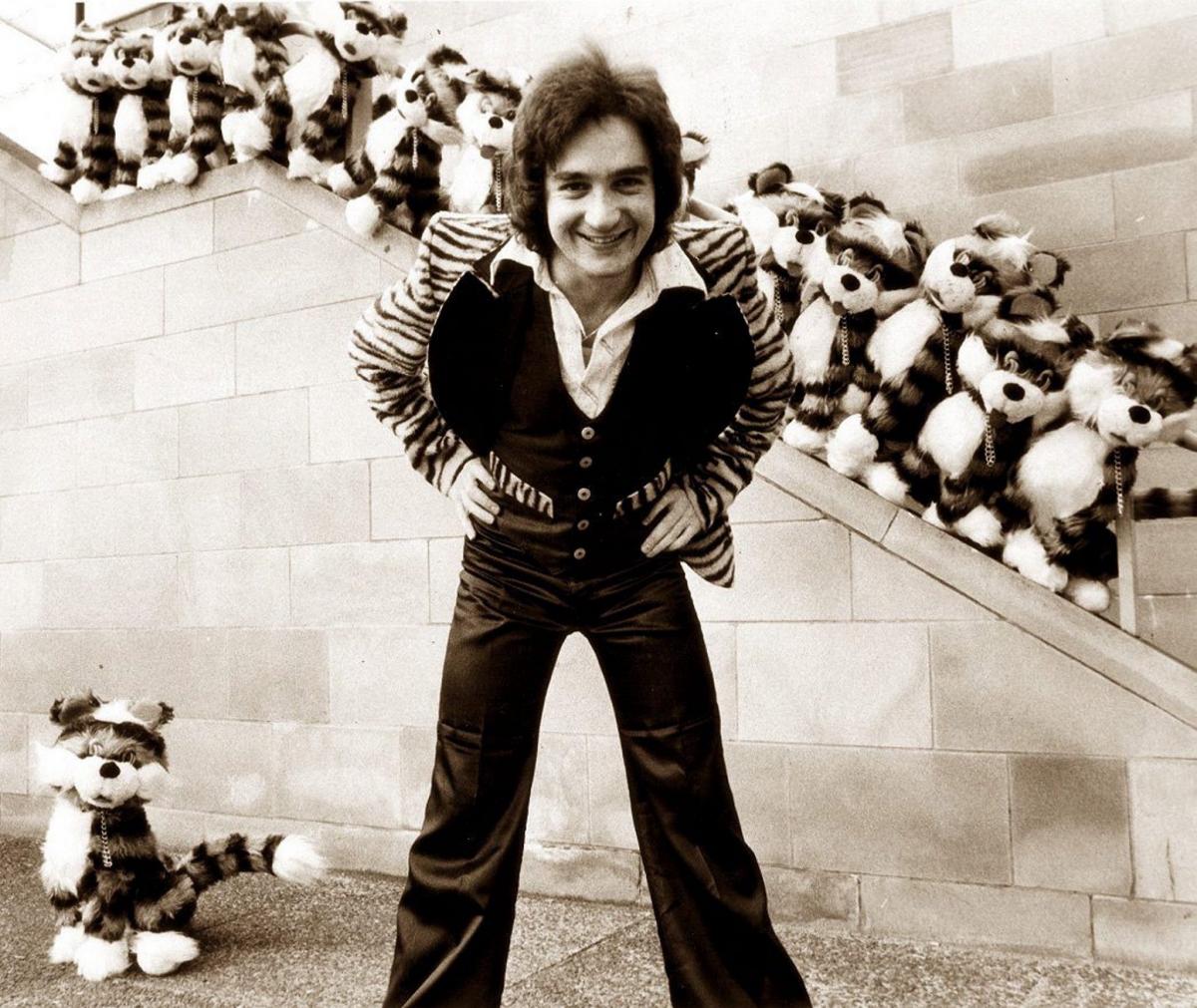

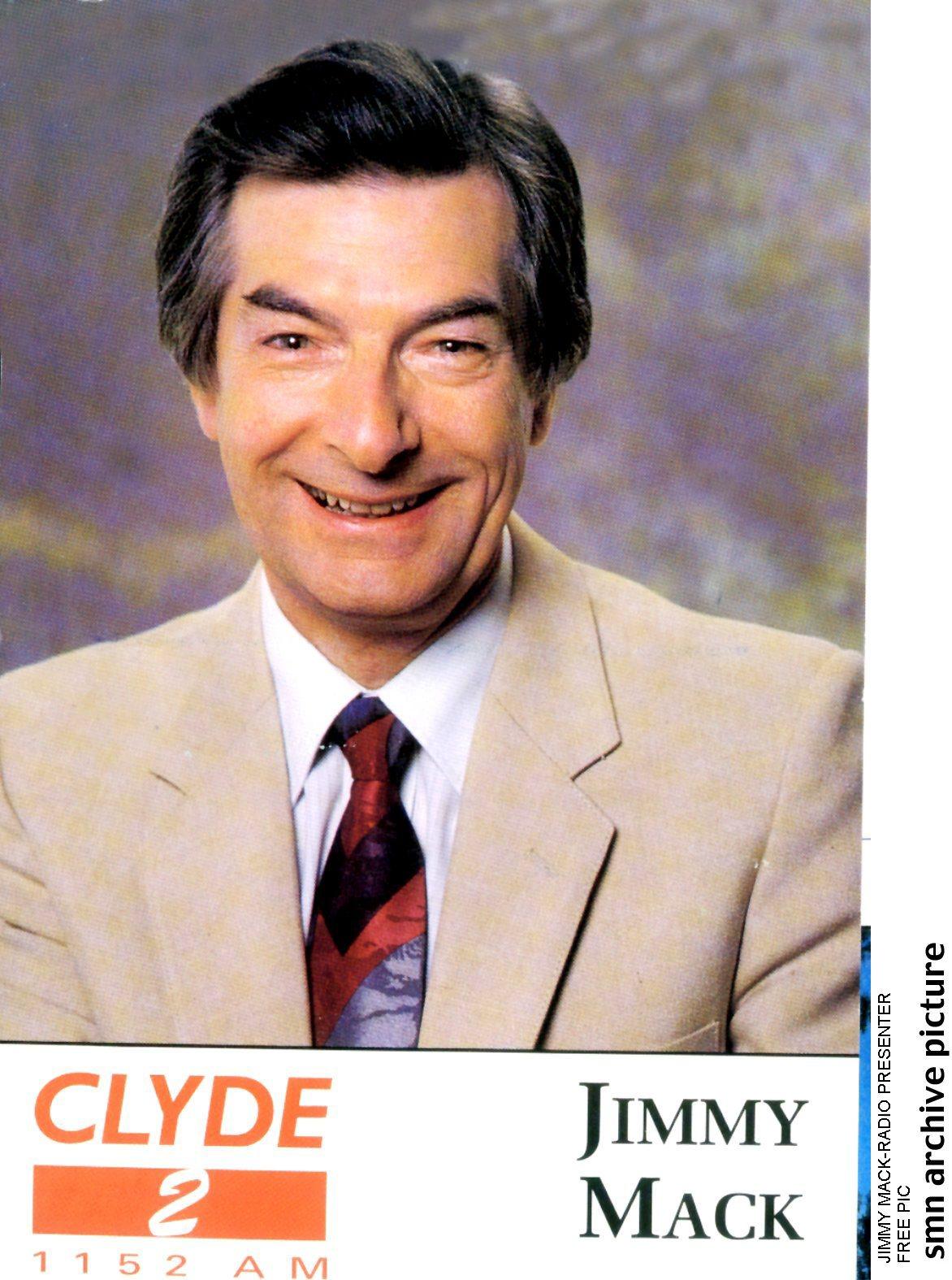

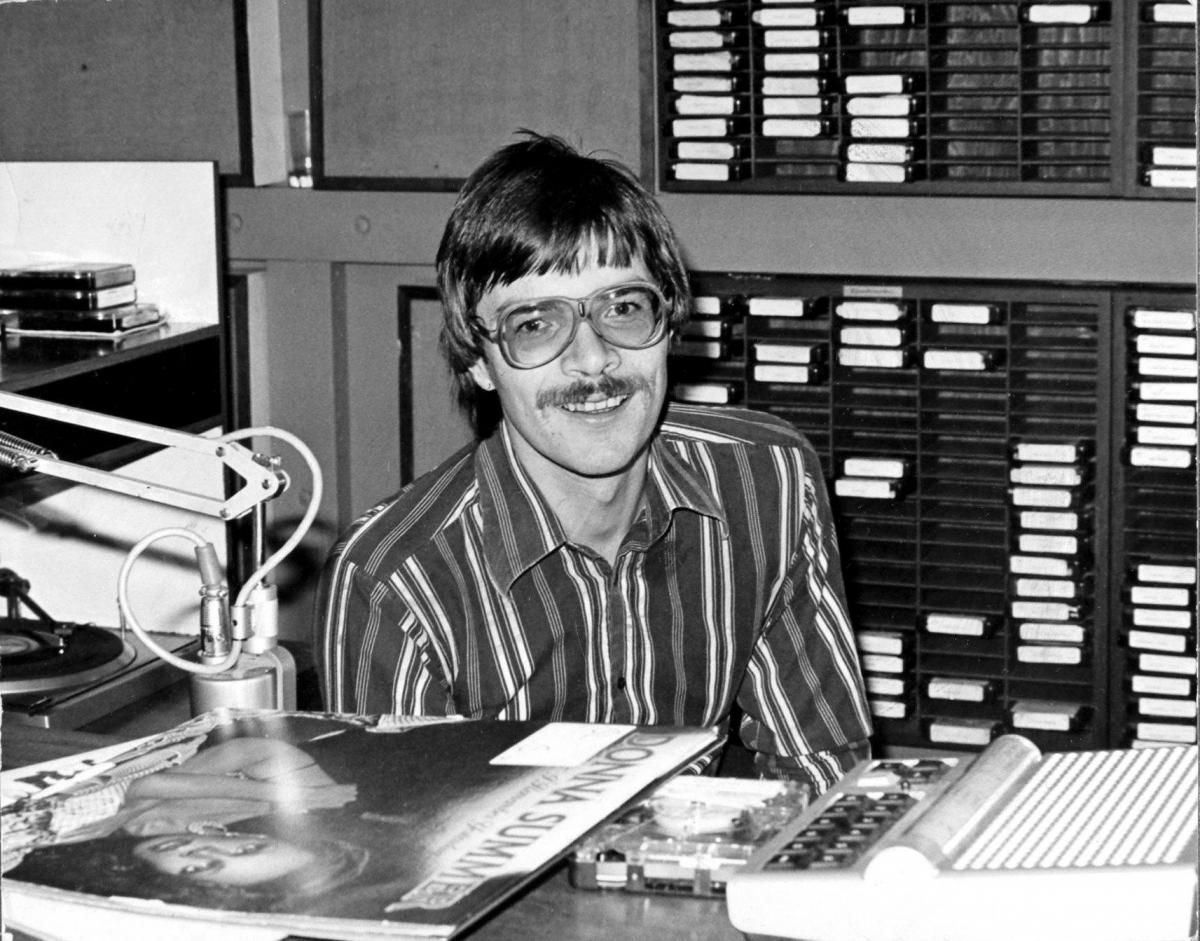

WHEN independent local radio arrived in Scotland in 1974, its USP was its innovative localness, a broadcasting world away from the London voice of the BBC. The new homegrown presenters were immediately adopted by listeners and the likes of Tiger Tim Stevens on Radio Clyde, Eddie Mair on Radio Tay and Nicky Campbell on Northsound became like family.

But these days you could be coming home to find a complete stranger in your living room, or even a rather incongruous former TV presenter talking to you while you’re in the shower.

Local radio is far less local these days. Independent local radio (ILR) stations have grouped into conglomerates and in the process, it’s claimed, become a platform for networked shows, a one-presenter-fits-all broadcasting system, which means the same Scottish voice is heard in Glasgow, Aberdeen and Dundee.

The bigger commercial stations have also leaned heavily in the direction of syndicated celebrity shows coming from London or Manchester, whereby you can hear Emma Bunton on Scottish station Heart or Kate Garraway on Smooth? And while we all love Jason Donovan, do Scots want to hear him link records on Heart from a studio 500 miles away? Can Toby Anstis and co relate to being stuck in a traffic jam on the Kingston Bridge, or behind a tractor in Kingussie?

These changes beg the question of whether local radio stations and their audiences are still on the same wavelength, given the homogenisation of output, but the move to de-localise radio also points up a cultural dichotomy: while the nation is demanding increased autonomy, independent radio in Scotland is becoming more centralised.

