Monday

Little Boy Blue

9pm, STV

On Wednesday 22 August 2007, Mel Jones heard a knocking at her door, and opened it to find a faintly familiar man on the step. Polite but strangely panicked, he introduced himself as a coach with the local boys’ football team her son Rhys played for. He’d had a call, he said. “There’s been a thing’s happened with Rhys.” “What’s happened?” “Well, they’re saying…They’re saying he’s been shot.”

Even though most viewers will know what’s coming, Little Boy Blue, a four-part dramatisation of the murder of Rhys Jones and its subsequent investigation, does a good job of conveying at least something of the fear and incomprehension that followed that knock at the door. Until this point, the programme has been pointedly humdrum: slow, quiet, everyday scenes – Mel (Sinéad Keenan) ironing in the living room, throwaway conversations about work and money and the England game on telly later.

Now, though, there is a frantic surge of action. In one unbroken take, the camera follows at Mel’s shoulder as she runs out and into a car, drives a few streets while making a garbled phonecall to her husband, Steve (Brian F O’Byrne), then throws herself from the vehicle, sprinting desperately into a scene of screaming disorder, where finally she finds her little boy, lying in his own blood.

This long single take is an impressive achievement, a remarkable choreography of the camera, Keenan’s performance, the car and dozens of extras. But it doesn’t call attention to itself, there’s nothing slick. The technical brilliance is put to the service of Mel’s experience. What you get is her numb, knotted sense of confusion and urgency, terrible tension then piercing horror. As that car drives in real time through small houses in soft evening sunshine, you get an idea of how short the journey is: that the killing of this boy took place almost obscenely close to his front door; that the distance from the life you know into a life you never imagined can be no distance at all.

Rhys Jones’s killing shocked the UK a decade ago: the 11-year-old with the cheeky face, shot dead in broad daylight as he cut across a pub carpark after football practice. It was one of those crimes that made the nation stop and wonder, how could this happen? What does it say about us?

These are questions that tend to fade away, never answered. Little Boy Blue won’t provide answers, either, of course, but it does a serious job in asking us to consider them again. The writer, Jeff Pope, has form here. As producer, he has been behind some of the best true-crime dramas on British TV, including Appropriate Adult and the recent The Moorside. The long shot summarises his entire approach here: serious care taken behind the camera – the Jones family and the police on the case were interviewed at length, and approve of the script – all put to the service of presenting circumstances in way that feels real and intimate. There are details here that seem odd and wrong precisely because it seems they are exactly what happened, like a striking moment when a detective threatens to arrest the grieving Mel Jones if she won’t stop holding her dead son.

Little Boy Blue won’t change a thing, but it mounts a nagging memorial. It seems beside the point, but it is also worth seeing for the brilliantly unshowy performance of the always-exceptional Stephen Graham, playing Dave Kelly, the detective leading the murder hunt. He’s the closest we have to a new Bob Hoskins.

Sunday

Line Of Duty

9pm, BBC One

A writer who doesn’t just throw in the kitchen sink, but tries to beat you unconscious with the hot tap while he’s doing it, Crazy Jed Mercurio hasn’t been shy of flinging us shocks this series. But, for the penultimate instalment, he’s shifting into hyperdrive, with an episode that features more chewy twists than a Curly Wurly in a tumble dryer, and is twice as melty. At this rate, it wouldn’t be surprising to learn Keeley Hawes’s appearance in The Durrells on STV at 8pm tonight is part of some mad undercover operation to bring Lindsay Denton back from the dead. And, for any newcomers who don’t know who that is, it might be worth reading over the old Wikipedia episode synopses, as some lingering strands going all the way back to Series One raise their heads tonight. Meanwhile: some new human remains are discovered; Roz Huntley’s wrist is starting to smell; Big Ted Hastings reckons he’s found the AC-12 rat; and, any minute, someone is going to mention Ironside.

Tuesday

Horizon: ADHD & Me With Rory Bremner

11.15pm, BBC Two

As he leaps from one point and one voice to another, there’s always been something speedy and scattershot about Rory Bremner’s routines. But is that just part of being a political comedian trying to keep pace with events? Or is something else going on? Bremner has long suspected he has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve had a really active brain,” he says – in fact, he says it several times, because, in a perfect illustration, he seems unable to stay focused long enough to complete the sentence. In this documentary he investigates what ADHD is and meets a variety of people with the condition, from a screaming five-year-old, to a young woman whose potential career as an England hockey player was derailed by her unpredictability. Meanwhile, he plays guinea pig, submitting to tests to have himself diagnosed, and finally trying the drug known as Ritalin. Nervously popping the pill before going on stage, the question is, will medication kill his performance?

