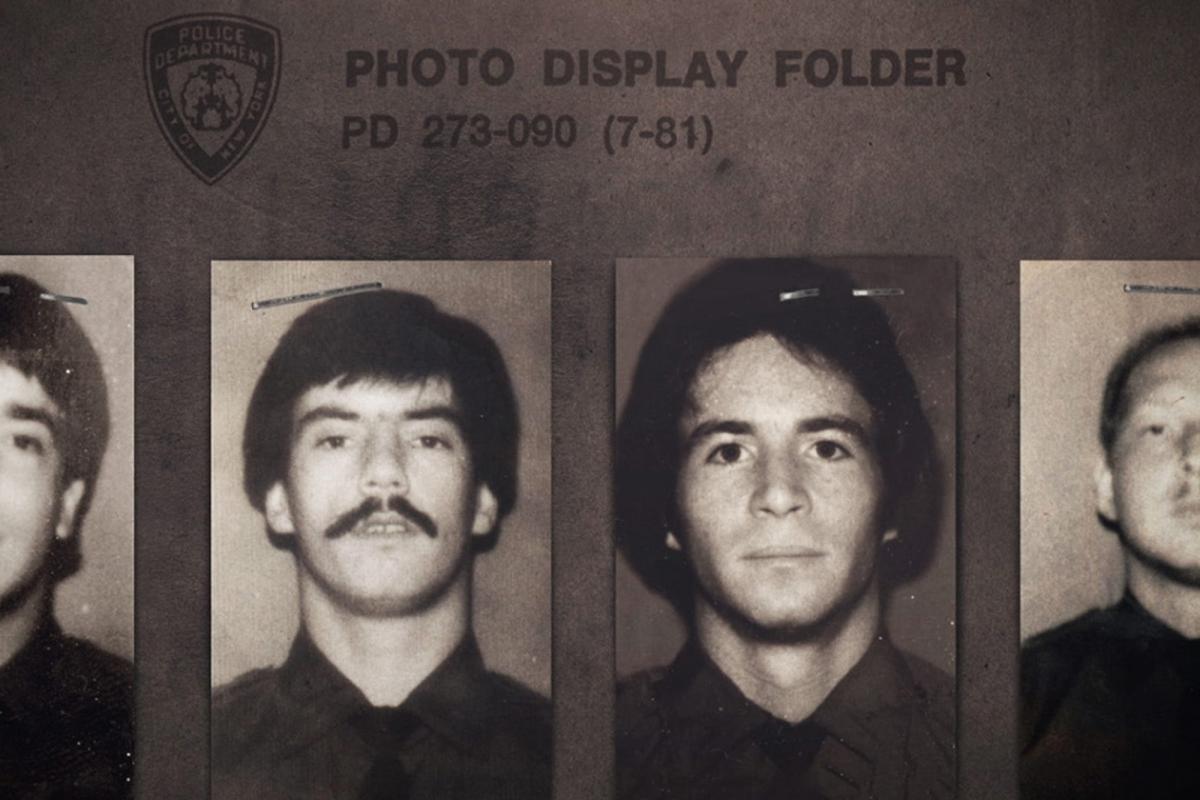

According to his line manager of the time, Michael F Dowd, officer number 79566, had “excellent street knowledge”, he was “empathetic to the community” and he had “good career potential”.

Well, two out of three ain’t bad.

Dowd knew the streets and their problems so well because he had crossed the line from cop to criminal and was stealing and dealing drugs. As for his career potential, the officer the Daily News dubbed “the dirtiest cop in New York” would go on to serve 12 and a half years in jail.

The story of Dowd, his swindling colleagues and their connections to a local drug lord is set out in a blistering new documentary, Precinct Seven Five. Directed by Tiller Russell, the film had its European premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival to toasty reviews and is out on general release next week. As a colleague commented when told about it, “Corrupt cops, New York – what’s not to like?”

