THERESA Breslin’s new novel is a tale of teenage cage fighters living in London’s subterranean tunnels. At first sight it appears to be another slice of the dystopia that has dominated fiction for teens and young adults in recent times. In Caged a group of homeless young people seek refuge in the London Underground’s disused tunnels. Led by a former boxer, they attempt to raise money by staging live tournaments which are broadcast on YouTube. The book contains mild sexual tension, violence and grooming, but a British Hunger Games-in-cages it is not. Breslin’s novel is far from dystopian or futuristic. The Carnegie-winner wanted to write something, she says, that was “conceivable”, “that could happen” and that would draw attention to rising teen homelessness, as well as the way young people can so easily slip between the cracks.

Caged, therefore, is set right now. It’s an Oliver Twist for today. “I suppose I didn’t want to create a dystopia because I care about the kids that are currently on the street,” says 68-year-old Breslin. “So I think people have to know it’s not fantasy, it’s not science fiction, it’s not the Hunger Games, which is one step removed.” Although she has written for a range of ages, she has never written a dystopian novel. With the exceptions of retellings of folklore, such as her Illustrated Treasury Of Scottish Folk and Fairy Tales, her books have been rooted in the reality of today or the past, be it the Second World War in Remembrance, 15th-century Spain in Prisoner Of The Inquisition or sectarianism-riven Glasgow in Divided City.

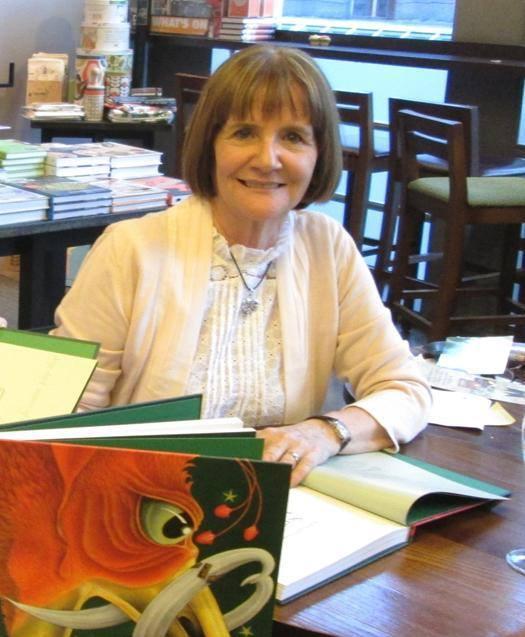

We meet in Glasgow, and conduct our interview partly on a park bench. Behind us a dog breeder is handing over a young Jack Russell pup to its new owner, with blanket, food and training advice. Breslin is distracted by the small drama of a pup being parted from its mother, and wryly chuckles, “There’s a story happening right there.”

She appears fascinated by the workings of the city. Researching her novel she was fascinated by a tour of Glasgow Central Station, with its buried Victorian village beneath, and the Hidden London tours of Underground stations. She is particularly interested in how, “if you pulled the lid off the city you would reveal all the pipes, the cables, the networks, the disused spaces, everything that would be going on under there.”

Breslin, a former school librarian and mother of four grown-up children, has written over 40 books for children. Among her most critically-acclaimed and popular are those written for the same readership as Caged: boys from about 11 years old. Among them is Whispers In The Graveyard, the tale of a 12-year-old boy with dyslexia who becomes obsessed with the victim of a Scottish witch hunt. It won her the Carnegie prize and catapulted her into the big league of children’s fiction. Divided City, meanwhile, is a challenging novel in which sectarianism collides with racism against asylum seekers.

All three books have their action set over the course of the week. The key, she believes, for this age group of boys, is “action and dialogue”. “It sounds really sexist. It isn’t meant to be. This appeals to boys and it also appeals to challenged readers. I wanted to do something that would appeal to the same readership as Whispers and Divided City.” They also share a particular style and sentence structure, designed to maintain narrative drive and keep children reading. “It’s sort of the way that Roald Dahl wrote,” she says, “and the way that Enid Blyton wrote, which is subject, verb, object.”

At the same time she is keen “not to compromise on the language”. This means assuming that children “can cope with words that they don’t know or that they’re not familiar with, so long as the story is there.” The story, therefore, is all-important. That is what drives them on, allowing them to skate over a word, for instance like “grotesque” as they hurry on, eager to find out what happens next.

“It’s also about hard editing,” she adds. “You go back and think is that boring me? Are you just drivelling on too much?” Frequently, she gets children and young people to read the books and deliver their criticisms. “They’re ruthless. I had one boy who came back to me on something I’d written, saying, ‘See your ending? I could have written it better myself.’”

She remains an evangelical advocate of libraries. Currently president of the Chartered Institute of Librarians and Information Professionals in Scotland, she is involved in a campaign against the axing, by Argyll and Bute local authority, of every school librarian post. “Pupils have emailed me saying they are devastated. These librarians had done things like take whole classes down to the Edinburgh Book Festival.”

One of a family of six siblings, she was an avid user of libraries growing up in Kirkintilloch, and over the summer holidays she would be there every day. She describes the fearsome local librarian as “the dragon lady”.

As a youngster, she says, she was like Elinor Brent-Dyer’s princess from her Chalet School books, always waiting to be taken away by her “real” imaginary parents. Though, she notes, “My parents were great. My father was a school janitor and my mum was at home, doing great cooking, raising the six of us, five girls and one boy.”

The violence in Caged is pitched almost perfectly for this early teen market. It’s brutal enough for the reader to wonder if Breslin may be about to take it too far for a young audience, but then she stops short. As part of her research she spoke to a boxer who described “how you could be hugging the person and they could be your best friend, but once you get into the ring you want to kill them.”

The cage-fighting is partly a vehicle for the central story, about homelessness and grooming. She believes that children “are very vulnerable”, and that there “are more and more young people on the street”. This is supported by research. A study by Cambridge University last year showed that more than one in seven young people had slept rough and that “worryingly high levels” of them were using homelessness services. The vast majority of these, it noted, were not captured in official figures.

Fiction writers, she notes, have often been key in pushing for the recognition of the social problems that afflict the young. It was Charles Dickens who influenced the setting up of Dr Barnardo’s homes, and Charles Kingsley, author of The Water Babies, a tale of the plight of chimney sweep boys, who raised public awareness of the plight of these children. As a result, the Chimney Sweep Act was passed in 1840. The issues may not be the same, but Breslin believes we need to be asking questions about how many young people are ending up homeless.

Perhaps not surprisingly, she brings the issue round to libraries and the job librarians do in encouraging young people to read. “It’s why I’m such a passionate advocate for them – because if you look at the illiteracy rates in young offenders’ institutes it is astonishingly high. It’s a huge, huge thing.”

Theresa Breslin will be talking about Caged at Wigtown Book Festival on Friday September 30, and will be appearing with Kate Leiper on October 1.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel