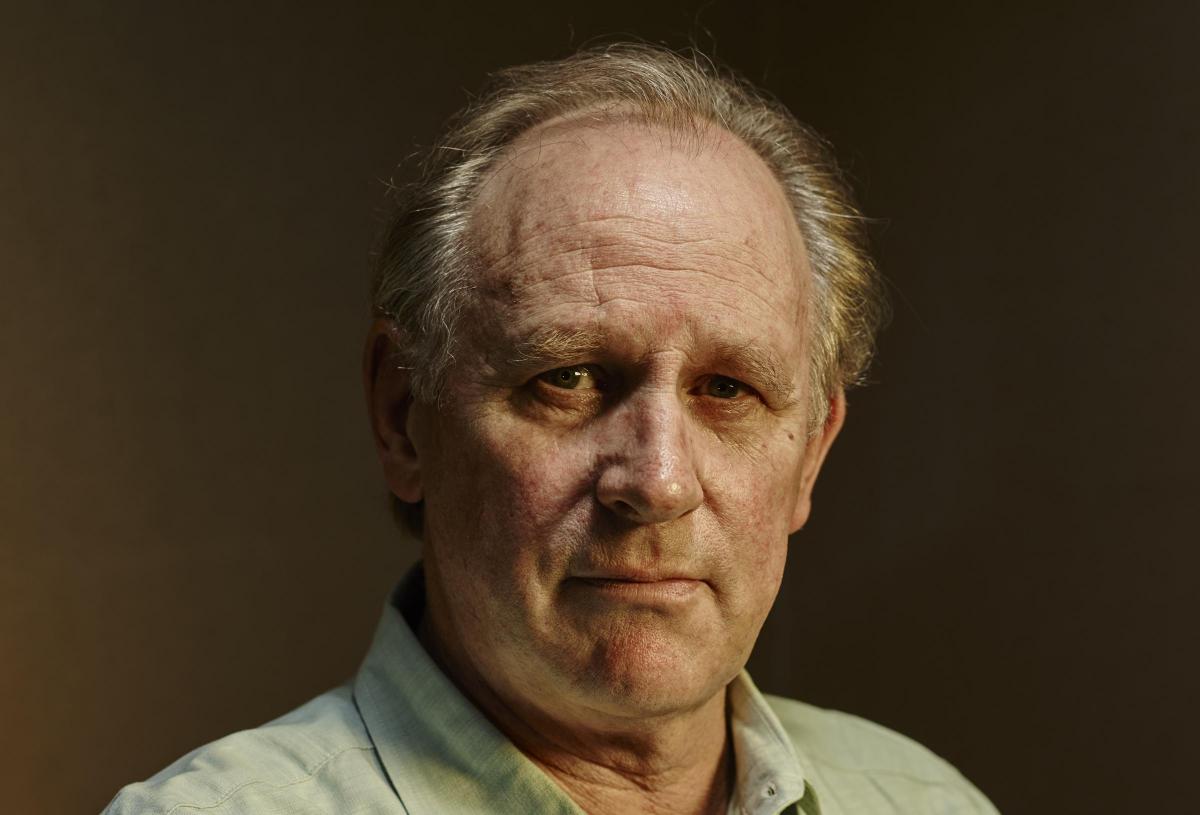

IN July last year, Peter Davison died. The actor and star of Doctor Who and All Creatures Great and Small didn’t realise he was dead until his son emailed him to tell him he was, and so he went online and sure enough, there it was. Dead. A Facebook tribute page. The lot. Funnily enough, it wasn’t the first time the actor had glimpsed his death – in the 1980s, he remembers getting home one night just in time to see his face at the top of the Nine O’Clock News. “Well,” he thought, “I’m either dead or I’m the new Doctor Who.”

As it turns out, Peter Davison recommends the post-death experience. Last year when the 65-year-old was told about his death, he went online to look at the tributes, of which there were many thousands. It was a celebrity death hoax naturally, but it was rather pleasant, says Davison, like having a wake before you die. “What’s the point,” he asks, “of people saying all those nice things about you if you’re not around to hear them?”

