Men Without Women

Haruki Murakami

Harvill Secker, £16.99

Review by Keith Bruce

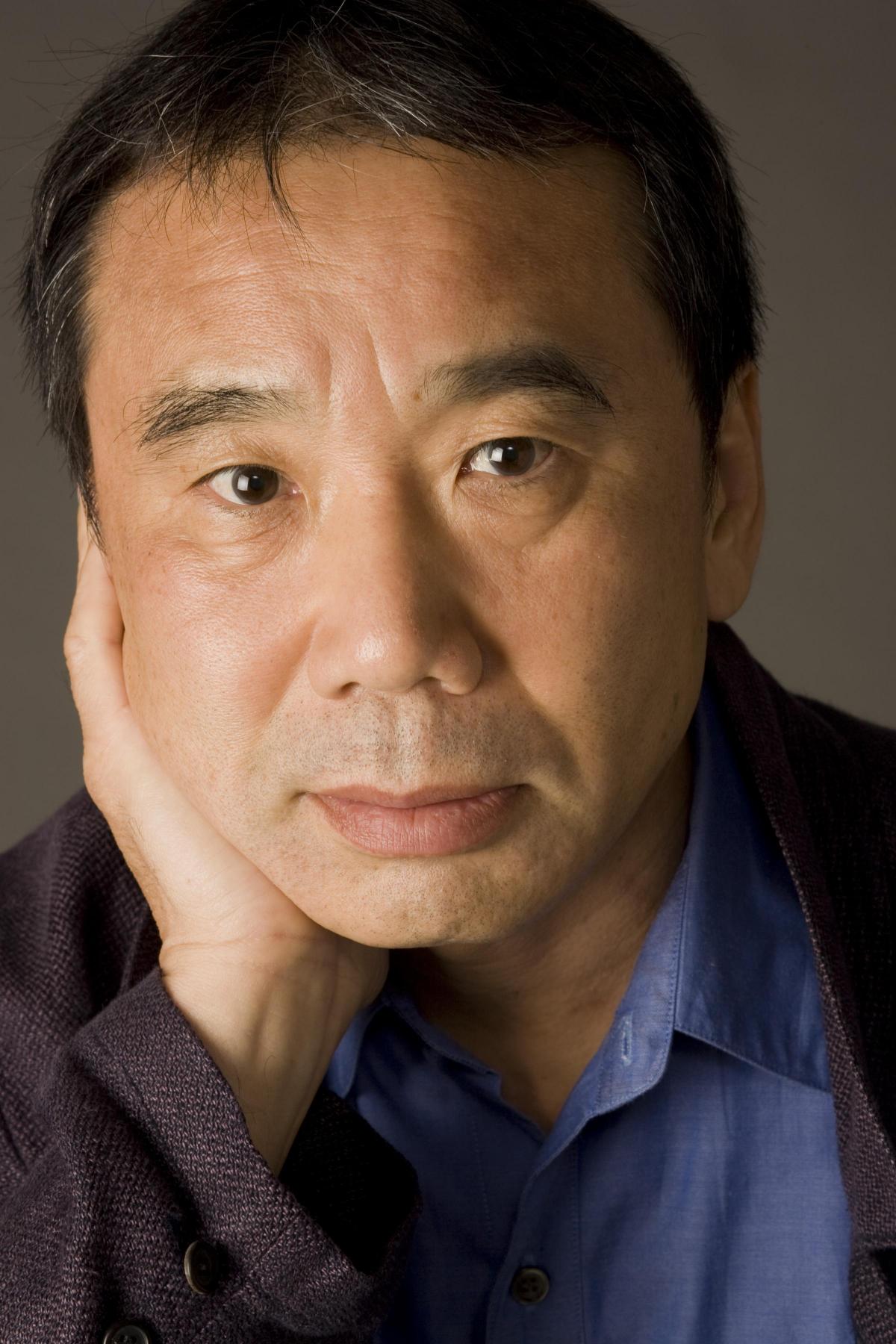

ALTHOUGH he generally fails to act the part in the fashion the Western World finds familiar, Haruki Murakami is Japan's global superstar of literary fiction, with novels from Norwegian Wood, through The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and Kafka on the Shore to IQ84 finding devotees far beyond the islands where his tales are usually explicitly set.