Wednesday

24x36: A Movie About Movie Posters

9pm, Sky Arts

This paean to illustrated movie posters, director Kevin Burke’s documentary isn’t perfect, but it’s a labour of love, and its proud nerd passion comes through. Illustrated posters were the norm from the silent days and had their golden age during the 1950s and 60s, when Saul Bass applied bold, abstract genius to Hitchcock’s Vertigo, and Robert McGinnis gave a suave pop-pulp punch to James Bond movies. The final bow came in the late-1970s and early 1980s, with the now-much-fetishised paintings promoting the likes of Jaws, Apocalypse Now, ET, Blade Runner and The Goonies. But the style died in the 1990s, when studios stopped commissioning artists in favour of Photoshopping around the lead actors’ faces: so-called “floating heads.” Aided by collectors, artists and fans including Gremlins director Joe Dante, Burke gives a potted history of the art form’s rise and fall – and also its partial resurrection, exploring how, inspired by the past, a new wave of artist-fans are now creating their own lucrative retro movie poster designs.

Thursday

The Trip To Spain

10.05pm, Sky Atlantic

The Trip is a classic of the “nothing happens” genre, but it has to be said it can sometimes look like there’s even less happening in this third series than in the previous two, in which first “Steve Coogan” and then “Rob Brydon” both went through crises. Not that I’m complaining. During the opening scene tonight – a moody nightmare about the Spanish Inquisition, with both dressed as monks – I made the mistake of taking a drink, most of which ended up shooting out of my eyes, due to the merciless Marlon Brando impression Brydon maintains throughout. And it just continues to look glorious: travelling from the Cathedral Of Sigüenza to Cuenca, this episode is a minibreak for the brain. Along the way, they discuss civil war, Mick Jagger doing Shakespeare, and the depressing rise of posh actors: “Eddie Redmayne is the sort of name an upper-middle-class girl would give her pony.” Talking of crises, Coogan continues to worry over whether his career is crumbling, and Brydon takes an unexpected call.