And people do say nice things about Peter Davison, partly because he almost always plays nice people. In the 1970s and 80s, he was Tristan Farnon, the galumphing younger vet in All Creatures Great and Small. Then, in 1981, he took over as the fifth Doctor Who and suddenly a character that was rather colossal, forbidding and middle-aged was friendly, dashing and young. You might also remember Davison in the brilliant A Very Peculiar Practice as the nervous young GP surrounded by a gang of monstrous colleagues. Then there was the dad in At Home with the Braithwaites, the series about an ordinary family who win the lottery, and “Dangerous Davies” in the police drama The Last Detective. All very good, all very likeable.

But for Davison himself, it has been a bit different – darker even. I’m meeting the actor on his home patch of Richmond in Surrey and he tells me he sometimes looks at the old clips of himself as Tristan and can barely believe it’s him. He says Robert Hardy, his co-star on All Creatures, once told him that, to overcome his shyness, he should pretend to be Tristan. So that’s what he did, only for it to become, slowly and without realising it, a serious problem.

The problem was this: Peter Davison was an ordinary, shy, comprehensive school boy from a mixed-race background (his father Claude was from the West Indies, his mother Sheila from England), but on television and increasingly in parts of his real life, he was acting like Tristan: a posh, confident, pale-faced, public school boy. For a while, Davison didn’t notice what was happening and by the time he did realise the truth – that he was actually living as his alter ego – he was in massive debt, his career was heading in the wrong way and his marriage, to the actress Sandra Dickinson, was going wrong. We all pretend to be someone we’re not sometimes, but for Davison it became a suffocating trap. “It was madness,” he says.

Several years on, Davison is happy to talk about it all because he’s in much improved circumstances. His career is bouncing along fine, he’s happily married, he has two young sons, and he’s in the curious situation of being the father-in-law to another Doctor Who – his daughter Georgia Moffett is married to David Tennant. He has also moved back here, to Surrey, where he grew up, and is happily ensconced in an end-of-terrace by the Thames.

Today, he’s meeting me just across the river to talk about his memoir, Is There Life Outside the Box?, and he’s in a friendly and enthusiastic mood. We find a corner of a hotel to chat and he happily attacks each subject as it comes up, hurrying through his sentences like his Doctor used to hurry along corridors. He laughs a lot. And he flips his brainy glasses on and off again, like his Doctor did. But what’s most obvious is how self-deprecating he is, lacking in confidence even. “I don’t think I’ve ever been offered a part where I’ve thought I’m right for this,” he says. “Nearly every part I’ve ever done, I’ve thought I’m completely wrong and I’m going to get found out.”

He certainly felt that way in the 1980s when he was offered the lead in Doctor Who. “It felt like a mad idea to me,” he says. “I grew up with William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton and they were older Doctors, avuncular figures.” He says it took him a long time to feel comfortable. “I’m sure there were many people saying, ‘Oh, he’s nowhere near as good as Tom Baker,’ but I had enough people who came up to me and said, ‘You are fantastic, it’s the first time I’ve really loved Doctor Who,’ and there were enough of those for me to feel bolstered up. Maybe I only stay in a role until I’m confident enough to do it and then I leave.”

The problem, as far as Davison was concerned, was the BBC didn’t care about Doctor Who. “It wasn’t a big budget show. It wasn’t prestigious – it was watched by more people and it was sold to just as many countries, but on the BBC canon, it was down at the bottom – it was a basic, earn-us-money show in order to make more prestigious shows.” It’s very different now of course, although Davison has reservations about the modern version. “It’s almost like Trailer Television sometimes, as if you’re watching an enormously long trailer. They need a bit of the Broadchurch philosophy applied to it – let’s slow it down and enjoy the meandering nature of the story.”

Davison says he has no real regrets about his time in Doctor Who, apart from wishing some of the scripts and directors were better. He has also never felt the need to distance himself from the part, as some of the other men who’ve played the Doctor have. “There is no life after Doctor Who,” he says. “I am still Doctor Who.” He also realises the show was one of the highest peaks of his career in the 1980s, before the dip down into the valley of the 1990s when the good jobs and starring roles started to dry up.

