TAKE a good look at this picture. It’s a painting of a maze in northern Italy around women being serenaded by a quartet and on the far horizon, hunters on horseback pursue a stag into the woods. In the maze itself, young couples stroll and embrace and kiss and all around the labyrinth there are groups of people picnicking and relaxing and dancing. It is a beautiful and beguiling image of the Renaissance at its glorious height.

But take an even closer look and you will see a hidden message, spelled out in code. Can you see the stag drinking from the river on the far right of the picture? Or the ape ambling along the top of the maze? Take a look too for the dog under the table in the bottom right of the picture or the eagle perched above it in the pergola, and the young couple entering the maze, his arm resting on her waist. All of it is code for the sensory treats on offer in this voluptuous labyrinth, but it is a warning too: you might be tempted to linger here and enjoy yourself, but in the maze of life, there’s a risk of taking the wrong turn and ending up who knows where.

Anyone who saw this picture when it was originally painted by Lodewijk Toeput in the 16th century would have been familiar with all those coded references to the senses and would have recognised straight away that it was an allegory, a story of the senses – stag meant hearing, dog meant smell, ape taste and eagle sight, with the young couple representing touch. Those who saw the picture might also have visited, or certainly heard about, some of the mazes that existed in the great Renaissance gardens including fantastical labyrinths built on rivers, creating the illusion of a puzzle floating on water like a great sailboat.

It is thought the artist Toeput had heard of such places, and may even have visited them, and his great painting, Pleasure Garden With A Maze, was the result. It was one of the earliest paintings to enter the Royal Collection when it was bought by Charles I and is one of 75 on show at Holyroodhouse as part of a new exhibition Painting Paradise: The Art Of The Garden. All of the pictures have been taken from the paintings and other works of art belonging to the royal family, and the aim is to show the many ways in which the garden has been celebrated in art. To that extent, the exhibition is a history lesson, but it is also a celebration of the great achievements of gardening in the last 500 years or so as well as the role of royal and noble patrons who drove the development of gardening. Kings and queens wanted to compete with their rivals and show off to their subjects and their gardens was one way to do it.

The curator of the exhibition is Vanessa Remington, who has chosen a spectacular range of paintings that include some of the earliest and rarest surviving records of gardens and plants. She is particularly fond of the maze painting and says it is an example of how ambitious garden design had become by the 16th century.

“Mazes became a popular feature in the Renaissance garden and Pleasure Garden With A Maze shows a labyrinth in a watery environment. The idea of a water maze sounds a completely fantastical idea, the idea that you could excavate a maze in water, but there really were in the 16th century mazes where you could row around and through the hedges. It was a maze in a moat, which is mindboggling.”

Remington also talks me through the hidden symbols in the painting. “It’s a fantasy painting and an allegory,” she says, “so it’s all about the whole idea of getting trapped in the pleasure of the senses. But the artist could have seen, and certainly would have heard about, mazes like that in existence in northern Italy at the time so he’s drawing on real elements in the Renaissance garden to create this fantasy painting. And who knows, he may well have seen one of the gardens in Italy where labyrinths like this were springing up at this time.”

