Play All: A Bingewatcher’s Notebook

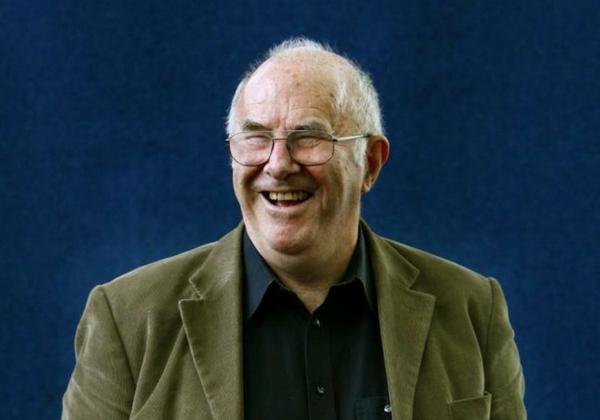

Clive James

Yale University Press £14.99

Reviewed by Alan Taylor

IMAGINE you’ve just received an email from the Grim Reaper telling you it’s time to get your affairs in order and to make your way to the departure lounge. How best to spend your last few, sentient hours? In 2010 Clive James was diagnosed with leukaemia and informed that his days were numbered. His instinctive response was to read and reread, and write. Marooned in a book-lined flat he has been more productive of late than a hyperactive ant. He has completed a translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, a commentary in verse on Proust, a rather wonderful collection of poetry and Last Readings, reflections on the writers and books that have been his constant companions through a life thirled to print.

Now 76, he is still with us and showing no signs that he is about to leap aboard a plane to nowhere. In Play All, sub-titled A Bingewatcher’s Notebook, he turns his gaze on television, of which he was the best critic I have come across. Between 1972 and 1982, his column in the Observer was a plum pudding replete with one-liners that made one gasp at their audacity. My favourite was his description of the ice-skaters Torvill and Dean, dressed in gold costumes, which James likened to two packets of Benson and Hedges cigarettes dancing in a fridge.

Since then television has changed almost beyond recognition, as has the manner in which we consume it. One such development is the box set which allows us to watch programmes as and when we want. Should we so choose we can spend whole days immersed in the likes of House of Cards and Band of Brothers, which some regard as a balm and others as a portent of civilisation’s imminent demise.

Immobilised by illness, James is rapacious in his viewing and makes no excuses for it. “You might ask,” he writes, “how a man who spent his days with the major poems of Browning could spend his evenings with the minor movies of Chow Yun-fat, but I could reply only that it was a duplex need buried deep in my neural network.” Under consideration here are such programmes as Game of Thrones, The Wire, The Sopranos, Mad Men and Battlestar Galactica, several of which I confess I have also watched though not, it would seem, as carefully and as constantly as James.

Why do we allow such shows to swallow up so many of our waking hours? James’s reasoning, his excuse, is simple: they’re gripping. “Without that, complication and sophistication count for nothing, or else you’d actually be enjoying the later novels of Henry James.” The best programmes, he asserts, are like the best novels, intelligent, convincing and engrossing. Moreover, they create worlds which feel real. Apropos The West Wing, he ponders why we find President Barlett “so intensely human”. His answer is that he has “an aching sense of responsibility. He knows he is the best man for the job because he is the best qualified for analysis and decision; but he can’t be at ease in his role, because he knows history too well.”

While there is a tendency in some quarters to derogate television in favour of other art forms, James is rightly impressed by it. His text is awash with references to films and novels, plays and political history. He upbraids Hollywood for its “accursed” rule of casting good-looking women “wherever possible”. Having said that, he is honest enough to admit that while he is “well past the age of misbehaviour” he can still “lose my heart to a pretty face”. He prefers The Wire to Treme, which I do too, but I cannot agree that the making of the latter was “misguided”. On the contrary, it was a brave and often brilliant attempt to portray a city – New Orleans – in the aftermath of disaster.

Likewise, he would rather watch Game of Thrones, of which I had a glut after the first series, than Breaking Bad, whose principal character, the crystal-meth making former teacher Walter White, he found – inexplicable to my mind – “dull”. Nor, it seems, is he terribly impressed by Scandic crime, in particular Wallander, “who has been boring the world for so long now that three different actors have played him if you count Kenneth Branagh”. What are we to infer from that? That Branagh can’t act?

On almost every page of Play All there is an example of splendid, wilful contentiousness and tart observations that hit the bull’s-eye. For example, of Don Draper in Mad Men he says he is “Don Giovanni in a Brooks Brothers shirt”. James is even impressed by The Good Wife, which makes one fear for his sanity. But that is the joy of this book, which makes you want to go back and check that your first impression was correct. Like all the best critics he challenges assumptions and encourages you to think harder about what you’re reading and watching. Whether that’s enough to make you want to dig out old DVDs of Friends and NYPD Blue is of course another matter entirely.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here