The final advance. The company commander Major Lindsay Macduff reads Kipling’s poem If: “Keep your head when all about you are losing theirs.” Prince Charles writes a letter to say the men of the battalion are in his prayers. And on the day itself, Lieutenant William Colquhoun sits in the turret of his tank and plays his bagpipes. The soldiers have been told to expect an ambush, but as they make the final approach on April 3, 2003, thousands of people come out of their houses, waving, smiling and shouting messages of welcome. The people of Basra are pleased to see the Black Watch.

It is not the reaction Scotland’s most famous regiment has always received though. In 1963, President John F Kennedy invited the pipes and drums of the Black Watch to play at the White House, but during the 1971goodwill tour of the US, the soldiers of the Black Watch were heckled and booed. An Irish-American organisation also issued a statement condemning the regiment’s visit in 2006. "The record of the Black Watch in Ireland is one of bloody enforcement of British military rule,” it said. “The history of the Black Watch includes decoration for combat against American citizens during the Revolution for United States independence."

This is what the history of the Black Watch is like. It is celebrated as the oldest Highland regiment (the name is derived from the dark colour of its tartan), it has fought in almost every major conflict of the last 300 years and it is beloved by many (but not all) of the soldiers who have served with it. But the history of the regiment – of any regiment – is made up not just of glories but also defeats and the Black Watch story is much more complicated than the famous red hackle, the flourish of red feathers its soldiers wear in their bonnets. There are darker, more troubling episodes; the men who have served with it have not always behaved as they should; and most of us recall how the story ended – in 2006, when the Black Watch was merged with the remaining Scottish regiments into the Royal Regiment of Scotland. Depending on your point of view, that decision was an acknowledgement that cuts had to be made or a victory for the spineless pen-pushers – either way, it was a bitter and sad exit.

For several years now, the historian Victoria Schofield has been investigating the details of this story and I’m meeting her to talk about the result: her book The Black Watch, Fighting in the Front Line 1899-2006. This is the second volume, following The Highland Furies in 2012 which took us from the regiment’s beginnings in the 18th century as a force to keep the Highlands free of Jacobites up to the late Victorian era.

The new book is the story of the 20th and 21st centuries and the regiment’s fortunes in the First and Second World Wars as well as Korea, the war in Iraq in 2002, the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya, and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. In writing the book, says Schofield, she came to understand human nature through the eyes of a regiment. It’s all there, she says. It’s humanity.

One of the book's most fascinating sections is the one on the First World War and Schofield reminds me there were particular problems for the Black Watch in the trenches. “The uniform worked both ways,” she says. “The kilt meant they were very agile; British soldiers stuck in stiff uniforms were horrified at not being in the kilt. But when you go into this static, muddy warfare, the spats were difficult.”

In other ways, though, the experience of the men of the Black Watch was the same as others. Listen to this Black Watch soldier describing the regiment’s advance over no man’s land. “The bit of line I could see through my glasses suddenly began to fall,” he says, “the falling moving along from right to left. At first I believed they were lying down by order. I did not realise how quickly people could be killed.”

In the end, two-thirds of the 50,000 men commissioned or enlisted into the Black Watch during the First World War were wounded and 8960 were killed. It was a horrific toll, although in the early days of the war many of the men of the Black Watch were just like men in other regiments: eager to get out there and take a shot at the Bosch. Private Tug Wilson said this: “We did not want the war to be over before we got there.”

That sentiment may be hard to understand now, but it is remarkably similar to the feelings of the Black Watch soldiers nearly a century later when they were preparing for deployment in Iraq in 2002. Captain Jamie Riddell says in the book that he was terrified of being left behind and Captain Jules McElhinney felt something similar. The Iraq war, he said, was the ultimate challenge: “Otherwise, it was like training to be a mechanic and never getting to fix a car.” This is one of the trends that Schofield noticed in her research – how in many ways, nothing changes in a regiment even when everything around it is changing.

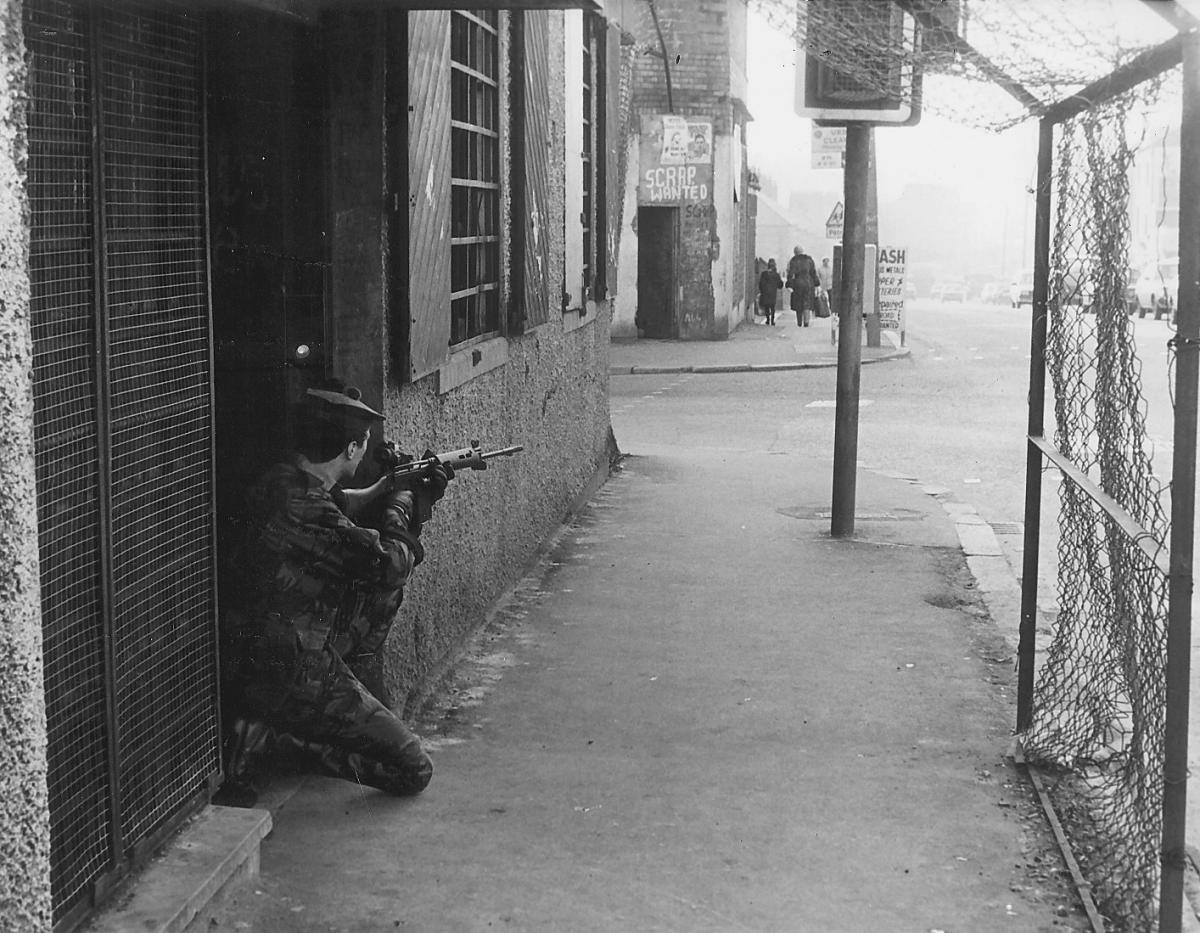

One other factor Schofield takes on in the book are the less celebrated parts of the Black Watch’s history, including the reasons it was booed on those US visits – Northern Ireland. The regiment was deployed to the province 12 times during the Troubles and it was an extraordinary, stressful experience. The men had the nasty feeling of being watched by unseen eyes and rifle sights. Danger was a constant.

“It was going to war, but not to war,” says Schofield, “because they were meant to be peace keeping and in the early days they were totally unprepared for counterinsurgency. What they were used to was ‘we’re going to war, there’s the enemy’ and in a way Northern Ireland is a precursor for Iraq because the enemy is unseen – it was 360-degree warfare. By the end of it, they are pretty well trained for what they’re doing but the army became the target and this is what they weren’t prepared for. Anything could happen and anything did happen.”