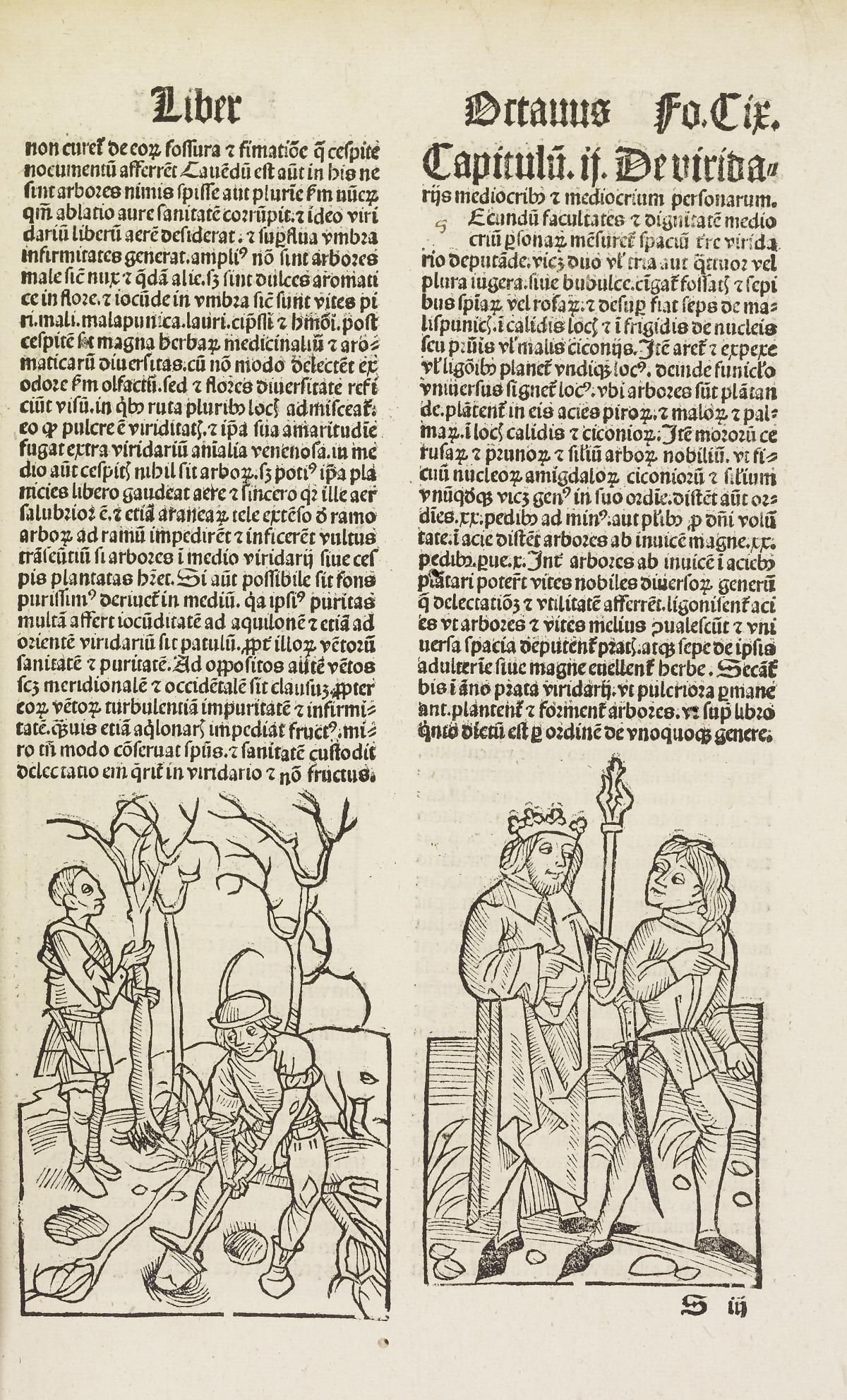

For Remington, the exhibition is a particularly satisfying project as she is a passionate gardener herself. The great range of the Royal Collection, she says, has allowed her to tell the story of the history of the garden, and the garden in art, but there is one object that is particularly important. If you love gardening nowadays, there’s any number of places to turn for advice: Gardener’s World on Radio 4, Monty Don on BBC2 and all kinds of websites. But if you were into gardening 500 years ago, there was only one book to turn to: Ruralia Commoda. It was the first book that set out what gardens should look like, and what plants to use. Beautifully illustrated, one of the chapters was entitled “On making gardens and delightful things skilfully from trees, plants and their fruits”, but there was also advice on making small herb gardens, laying out walks and training willow, elm or birch. If you were looking for the place where gardening began, this might well be it.

What is particularly fascinating about the copy of the book on show at Holyroodhouse is that it was owned by Henry VIII at a time when he was creating his great gardens at his palace at Whitehall and Hampton Court. “It’s the most amazing little volume,” says Remington, “and it’s exciting to be able to have handled it and looked at it, because it’s important on two levels – on a sort of theoretical design level, it was the first work which really set out standards for gardens for the nobility – what they could look like, but also what they could do for them and enhance their status.

“It was thought that any monarch worth his salt ought to have a garden of a particular size and laid out in such a way where he could hold audiences and impress visiting ambassadors and that was the idea that Ruralia Commoda spread.”

