I Am Not Your Negro (12A)

Five stars

Dir: Raoul Peck

Runtime: 94 minutes

OF the five films in the running for the best documentary Oscar this year, three were about race and racism in America, confirming that far from being a shame from the past, the subject is as fresh as the dawn.

If it had not been for Ezra Edelman’s OJ: Made in America, an epic (seven hours-plus) dig into the media-proclaimed “trial of the century”, my money would have been on Raoul Peck’s outstanding I Am Not Your Negro to lift the Academy Award.

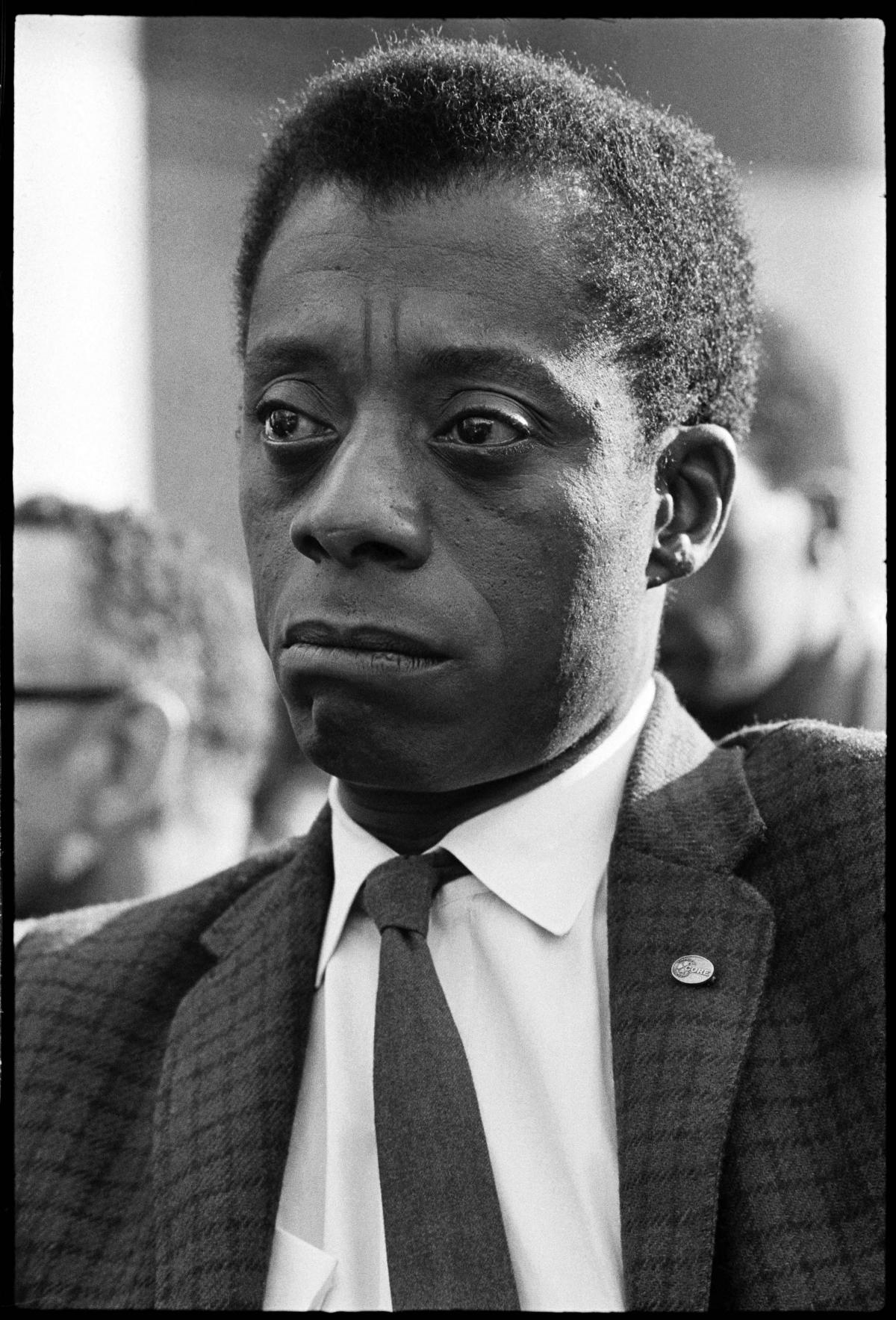

An immersion into the words of James Baldwin as he considers the lives of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X, Peck’s film might be seen as a piece belonging to a particular place and era. Baldwin, after all, passed away in 1987 in his adopted homeland of France, long before Rodney King, OJ, and Black Lives Matter. Yet by the simple act of giving free reign to Baldwin’s eloquence on and off the page, Peck shows him to be a giant for this time as much as his own.

The film’s starting point is a proposal Baldwin sent to his literary agent in 1979. His pitch: to tell the story of America through the lives of his three murdered friends. To these stories he adds details of his own life. So we hear Baldwin tell of his Paris years, and the moment he felt compelled, as news arrived from home of the intensifying struggle, to come back to America and pay his “dues”. We hear of the effect an inspirational teacher, a young white woman, “Bill” Miller, had on the young Baldwin, of life in the Harlem of old, and of his trips to the south to bear witness to what was going on and report back, often in the pages of The New Yorker.

Baldwin only wrote 30 pages of notes for his proposed book, but to these Peck adds clips from his appearances on talk shows and the lecture circuit. Hard to credit now, but unlike the gabfests of today, which largely exist to allow celebrities to plug their latest book/film/set of saucepans, talk shows once gave mainstream air time to serious discussions about weighty issues. The calibre of the guests, too, was enough to make contemporary bookers weep. One programme has not just Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte discussing civil rights, but sitting beside them are Marlon Brando and Charlton Heston. Baldwin himself was always an electrifying guest. “All your buried corpses now begin to speak,” he tells host Dick Cavett after a typically scorching, but painstakingly polite, denunciation of white America’s treatment of African-Americans.

Though we hear often and at length from Baldwin, there is always plenty happening on screen as he speaks. Besides some magnificent photographs, Peck shows clips from the many films that shaped his early years (Dance Fools Dance), or which illustrate his arguments (They Won’t Forget, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Defiant Ones). Pulling the material together is the voice of Samuel L Jackson. With a natural ear for the rhythm and poetry of Baldwin’s writing, he does a superb job of bringing the notes to life. This is a dialled down Jackson, one who knows that the words are the star here.

And what words they are. At the Glasgow Film Festival in February, where I Am Not Your Negro had its premiere, a falling pin would have sounded like a clanging anchor, so rapt was the audience. From slavery to Hollywood, from an equivocating Bobby Kennedy to the chances of a black man becoming president, from the dumbing down of television to consumer culture, Baldwin is on blistering, take no prisoners, form.

There is no attempt to hide his magnificent rage, and no escaping the truth of what he says. It hardly needs Peck to cut from footage of civil rights protests in Baldwin’s era to Black Lives Matter demos today to make the sorry point that some things have not changed, but when it happens, much like the rest of this film, it takes the breath away. Baldwin mattered then, and matters still.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here