NEXT SATURDAY, May 7, 2016 should be heralding the 25th anniversary of the opening of The Arches under Central Station, Glasgow. Alas, this space which began life damp and derelict and grew into an international arts venue with a unique business plan for experimental performance and clubbing is no more. Maybe longevity was never part of the plan for such a hedonistic citadel of mayhem.

Certainly, when I persuaded British Rail to lend me the keys back in 1991 it was only so that I and some theatre colleagues could present a three-week programme for Glasgow’s long forgotten festival Mayfest – we’d be like one of Edinburgh’s “pop up” style summer fringe venues. The landlords were happy for us to be in short term residence and have the lights on while they showed prospective commercial tenants around. Glasgow Council likewise agreed to lend us some technical gear from the Tramway (which we never returned), and a local publican provided his license so that we could serve interval drinks.

However, when our hard fought for theatre licence arrived it was not for the three weeks we had applied for but for 12 months. We had a great Mayfest. Audiences arrived on the basis of our cheap posters stuck in a few shop windows – no social networking then – and we won the Herald Spirit of Mayfest Award, accompanied by a life-saving cheque for £500. With our new licence proudly on the wall we decided to see how long we could keep going. We had no money and we expected a commercial tenant to replace us at any moment, but as long as we had a theatre space we would continue to stage shows.

Two things changed everything. One was an agreement with a now defunct economic body, Glasgow Development Agency, to pay the rent for six months to British Rail to give us time to organise ourselves into a coherent cultural enterprise. And secondly, alongside our then profit share theatre productions, we decided to start weekend late night clubs. Serious DJs moved over from the Sub Club to run SLAM on Friday nights and we clumsily invented our own theatrical Saturday alternative to house club culture, Cafe Loco, a mixture of performance art, cabaret, disco classics, and house music. All this took place in the bottom part of the building accessed from a very dingy and foul smelling Midland Street. The majority of the arches we left abandoned, apart from the odd temporary exhibition – Alien Wars, Iron Bru Pop Video exhibition, and Dinosaurs Alive! Not to mention Wet Wet Wet occasionally renting the derelict spaces to set up their stage to rehearse their next tour. For weeks at a time Love Is All Around would seep through the walls in the way that music is used as a form of torture.

The combination of all these events meant that we could start to pay ourselves and our artists modest wages. A charitable limited company was established and we were in business – we became the leaseholders.

For years, however, it was a hand to mouth existence. Funding awards started to trickle in from Glasgow Council and Scottish Arts Council but the bulk of revenue was the bar income from the club nights. To run the clubs we needed a late night licence and it took years to get beyond temporary applications. We were living literally from week to week. On one occasion, a Friday at 4pm, we were informed that the licence for the weekend had been denied since we didn’t have a wooden dance floor and stone was deemed too dangerous. We contacted an official and it was agreed that if we could lay a floor that night, the licence would be issued. By 5pm we had found a timber yard willing to supply the necessary sheets and batons to cover 100 square meters of floor space. A few hours later the timber arrived and I managed to recruit an actor friend who was a time-served joiner, and the floor laying began. As each sheet was hammered down to the hastily assembled baton framework, we were painting the surface in black emulsion. By 11pm, with several hundred clubbers queuing outside, the Building Control officers arrived and agreed that we could go ahead. The doors were opened and the night began. Most of the paint was still wet and stuck to dancers’ shoes, but nobody cared.