Using Ruralia Commoda in this way, Henry VIII was the first British monarch to see the propaganda potential of his gardens and the first recognisable garden in British art is a portrait of Henry and his family painted in 1545. His gardens were intended to be on show for everybody as a way of competing with his rival across the channel, Francis I, the French king who was producing a fabulous Renaissance garden. “Of course Henry is not going to be outdone,” says Remington. “He’s going to keep up. And this is the start of horticultural competition among European monarchs which carries on through the centuries and artists capture this and they become embroiled in the process.”

The monarch who took things to the next level was Louis XIV, who used artists quite deliberately to boast about his gardens at Versailles and his other palace at Marly. Sets of prints were produced which were distributed around Europe and they had a huge impact, with the styles and fashions created by Louis copied across the continent. One of the finest features at Marly were its fountains and water features, although they never quite worked properly and had to be timed to coincide with the king’s progress around the gardens. In paintings, though, the fountains could be shown in all their glory and they caused a sensation across the continent.

One of the paintings in the exhibition, A View Of The Cascade, Bushy Park, shows a water feature created around the same time Louis XIV was making his waves in France. The cascade has recently been renovated and restored and the painting by Marco Ricci was a useful reference in recreating what was there before. Remington says the painting is also a record of one of the great leaps that garden design and innovation took in the 18th century.

“Rerouting water in large volumes was all very ambitious,” she says, “I think that’s one of the things that curating the exhibition has demonstrated for me. We tend to underestimate the scale and ambition of gardeners and designers and what they manage to achieve. And the invention and imagination that went into some of these extraordinary gardens.”

Of course, a lot of money went into the gardens too (and many men died in their construction), which essentially meant you could only create a garden if you were extremely wealthy. Later, though, the idea of the public park emerged and these quickly became places to show off or “parade” – the garden was where polite (and not quite so polite) society gathered to promenade or do business. They could also take refreshments and enjoy concerts and masquerades and by the 18th century, there were more than 60 pleasure gardens of this kind in London.

One of them was St James’s Park, shown in the painting St James’s Park And The Mall, painted around 1745. It’s a highly detailed picture which, like Pleasure Garden With A Maze, features little vignettes of life being lived. There are noblemen strutting in their finery, there are Highland soldiers in close conflab, while in another part of the painting a mother breast-feeds her child. Look out too for the woman (of loose morals?) changing her stockings and the black woman who may be a servant.

“You’ve got an amalgam of society,” says Remington. “You’ve got not only the upper echelons parading in all their finery, you’ve got milkmaids, and soldiers and ne'er-do-wells so you have the whole range of society in a public space all mixing together.”

And then the garden changed again. What had once been a status symbol, an important way for the wealthiest in society to show off how great they were, gradually it became something much smaller and more private, and there are a few paintings in the Royal Collection which show the beginnings of this change – one of Victoria in a cottage on the Balmoral estate and another of her and Prince Albert at Windsor Castle, which was painted by Sir Edwin Landseer.

“We haven’t treated this exhibition as a history of the royal garden,” says Remington, “but the royal garden does play a big role in our story of the art of the garden and where Victoria is concerned, she and Albert treated their gardens in a very different way from previous monarchs. There’s no propaganda element at all, it’s absolutely the opposite – it was a private retreat, a place to relax, to be on their own with their family and it was a much more modern concept of a garden and that was the way that many of their subjects started to treat the garden as well – it wasn’t a functional place any more, it wasn’t for growing food, it was somewhere to relax and spend time.”

Which is pretty much where we still are, 100 years on: the garden as a private place, designed around lawns and shrubs as the Victorians imagined. Not that the garden as royal status symbol has entirely disappeared. This month, Remington will be visiting Dumfries House in Ayrshire, the stately home that Prince Charles helped buy for the nation. Since he did so, he has led a huge and ambitious project to transform the gardens from their relatively rundown state to something more kingly – and in the gift shop, you can buy paintings of the results. Remington says Charles is following in the pattern and fashion of the keen royal gardeners that have gone before him, but in a small way, it is also a reflection that the idea of the garden as a beautiful place but a status symbol too has never really gone away.

Painting Paradise: The Art Of The Garden is at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, until February 26, 2017.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here