The outlaw never goes out of fashion in popular culture. Indeed, the story behind Precinct Seven Five is now to be made into a feature film. Dowd fancies Mark Wahlberg to play him. Dowd is also writing a book. Documentary, book, movie: is Dowd, like that other crossover merchant, mobster turned Mafia informer Henry Hill in Goodfellas, having the last smirk?

Hill’s name comes up a lot in discussion of Dowd. Both from Brooklyn, both one of seven children, both capable of giving good gangster quotes. “As far back as I can remember I always wanted to be a gangster,” says Hill, played by Ray Liotta in Scorsese’s masterpiece, while Dowd declares: “I considered myself both a cop and a gangster.”

In the topsy turvy moral universe of crime and the movies, Goodfellas managed to make Hill seem cool, even if he was, in mob parlance, a rat. Dowd, however, was a bent cop. Could any cachet possibly lie in that? What circle of hellish condemnation might he inhabit?

Your view on that might depend on which Dowd you meet. Over the course of many months, Russell tracked down Dowd and his former colleagues using the same software bounty hunters deploy. Within minutes of getting in the car with Dowd, Russell knew he had the makings of a film. “It was like being kidnapped by a maniac,” Russell told me, “but the most interesting, compelling, equal-parts-hilarious-and-horrifying maniac I had ever met.”