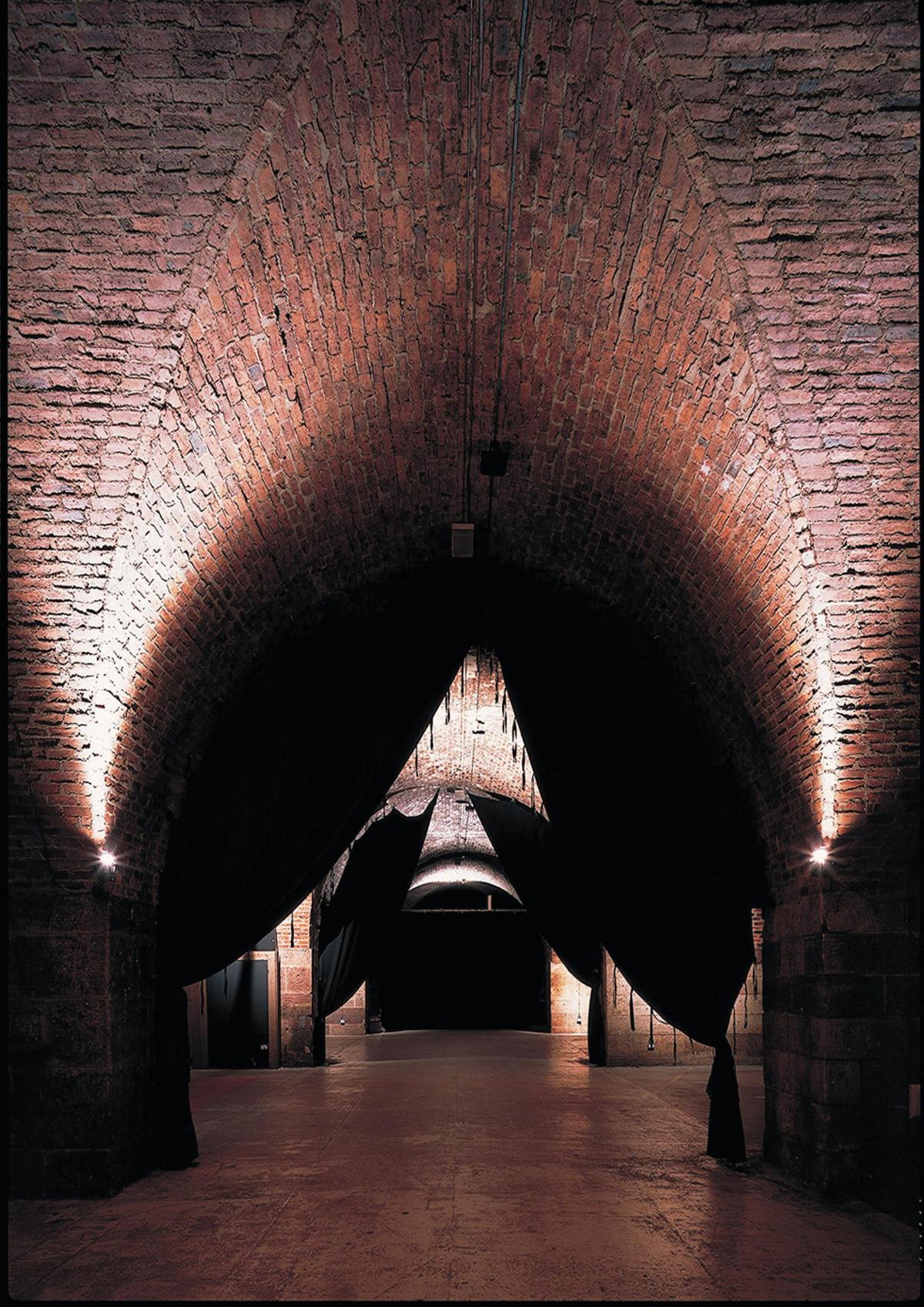

After several years of applications – all inexplicably refused by Glasgow Licensing Board – we were eventually granted a late night licence covering the whole building, with a capacity of 1800 people. It was liberating to stage theatre shows in these derelict spaces and early work included The Crucible with the audience seated on church pews and the actors wading through mud, The Devils in the very dark and damp back arches, and Metropolis -– The Theatre Cut -– a promenade production where a cast of 100 performers re-enacted Fritz Lang’s classic movie. Most importantly from a business standpoint was the expansion of club nights into this vast new arena. We opened with the iconic Liverpool club Cream and, since we had no advanced booking system, 5000 people turned up on that first night, with the majority being turned away. Inside Out, Colours, and Pressure became our own super-clubs and soon the Arches was being known as a night club rather than a theatre. That didn’t bother me as long as the bills were paid and I could create the work I wanted to. The culture of clubbing and theatre collided at times, but fused on many occasions with extraordinary results.

The building was cold and damp throughout most of the first 10 years, resulting in annual chest infections for many of us, and we might have given up the ghost had it not been for the launch of the Arts Lottery Capital funding program which transformed so many venues during the late nineties into more habitable spaces. The Arches project, which took two years to apply for and two more to execute, resulted in a new entrance onto Argyle Street, a basement cafe bar and rehearsal spaces, and a heating and ventilation system which meant that for the first time in the life of that building it became dry and warm.