Former Radio Clyde presenter Kevin Cameron believes Scotland is losing its voice – and the prognosis is serious. “The major radio broadcasters Bauer Media [which owns the likes of Clyde, Tay, Northsound and Westsound] and Global [owner of Heart, Smooth Radio and Capital] are steadily moving away from homegrown presenters,” he says. “Clyde 1 was originally committed to 20 hours a day broadcasting from within Glasgow, a rule set by Ofcom, and Clyde 2’s local output was 19 hours a day. But from a total of 39 hours a day, it’s now down to 10, a 74 per cent reduction.”

Cameron illustrates how the changes have come about. “Radio Clyde once broadcast Tiger Tim’s evening slot, but when it was taken over by David Farrell, aka Romeo, it was networked across Scotland to seven stations who were left with this single Glasgow voice. Then the Glasgow voice was dropped completely for someone from Manchester. The idea is that radio companies save on the presenter’s fee, the cost of the producer who works on the show and the technical staff.”

But does it really matter if the voice of local radio in Scotland is Mark Wright from TOWIE? Do listeners in Edinburgh care if their evening broadcaster was born in Easterhouse? And is Scottish radio actually under attack from cultural imperialism?

“This isn’t an argument about nationalism,” Cameron maintains. “This is about looking after the Scottish listeners. If you have someone broadcasting from Manchester how can you possibly feel a connection? And if you believe Aberdeen and Glasgow are very different cities, with different senses of humour, why give them the same presenter?”

Big names such as George Michael used to regularly visit stations such as Radio Clyde

Several broadcasters believe the move away from localisation by Scotland’s two big radio companies has been prompted by their desire to become national stations, and by using syndicated presenters they are closer to achieving that. Interestingly, after Ofcom recently turned down XFM’s plans to use Chris Moyles on the breakfast show throughout the XFM platforms, the station's owner Global handed its XFM Scotland licence back to the regulator.

But is this new hybrid radio – part local, part national – an inevitability? Former Radio One and Radio Clyde presenter Mark Page, who has owned two commercial radio stations in Scotland in Perth and Lanarkshire, argues local radio isn’t economically viable.

“When you are selling single-brand packages such as Emma Bunton into a group of stations you can then go after national advertising,” says the Teesider. “And if you do that, you don’t need the teams of local sales staff. The biggest cost by far in running a station is staff and if you can run it on two presenters and a small management that’s what you do.”

Cameron, however, argues the likes of Global and Bauer don’t need to cut staff and run network shows. “It’s called greed,” he says. “The savings they make aren’t that considerable. And they’re at the expense of good local content.”

Page points out Scotland has in fact lagged behind the rest of the UK in local radio going network. “This is because the country has a stronger identity than the English regions.” But surely this is an argument for not diluting the identity with remote presenters? “Yes, it is to some extent, but you have to ask what is local content? Reading out someone’s text?”

Is there more to local radio than that? Cameron says it’s about audiences connecting with a presenter’s humour, shared experience and encouraging talent. “At one time Clyde would bring up the big names such as Elton John to be interviewed by a Scot. Are we now saying Scots presenters don’t have their own style and voice? And if you use network presenters instead, how can you hothouse the likes of Ross King, who has gone on to work in Hollywood?”

Former Clyde presenter Gary Marshall, now co-owner and station boss of Dunbartonshire’s Your Radio, maintains local radio has a sound future – if it goes back to basics. “I was the wee boy who grew up listening to Clyde stars such as Tim Stevens and Richard Park, and what we’re doing at this station is emulating their homegrown success, using local presenters, with the exception being the chart show. What being local means is when it rains on you, it rains on us. And it’s a fantastic tool for selling to local business.”

But can stations such as Your Radio survive without major national advertising? “It’s hard, but it’s doable,” says Marshall, “and now we’re set to go on to Rajar [the audience research chart to which stations subscribe] and when we get official figures that will allow us to chase a slice of national ads as well as local.”

The continual rebranding of radio stations reflects the difficulties owners face. For example, since Scot FM’s conception in 1994, it has gone on to become Real Radio and now Heart Scotland. Saga FM became Smooth and Q96 became QFM then Rock Radio, then Real Radio XS and more recently XFM Scotland.