What’s really interesting is that Davison might never have ended up becoming an actor at all. As a teenager growing up in the 1960s, his great passion and escape was songwriting. There was even a point when EMI offered him a contract, but in the end he preferred the idea of acting even though to the young Davison, it seemed like something that was outside his grasp. His teachers didn’t exactly encourage him either – one told him he was a layabout who would amount to nothing; another sought to strangle his ambition before it even got going by saying he should think about a career behind the scenes rather than on the stage.

Davison persisted with his ambition though and won a place at the Central School of Speech and Drama, which is where he developed his talent but also started to become much more aware of issues around race raised by his background. He says his parents must have suffered discrimination at some point, as his mother was blonde and blue-eyed, and his father had a West Indian accent and dark skin, but he doesn’t remember being very aware of it until a fellow student at Central, who was South African, took Peter aside and said: you know, your father wouldn’t be allowed into my country.

Davison also remembers that there was only one black student on his course and, 50 years on, he worries that, rather than getting better, the high fees for drama schools mean they have become even less inclusive and open. He also remembers his teachers at drama school telling him he wouldn’t have a career until his forties, but in fact he worked solidly as soon as he left Central, much of the time in Scotland at the Young Lyceum in Edinburgh.

Read more: Mark Smith meets Peter Davison - the full Q&A

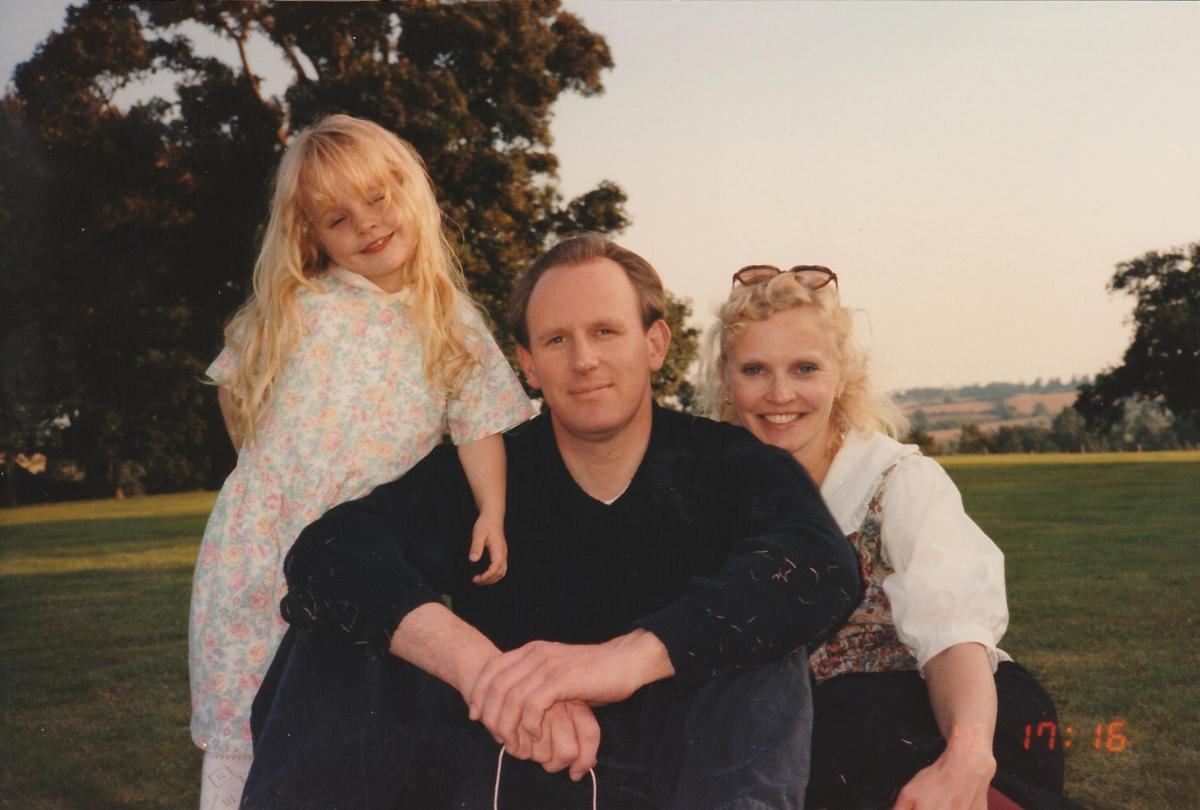

It was at the Lyceum that he met the woman who would become his second wife, Sandra Dickinson. He was already married, to Diane, but began an affair with Dickinson, who was also married. He says regret would be the wrong word for that time in his life, because that would mean regretting Georgia, the daughter he had with Dickinson, but he feels the way he treated Diane was unforgivable. It’s a difficult period to think about for him, because it was the start of a major relationship that went horribly wrong.

Davison sees what happened in his marriage to Dickinson as part of the “Tristan problem”: pretending to be something he wasn’t. For years, he and Dickinson bought bigger and bigger houses, but by 1991 TV series were drying up and there was a stupidly high mortgage and threatening letters from the Inland Revenue asking for £90,000 in back taxes. The couple had been living at the edge of their means for years and suddenly were tipped over it, which only added to the pressure on the disintegrating relationship.

“I very much felt, when I became unhappy in the marriage, I remember thinking that there were too many versions of me. I would go away filming and I felt ‘I’m not really being me’ – in fact, that was me. There was a person in the set-up that I’d got locked into where I was sort of affluent in the public eye, a married TV couple. I felt that I was putting on a fake thing, but I didn’t quite realise that. By that time, I was unhappy in the marriage and it was all going horribly wrong. So when I suddenly ended up on my own I was thinking, ‘Wow; I don’t have to ring up and say I’ll be five minutes late,' or whatever. You weren’t responsible to anybody.”