From then on, the arts programme continued to thrive with commercial activity expanding to corporate events and gigs. Personally, I began to tire of the balancing act between the business needs and theatre production. I felt that things should change and be re-invented but around 2008, after nearly 18 years, I was losing the stomach for the fight and when a vacancy appeared at the Tron further along Argyle Street the chance to return to theatre-making was too compelling. It was time to go.

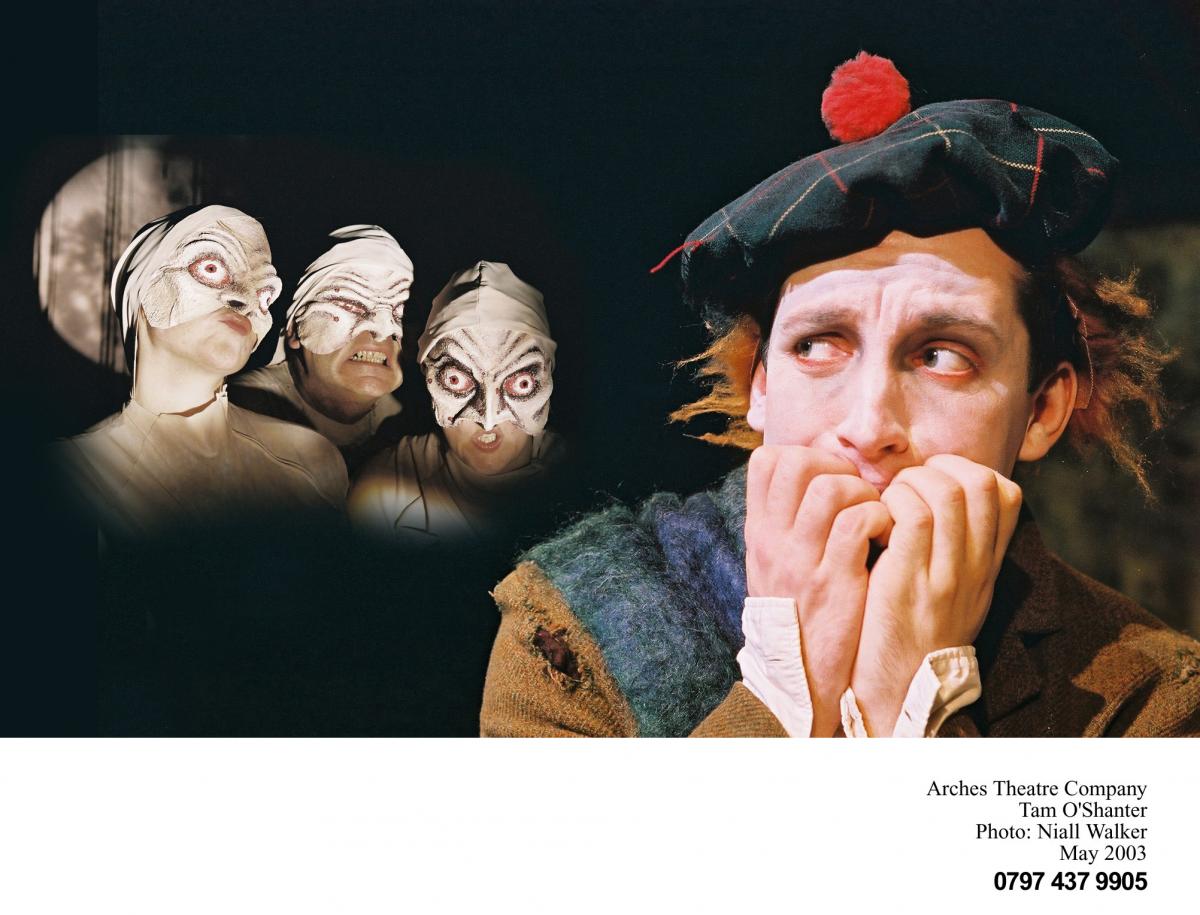

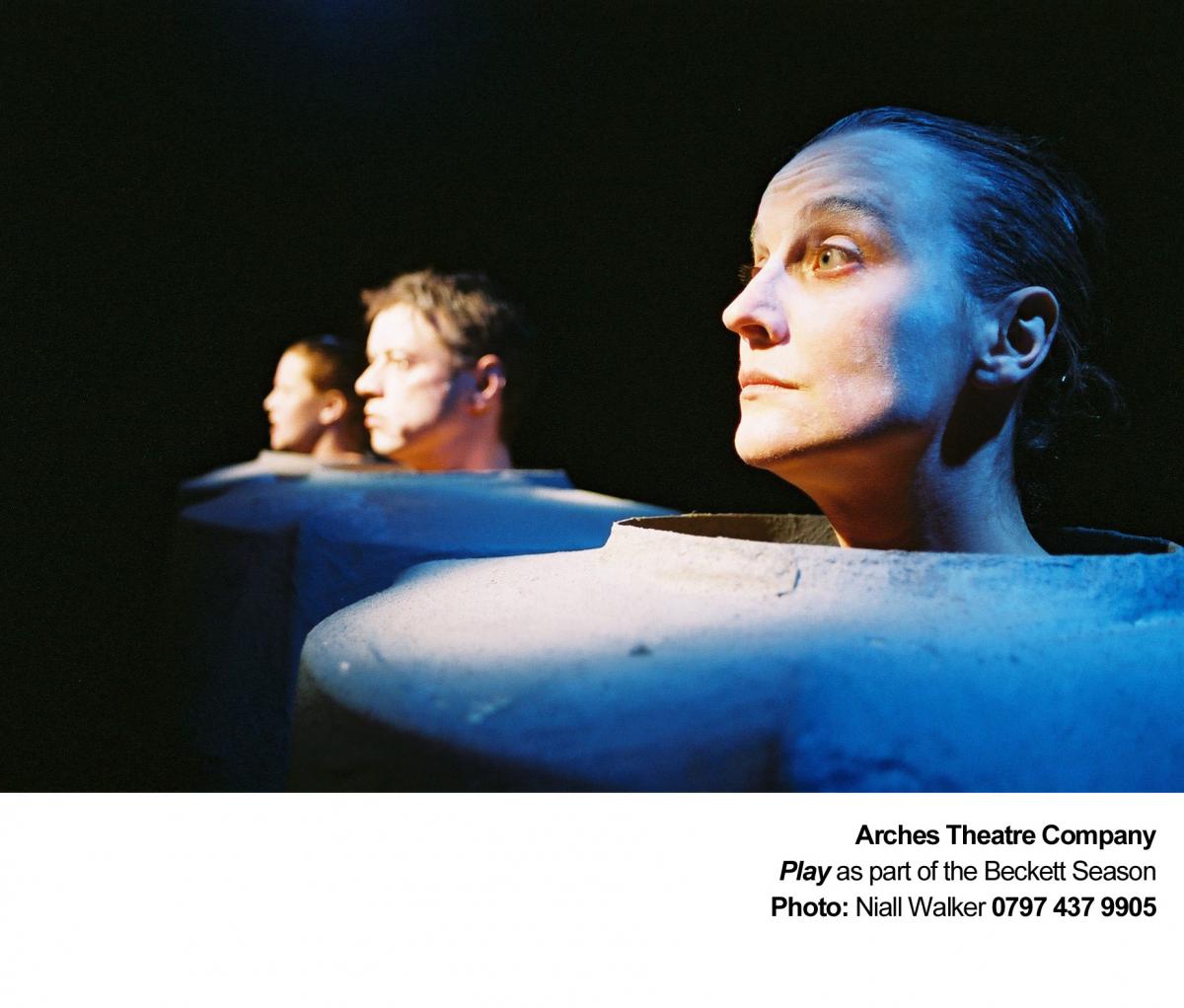

With a new artistic leadership and new energies, the Arches continued to grow in different directions and in a very compelling way – performance works commissioned and generated there began to be toured around the world. It was firmly established as a centre of innovation and an essential bolt hole for young and emergent arts makers who were able to create work inspired by the atmospherics of that extraordinary building. Then last year, as we all know, it shuddered to an abrupt halt.

Much has been written about that demise including conspiracy theories. From my standpoint, late night club management was always a high-risk business. I visited the clubs most weekends throughout my time there and it often scared me to think that our whole operation and the livelihoods of so many people were dependent on such explosions of ecstatic (sic) hedonism. The Arches was the most law abiding and health and safety conscious of any club in Scotland, but over a period of years three young people collapsed and died at Arches club nights and no venue can guarantee sustainability under the shadow of such terrible tragedies.