The strain also showed in ways that reflected badly on the Black Watch and Schofield says she was clear that such episodes had to be in the book. In one incident in Northern Ireland, five NCOs ransacked a local club and stole cigarettes and alcohol; in another in September 1975, a teenager called Leo Norney was shot dead by Black Watch soldiers in disputed circumstances. Although the patrol had come under fire in west Belfast, there was no proof that Norney had fired the shot and an inquest recorded an open verdict.

Schofield says it was important that incidents such as this were included in her book – indeed, they are a reminder that there is a balance to be struck in military history between idolising soldiers and seeing them in a realistic light. “One can credit the Black Watch with this, they didn’t want a hagiography and every episode that I’ve put in, in an unfavourable light, in a way it’s illustrative that things can go wrong but other stuff has gone right. It would have been wrong to sanitise it and I, as an author, was not prepared to take out, and I had no pressure to take out anything that was negative.”

Another troubling episode included in the book is the regiment’s time in Kenya in the 1950s during the rise of the Mau Mau, the rebel group opposed to British colonial rule. White settlers had been given large swathes of fertile land while the economically deprived Africans were confined to reserves. As law and order deteriorated, the Black Watch was sent in to help keep control. In an operation codenamed Anvil, the British army and the local police rounded up suspected Mau Mau supporters and sent them to detention camps where the conditions were appalling. Allegations of brutality followed.

Schofield says she was unsettled by this period in the regiment’s history. “It is troubling,” she says. “But they were doing what they were ordered to do at a time when the mindset was very different from now.” She also says it is important to make a distinction between the police, the security services and the Black Watch and says that, having spent months going through all the declassified papers, there is no evidence that the regiment was directly involved in brutality

“I think the Black Watch themselves were troubled by it in a way,” she says, “because if you think of pressure on individuals, they had been in Korea, which is under reported, a terrible war, and instead of going home, which they should have done, they were sent to this local difficulty, the Mau Mau insurgency – they recognised that they were being asked yet again.”

It certainly helped the regiment at the time, as it always has, that they had the sense of belonging to a brotherhood, but Schofield notes that not all of the men of the Black Watch have felt that. During the Korean War, for example, the Black Watch was made up predominantly of national servicemen. They were not volunteers and were much less likely to get all watery-eyed about duty, the regiment and king and country.

As for the merger which effectively ended the Black Watch as a regiment, there was a division of opinion on that too. Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Lindsay, a descendent of the regiment’s first colonel, said before it happened that hundreds of years of courage would be wiped out by armchair generals; others were much more pragmatic in the face of cuts ordered by the then Labour Government.

“It did go into two categories,” says Schofield. “Every Scottish regiment fought to try to maintain their separate identities – and in a way they would have been wrong not to do it, just to see, because there was a feeling that it was a lot of pen-pushers down in London. So that was what the old and bold did. But they were retired, they were on their pensions; the younger generation were serving soldiers. One of them said to me, ‘What was I going to do? I wanted to be in the army, we had to make do with whatever happened.’ So the movement was absolutely right, they felt they hadn’t just rolled over and had fought as much as possible but it was clear this was what was going to happen; it wasn’t just exclusively the Scottish regiments that were being merged – others were too. Feelings did run high – and maybe doubly high because all the negotiations and discussions were happening while they were deployed in Iraq.”

Eventually, the merger did go ahead in March 2006, with the regiment reformed as the Black Watch, 3rd Battalion the Royal Regiment of Scotland. Some called that day Black Tuesday, with some wives wearing black to the final parade, but Major General Euan Loudon, colonel of the new Royal Regiment, said change had visited the regiment following a remarkable record of service.

I see a little bit of the record myself when, after my chat with Schofield, I visit the Black Watch Museum in Perth, where the regiment was founded in the 18th century. By the gate there are several memorials to the regiment’s dead from the First and Second World Wars as well as Iraq and Afghanistan. But there is also another memorial that is entirely blank and has no names. The museum left the stone blank when they put it up because at the time they did not know how long the Iraq or Afghanistan campaigns would last and thankfully it was never needed. But its blank face is almost as powerful as the names on the other memorials. It is a reminder that, although the history of the Black Watch as a regiment is over, the bigger story of warfare goes on and it is the same as it ever was: people have died in the past, people are dying now and people will die in the future.

The Black Watch, Fighting in the Front Line 1899-2006 by Victoria Schofield is published by Head of Zeus, priced £40

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here