Adam Findlay agrees the market place is tough. He runs three independent local radio stations – Wave 102 in Dundee, Central FM in Stirling and Original in Aberdeen – but believes localness has to be a priority.

Joanna Lumley at Clyde

“What I find amazing is some big commercial stations pretend they are still local. You hear Emma Bunton backed by localised jingles which suggest she’s in Glasgow, and it’s very disingenuous. If you believe in networking, why try to hide it? Our radio stations don’t believe in networking. Our strength is in not being national. And I think stations such as Heart believe their competition to be Radio 2, not Clyde.”

The station controller lays part of the blame for local radio losing its localness at the hands of the government. “The BBC has a variety of national stations, but commercial radio is restricted to one licence and that happens to be Classic FM [owned by Global]. It’s absolutely insane. What this means is commercial radio is fighting the BBC with one arm tied behind its back.”

Does the strategy of ILR giants Bauer and Global in hiring the likes of Emma Bunton work? “Advertisers follow audiences,” says Findlay. “Personalities only work to a degree. And if you look at commercial radio 20 years on, we’ve got another 150 to 200 radio stations across the UK, but we haven’t increased our audiences. At one time, 50 per cent of the population listened to commercial radio. Today it’s still the same figure. Commercial radio has simply cannibalised itself. We can’t compete on a national level with the BBC so these networked local radio stations are desperately trying to web together a national brand using local licences.”

Findlay believes local radio, if it is local, can be successful. “Aberdeen has doubled its audience in five years and Central FM has had its highest ever listening hours in the past five years. In Dundee there are issues, but we’re working on that.”

Localness has worked for a range of smaller stations in Scotland. “The likes of Sunny Govan in Glasgow seem to survive,” says Mark Page, “but these are almost as hobby stations.”

Tony Currie, broadcaster and founder of online radio station Radio Six International, argues small stations have appeared as a result of a demand for localness, citing Heartland in Pitlochry, a volunteer-run station which has increased its output from a couple of hours a day to 24 hours a day. “It’s great reverse engineering,” he says, “and there are other similar examples such as Two Lochs Radio in Wester Ross and in Shetland.”

Bauer Media, however, maintains it hasn’t gone back on its commitment to local listeners. “Our philosophy is to create locally relevant content [throughout the day],” says a spokesman for Bauer City Network. “Most of our shows on Clyde 1 and other local stations are locally produced and broadcast. Only a small minority of off-peak shows are networked – in Clyde’s case we have only three shows across the entire week that are not broadcast from our studios in Glasgow. One of these is The Network Chart.

“You also have to distinguish, particularly in Scotland, from UK network shows and Scotland network shows. Scotland network shows often have a greater relevance and traction with the audience than UK network shows.”

Do the syndicated shows work in terms of audience figures and advertisers? Bauer cites Boogie and Dingo’s Big Saturday Show as a “stand-out example”, a Scotland-wide show “which has increased audience on every station it is broadcast on”.

Bauer says that rather than being a strategy to reduce costs, networking is done to “drive a bigger audience by having bigger talent that engages better than a series of less experienced and engaging talent. It is not one size fits all”.

The networking of Boogie and Dingo might therefore suggest there isn’t new Scottish talent capable of filling the slot. Bauer’s counter-argument is succinct: “If the audiences did not like the output then they would stop listening.”

Global Radio didn’t return calls after my questions on the homogenisation of output were posed. However, Adam Findlay believes radio is always changing, always formatting. “I think radio output is cyclical,” he says. “And yes, audiences will be fed up with stations playing the same music. They will want the individuality they got from their local presenters.”

Meanwhile, Kevin Cameron is prepared to put his money where his local mouth is by going global. Cameron is set to launch GO (Glasgow’s Own) Radio on DAB and he’s already signed up former Clyde presenters Tim Stevens and Suzie McGuire and Scot FM shock-jock Scottie McClue. “All the presenters will be local, the ethos of the station will be local. And we’re confident this is the model of the future,” he says.

What of the future of independent local radio? Radio analyst Tony Stoller, who wrote the compendium Sounds of Your Life, is concerned. “Commercial radio nowadays has all but abandoned genuine localness, leaving that field to the new phenomenon of community radio,” he argues. “But it has still to demonstrate a convincing new distinctiveness. History suggests that, until it does, its struggles may continue.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article