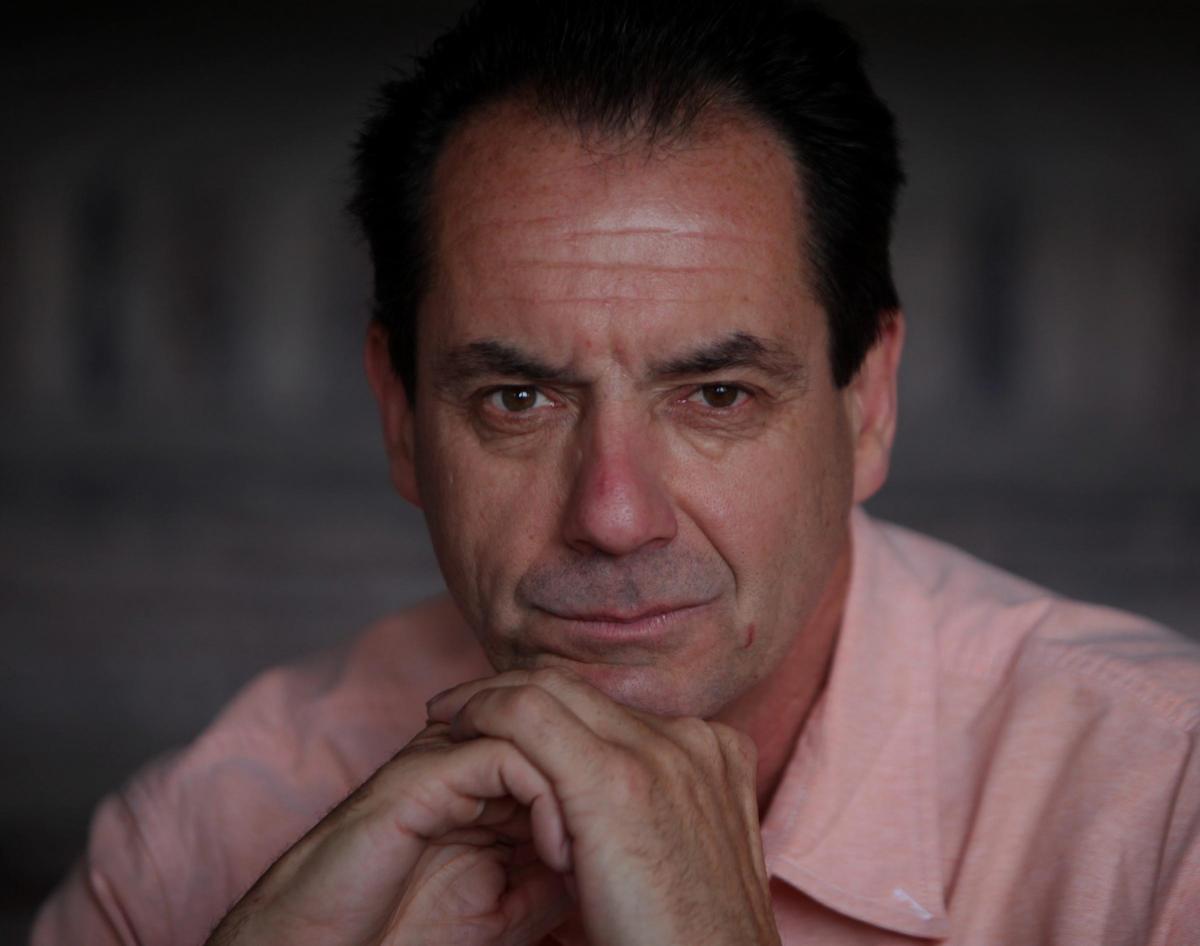

The Dowd I meet in an Edinburgh hotel is jet-lagged but still aiming to charm. He has slept for 12 hours out of the last 16. “I don’t sleep that much in a week sometimes,” he says, his Brooklyn twang making him sound like a cross between Joe Pesci and Daffy Duck. He’s 54 now, an age away from the 20-year-old who joined the NYPD in 1982.

Back then, New York was a dirty, dangerous town, home to 3,500 murders a year (last year: 328). Where the “Seven Five” was situated in Brooklyn was particularly bad. “It was called the Beirut of New York,” says Dowd. “It was just rubble, then a building, rubble, then a building.” And then along came crack cocaine, throwing dynamite on to the bonfire.

Having seen his firefighter father injured, Dowd chose to join the police force, much to his mother’s dismay. He had been two years in the job when he stopped a car being driven by a young Puerto Rican, his pockets stuffed with what Dowd suspected were drug dollars. He could arrest him, but hey, if some of that money was to find its way into Dowd’s pocket … And that was it, the line crossed.

“If I had a choice now to do it again I wouldn’t have done it,” he says. At the time it seemed like a way of poking the department in the eye for his relatively low-paid, high-risk existence. It was also Dowd exerting his independence, telling himself that he was not just another blue-collar schmuck. The risk became addictive, the money rolled in.

For a time, “Mikey” led a very nice life as a cop turned criminal. He was earning $4,000 a week, buying houses, going on lavish holidays, turning up to work in a little, red, very new Corvette. He was often drunk and on drugs. Michael was royally taking the Michael in every sense. Why wasn’t he caught sooner? There were, it emerged later, no fewer than 16 complaints lodged against him. Theories abound, including the department not wanting another scandal so soon after officers were arrested in another precinct. But above all, there was the sense that the blue line would always hold against outsiders. “I never had a fear of getting busted because the cops around me would never give me up,” Dowd said. The same blue line continues to show itself today, though contemporary outrages are far more likely to involve the deaths in custody or police shootings of unarmed black citizens than corruption.

Dowd, by now a father of two, was wrong about a cop never giving him up. Kenny Eurell, like the rest of the precinct, knew that Dowd was dirty. But he went to work with him and before long he, too, was in deep. After a drug dealing operation they had set up was uncovered, federal agents presented Eurell with an offer that, like the one Dowd made to the young Puerto Rican all those years ago, was too good to refuse – help us catch Dowd and you won’t go to jail.

Dowd says being turned in by Eurell felt like being cheated on. Did he love this guy? “Absolutely I loved him, I put him before my family in everything I did. As I look back that’s pretty foolish but that’s the bond that we had, I believed in my heart at the time.”

The documentary ends with Dowd being convicted of racketeering and conspiracy to distribute narcotics. What happened next is the more downbeat part of the tale. “Yeah, it was fun, lots of fun,” says Dowd with a weary laugh when I ask what life was like inside for a former cop. He was placed in solitary for his own safety, locked up for 23 hours a day. After nine months he threatened to hang himself. “On a daily basis it was mentally difficult.”