The loss of The Arches is a poor reflection on the cultural optimism of this city. Time was needed to explore alternative business plans and time wasn’t given. Instead, the administrators, with indecent speed, auctioned off all the equipment and furniture and the place is now dark and silent again – save the rumble of trains up above.

With the power turned off, I can guarantee that the dampness will quickly return, the paint will start to peel and the floorboards will warp and buckle. After all, those cantilevered arches were built to drain the water from the tracks above, and that water, along with the mice and rats, will find ways to seep back into the interior. Before its renovation in 1990, the building had spent 60 years derelict and unused. The landlords will look for another commercial tenant but I think the range of potential uses is surprisingly limited. It might be worth the risk for some homeless theatre makers to ask for the keys so that they can use the place and keep the lights on while prospective commercial tenants are being sought – I’d recommend it.

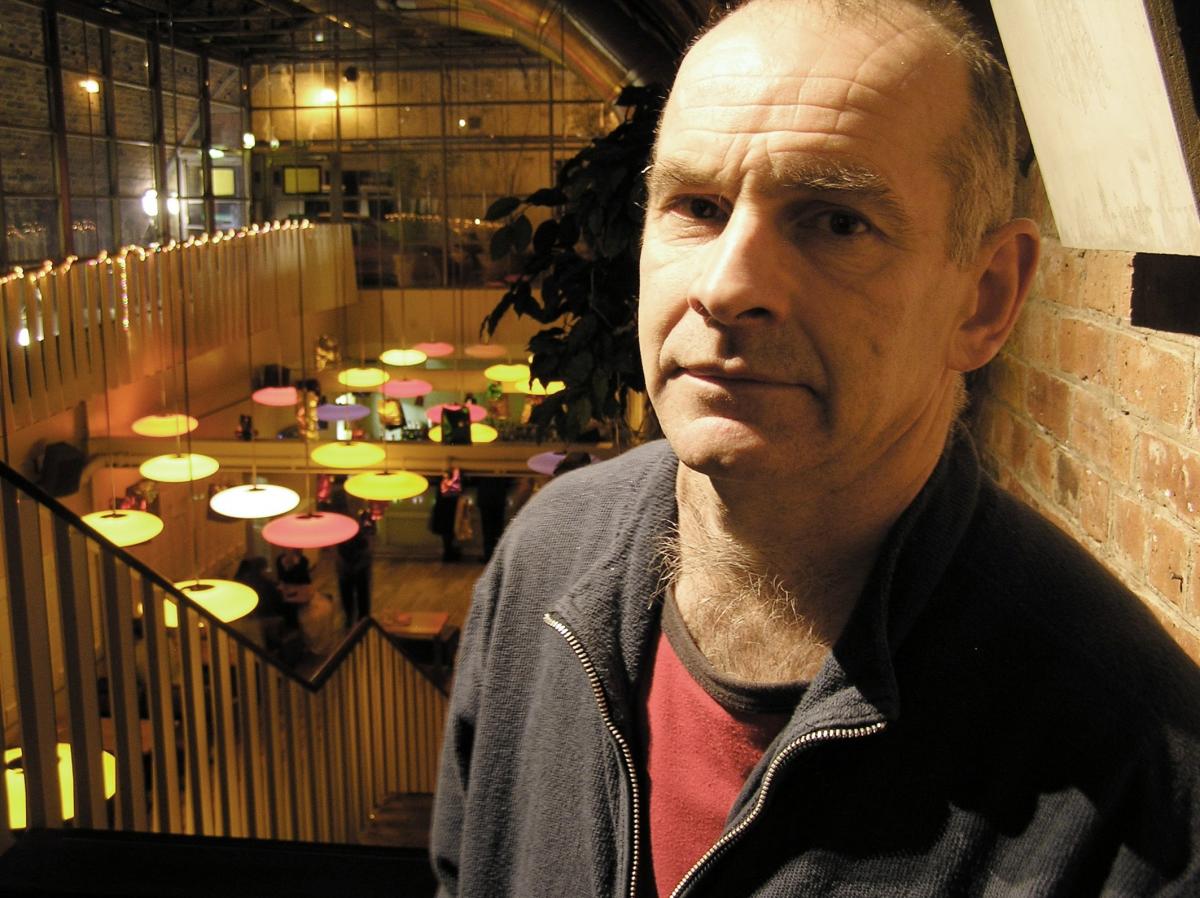

Andy Arnold was founder and artistic director, The Arches, 1991 - 2008

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here