So, a word to those who will be fervently awaiting this new collection of short stories: it is not very new. Published together in Japanese back in 2014, all but two of the seven stories have already appeared in English, four of them in The New Yorker. Not that any of that de-values the collection, and the two originals, An Independent Organ and Men Without Women, are among the best reasons for reading it. The latter (and last in the book) is one of the finest pieces of short-form writing I have enjoyed in many years, and was presumably carefully reserved to give a focus to the work that precedes it.

The title requires some unpacking. It is also the title of Ernest Hemingway's second collection of short stories, which appeared exactly, and very likely not coincidentally, 90 years prior to this book's appearance in English. The macho world of Hemingway could scarcely be further from the jazz bars, urban apartments and sports clubs of Murakami-land, and the American's 1927 Men Without Women are indeed on the front in battle, in the ring, and persuading their current amour that allowing their pregnancy to go full-term is in no-one's best interest.

In Murakami's 2017 collection, the often unfathomable ways of women are the obsession of every male character, and if some of them have departed the scene, others are very much at the centre of the action. In Scheherazade, a man under house arrest (we never learn why) is supplied with more than the groceries by the "woman-who-does", their love-making followed by her telling a sequence of stories that is left as open-ended and mysterious as the reason for his confinement. In a New Yorker interview around the time of the story's first appearance, Murakami conspicuously failed to concur with his inquisitor's suggestion that the collection it was taken from, then just out in Japan, was all about "men who are without – or who lose – women", replying that it was concerned with "isolation, and what it means emotionally." There are female characters in Men Without Women who are every bit as isolated as the men, but usually more by their own choice.

Mostly, however, we see the men and women together, even when that intimacy is explicitly in the past. There is more sex in the 225 pages of these seven stories than I have read in anything else in Murakami's prodigious output. There are plenty of examples elsewhere in his fiction of couples who never quite get it together, while many of the dysfunctional relationships here involve going at it hammer and tongs. In most cases, the man is the grateful supplicant, and in An Independent Organ the Casanova/Don Giovanni-like Dr Tokai suffers in the long run for approaching his own sexual relationships with the contrary attitude. His independence of women for anything more than sex is what dooms him. The opening story, Drive My Car, begins with its subject's misogynistic views on women drivers, only for the female chauffeuse he employs to emerge as a much stronger character than our cuckolded protagonist.

As that title indicates, in other ways we are in familiar Murakami terrain that dates all the way back to 1987's Norwegian Wood. Drive My Car is followed by Yesterday, which does indeed make use of the Paul McCartney song, and in which a young man plays his cards right by selecting "a Woody Allen film set in New York" for a first date. If Scheherazade is an intriguing Russian doll of story-within-story, it nonetheless includes some very Murakami-esque fishy magic realism, while the writer's fascination with Franz Kafka is metamorphosed again in Samsa in Love. The central character of Kino presides over a parade of Murakami memes with an aunt who foresees the Tokyo earthquake and a back street jazz bar with a collection of named discs by Errol Garner and Buddy de Franco played on the original vinyl. This slice of film noir also includes the only character, the efficiently violent Kamita, who might have found a home in Hemingway.

But the reportage that Hemingway masterfully crafted into fiction would struggle to find a toe-hold in the title story. "Only Men Without Women can comprehend how painful, how heartbreaking, it is to become one," muses the pathologically unreliable narrator, whose past love has "probably" disappointed an entire shore leave of randy sailors by taking her own life. He learns of this some indeterminate number of years after her brief experience of his "beautiful" penis, but sees her description memorialised in the Freudian statue of a unicorn that stands in a park "on my usual route".

If the familiar ways of Haruki Murakami are an enthusiasm, there is plenty here to divert the aficionado, but he also takes a turn into riskier territory that could well coax new readers into his distinctive world.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here