Friday

When Albums Ruled The World/

The Joy Of The Single

9pm/ 10.30pm, BBC Four

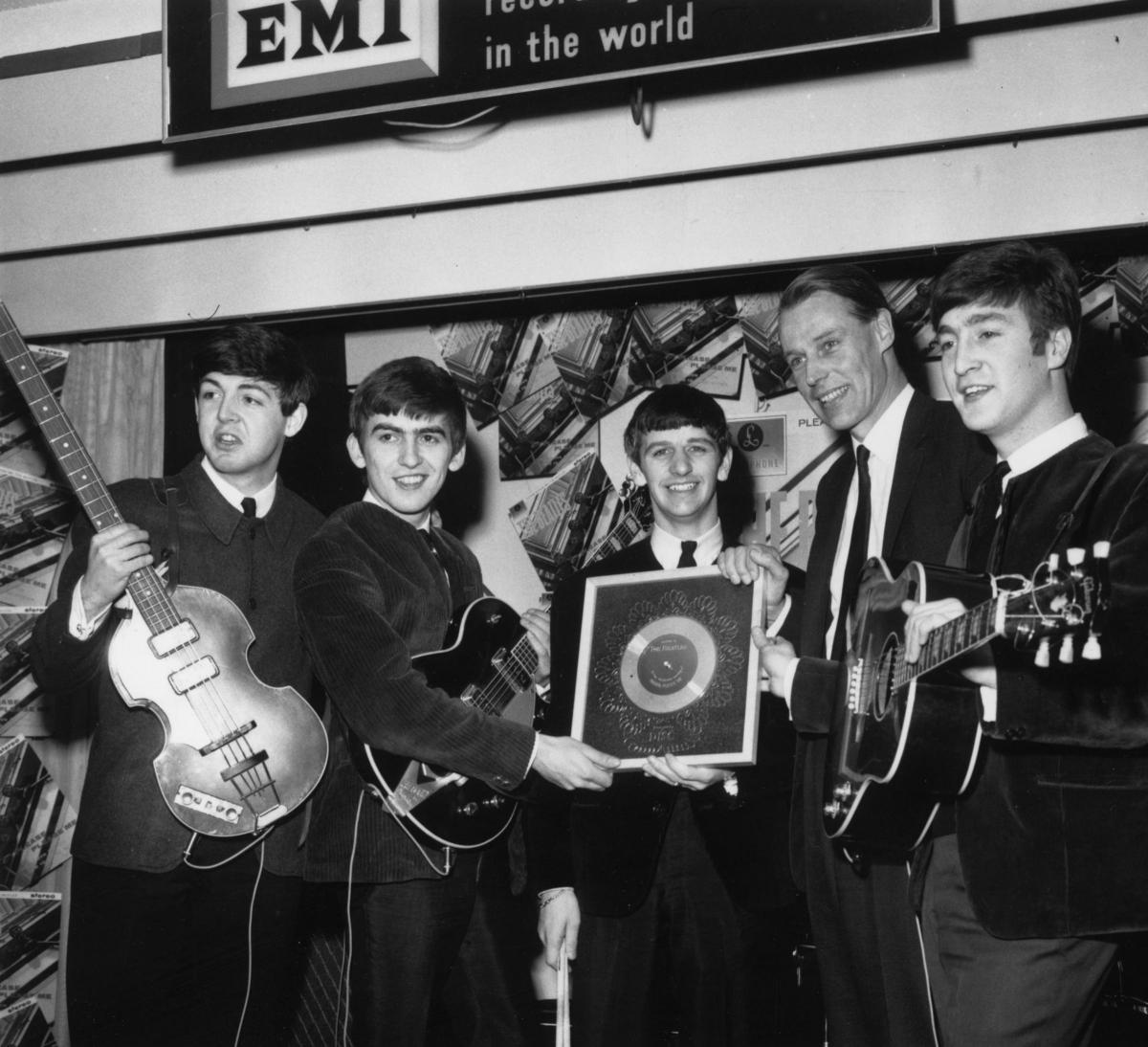

Friday night continues to be repeats night on BBC Four, and this week they’re pulling out two complementary music documentaries – neither, sadly, quite from the top drawer, but both just about painless. First up is a quick ramble through the history of the vinyl LP. Ticking off the usual milestones (Dylan, Beatles, Doors, Floyd, Zep, Pistols, etc), for the most part it will be preaching to the converted, who will still mutter darkly about all the great records being left out. Still, with talking heads including Noel Gallagher, Ray Manzarek, Slash and Grace Slick, it’s a decent enough wallow in warm analogue, as nostalgic pundits breathlessly describe good stuff like how “they had two sides,” and “came in big sleeves.” It’s followed a tribute to the glory of the 7” single, with the likes of Jack White, Noddy Holder, Suzi Quatro, Paul Morley and Richard Hawley among the contributors sharing memories of queuing up at Woolworths, and revealing the most prized possessions in their collections.

Saturday

Doctor Who

7.20pm, BBC One

This week’s episode bears the title “Thin Ice,” although “Treading Water” might be a little nearer the mark. The Tardis has landed The Doctor and Bill in the snowy London of the 1840s. The Thames lies frozen solid, and the last of the great frost fairs is being held on the surface of the river. But, amid all the carnival sideshows and skating, sinister deeds are afoot, and something big is moving just beneath the ice…Maybe the problem here is the uncertain timeslot. The adventure is sweet enough, but it’s the kind of thing that would have turned up as one of the text stories toward the back of a 1960s Dr Who Annual, and perhaps would have been easier to swallow if the programme was going out in the old-fashioned 5:15pm teatime kids show slot. As it is, it heightens the sense that this new series has still really to take off. Bill is great, though, and there’s caddish support from Nicholas “Nathan Barley” Burns.

LAST WEEK...

And so, with one last trip to that nice bench with the cliff behind it, Broadchurch finally ended. The consensus is the third and final series of Chris Chibnall’s crime opera was a marked improvement on the disastrous Series Two. It’s difficult to argue otherwise, if only because it’s difficult to imagine how it could have been any worse.

The more this last run went on, though, the less convinced I was. From the first, Broadchurch was always the most slavish of the Scandi-copy shows, taking the first, best series of The Killing as model. In particular it lifted the Danish hit’s emphasis on focussing as much on a crime’s consequences – how effects, physical and emotional, play out inside individuals, families and communities – as on the solving of the case itself.

Such was the idea, anyway, and in the excellent opening episodes of this last series, it delivered a strong, carefully detailed account of the shock and pain of a woman who had been raped, the sensitive but necessarily clinical work of the police, and the changing shape of her trauma.

This was moving, upsetting and believable. Gradually, though, like the sea nibbling that cliff face, this strong base was incrementally eroded. Partly, the problem was Chibnall’s ostensibly noble attempt to stay loyal to characters from the original series – the Latimer family, whose son Danny was murdered, and who were still going through consequences themselves. But really, this felt increasingly forced. If Broadchurch was so interested in the Latimers, why bring in a new crime? Why feature police at all? Surely, if it’s genuinely what you want to explore, the impact of losing a child to murder would provide enough material for endless hours of drama, without any copshow.

The other problem was the type of copshow Chibnall mounted. Despite the modern problems it held up without saying much about (instant availability of internet pornography is probably having some effect), Broadchurch essentially mounted another Christie-style whodunit, flourishing a teasing parade of suspects and asking us to play guess the villain. Stringing this out meant the writer spending as much time cooking red herrings as wringing his hands over the state of modern man. Lenny Henry gave a good performance, but it was made all the more impressive by the way his character didn’t actually make any sense at all, especially when it came to his tortuously contrived relationship with his detective daughter.

At the same time, though, the way suspicion continually shifted was part of what kept us coming back – when on-demand binging is supposed to have killed off the traditional weekly serial, it’s heartening to see old-fashioned cliff-hangers still working. Similarly, the main reason we kept watching was the oldest in the book: the lead double act, Hardy and Miller, as played by Tennant and Olivia Colman. The writing sometimes let them down, but chemistry never did. They’d have been worth watching if they’d done nothing but microwave teabags together, or sit eating chips on that bench.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here