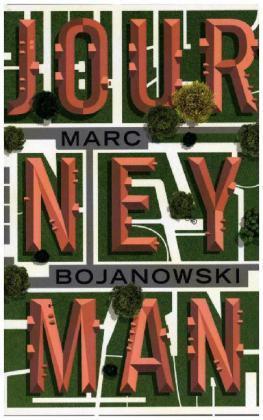

Journeyman

Marc Bojanowski

Granta, £12.99

Review by Alastair Mabbott

As a forest fire rages across the hills surrounding the northern Californian town of Burnridge, a man formerly known as Chance Jackson remarks that the Native Americans used to deliberately set fire to the valley so that the forest would grow back stronger. And fire is definitely the catalyst for growth in this, Marc Bojanowski’s second novel. It carries with it the potential for a new way of life, although precisely what this means is open to interpretation.

Nolan Jackson, a carpenter who has never been able to settle in one place for long, is working on a building site when he sees one of his workmates go up in flames after lighting a cigarette in the presence of flammable chemicals. The accident spurs him to do what he always does when things get difficult: leave town. This time around, he’s abandoning a relationship that has the chance of turning into something lasting, but Nolan can’t stop himself from following the pattern that’s defined his life.

En route to his next port of call, he visits his mother, who makes him promise to drop in on his brother, Chance, who has renamed himself Cosmo, as he’s been in a fragile state since his wife left him. Nolan agrees, but he hasn’t counted on being stranded in Burnridge after his trailer and all his possessions go up in, well, flames. So the brothers are stuck with each other for a while, and for the most part they get along passably well. But Bojanowski puts them under his microscope, studying masculinity not so much in crisis but in stasis.

Yes, it’s a novel about male identity, a subject that was already becoming played-out before we’d even heard of Blair or Britpop. But the author plays his hand well, rooting his story in the singular dynamics of the Jackson family. Nolan and Chance’s father came back from Vietnam with PTSD, but stayed with their mother until his death. Nolan, on the other hand, has distanced himself from his family with his nomadic lifestyle, reinventing himself by adopting a cowboy hat and adding words like “ain’t” and “reckon” to his vocabulary.

Meanwhile, Cosmo has been smoking pot constantly since his wife left him and working obsessively on a book which traces the roots of modern consumer society back to a single battle in the Russo-Japanese War. There are other signs that Cosmo is losing it: he lobs eggs at his troublesome neighbours and scars their lawn with bleach rather than confronting them directly. He also expresses admiration for a fire-raiser who has been busy in Burnridge of late, burning down houses bought by outsiders as holiday homes. We, and Nolan, begin to suspect that the arsonist is Cosmo himself.

While tackling the emotional detachment, obsessiveness and self-destructiveness of his alienated male characters, Bojanowski keeps it simple. There may be a lot going on under the hood, but his direct, unassuming style keeps the reader engaged in the ultimately optimistic story of Nolan’s attempt to overcome the contradictions in his life.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here