He was never attacked, but there were “confrontations” with other prisoners. “People just trying to find their own way through prison who were scared, trying to find a weak link, and they thought they could find one in me because I was basically the only white guy in prison alone. Everybody groups up, whether it be blacks with blacks, Spanish with Spanish, white with white. I was the only one without a group.”

After an initial spell in New York he was moved to Florida, more than 1,000 miles away from his family. His wife and children stood by him “as long as they could”. Over the course of 12 years he saw the oldest child 10 times and the younger half that. Today, he says, they have a “respectable” relationship given the circumstances. “I love them and they love me.” He has not remarried, though he has a long-term girlfriend.

Dowd the former cop now works in building services, fixing air conditioning and suchlike. It took him 11 years to get a job after leaving prison. He was untouchable, but not in the Eliot Ness sense. People talk about redemption, he says, about forgiveness, but it is not that easy.

“It’s really not that fair. I’m not asking for forgiveness, I’m just asking to be accepted back into society. It was very difficult. Really, really difficult. I’m fortunate, people don’t have the support that I had when I came home from my sentence.” Even so, there was a point when the road to normality seemed so daunting that he wanted back inside.

It is hard to say to what extent Dowd accepts that what he did was wrong, that he was not some essentially benign Brooklyn Robin Hood, robbing the bad to give to the bent. In the documentary, the lingering anger of the policemen who caught him is obvious. Joe Trimboli, an internal affairs officer, says Dowd’s actions actively contributed to the misery of the neighbourhoods he was meant to serve.

When I put this to Dowd his response is surprising. After musing about grains of sand shifting one way or another he halts and shifts from back foot to front. “You know what, let’s look at it from another angle." According to this angle, Dowd has made it easier for cops to turn in other cops. He has, in short, done the department a favour. “So yes, Michael Dowd is a scourge in the police department but his case opened the door to dozens and dozens of other cases that no-one even talks about. So is there a deflection here? Ah, go ahead and call it what you will but how about let’s just go with the facts?”

I ask if he regrets everything, or just regrets getting caught. He laughs. “OK, see that’s a poke right, isn’t it? So if we could all get away with this it would be wonderful? That’s not fair.”

This is the Michael Dowd who believes he has paid a very high price for his past actions. But there is also the Michael Dowd who got himself an agent when he was released from prison. Then there is the Michael Dowd who, the film shows, was accused of allegedly plotting to kidnap the wife of a drugs dealer and hand her over to a rival cartel. The day he and Eudell, wearing a wire, were meant to carry out the plan was the day Dowd was arrested. Dowd denies any such plan, saying the aim was to rob the woman, not kidnap her. A Drugs Enforcement Agency officer in the documentary says Dowd is “lying”. Russell says: “Well, there are tapes and the tapes don’t lie.”

So what next for Dowd? At the end of Goodfellas we see Henry Hill living in suburban anonymity. “Everything is different,” he says. “There’s no action. I have to wait around like everyone else … I’m an average nobody. Get to live the rest of my life like a schnook.” In reality, Hill did not have the last smirk. He lived in constant fear of being tracked down by his enemies, in and out of trouble again, drinking. Death came via a heart attack. He was 69.

Dowd is sober, he has a job, a family and a partner, he is better placed than many to live a good life. Regrets, yes, he has a few. Had he toed the line he would have been retired at 41 on a full pension. Most of all, he wishes that someone would have taken him in hand when he was younger, pointed out to him that none of this was going to end well.

We’re winding down when this tough-talking former cop grows wistful about his service as a police officer.

“I was a very clever individual when it came to police work. For 10-plus years I was a police officer in very good standing as far as my record is concerned. I could do the job well and I actually loved police work. Police work was a great deal of fun and excitement.

“So looking back, were there fun moments, I’m not going to lie to you. Trips to Atlantic City on someone else’s dime are always wonderful. The Bahamas. Bermuda. But the fact is I wish I’d paid for it all myself and retired.”

Precinct Seven Five (15) opens in cinemas on August 14.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article