Davison thinks the period in the 1990s when his career dipped happened because producers got a bit sick of him. "I had gone from job to job to job until we finished All Creatures in 1989 and I think probably parts came in and they would say, ‘What about Peter Davison?’ and they went, ‘No, we see him in everything.' There’s no doubt I went slightly out of fashion.”

Davison also had a large amount of debt, which came exactly at the time his career took a dip. “In one respect there was a constant nagging worry about this debt and my bank manager, who was very supportive because I was vastly in debt, would call me and say, ‘What are we going to do about this? How are you going to pay this back?’ I was trying to avoid the intermediate stage where you’re basically insolvent so it was touch and go whether I should do that. So I tried to pay a little bit back. I was doing OK and I was doing theatre more.”

Was he depressed then? “No, there were moments when I was anxious and I was on my own, which was a weird feeling, but I was doing plays where I was just an ordinary member of the company, I did a play in the West End, I had a really nice time and I think it was when I discovered more about me, especially after the marriage break-up. And I met Elizabeth and we had a baby and then magically, as if it was meant to happen, things started rolling again.”

And they are still rolling along pretty nicely. There was a great little short film written by Davison to celebrate Doctor Who’s 50th anniversary and later this year, he will be making a comedy film with his son-in-law and the father of three of his grandchildren, David Tennant. I ask him how weird it was when Tennant started going out with his daughter and suddenly there were two Doctors in the family and he laughs and says, in fact, it was him who pushed them together when Georgia failed to pick up the hints that David was interested. “David’s a charming man,” he says, “so I suppose in a way I’m a bit more intimidated by him.”

That might sound like Davison just trying to be nice, but in his case, it’s likely to be true. For three years, he played television’s greatest hero but he’s not like some of the other Doctors – he doesn’t have an ego the size of a planet; he’s self-conscious and self-deprecating, the shy boy who pretended to be someone else before finding his true self. He says he sometimes longs to go back, to travel in time like he did on television in the 1980s, and ask his younger self what he was thinking, why he seemed to be free from ambition, why he didn’t think about what comes next. But now he isn’t so hard on himself: he has a good career and he doesn’t mind that he hasn’t done more “serious” work; he sees himself as luckier than most. He accepts, fatalistically, that he is a fatalist. He is happy with who he is.

Is There Life Outside the Box? An Actor Despairs is published by John Blake Publishing priced £20.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here