“THE thing I want to know. Anoushka,” I ask the woman on the other end of the line, "is this. How bloody difficult is it to learn to play the sitar?”

Anoushka Shankar’s laughter glissandos down the scale. “It’s really hard,” she finally says as the ripples of amusement fade from her voice. “Obviously I haven’t played every other instrument to compare it to but people who play other instruments tell me that it’s way harder than other string instruments.”

Well, yes, given that your average sitar is on average 4ft tall, and has somewhere in the region of 20 strings, that doesn’t surprise me.

“It’s just difficult, to start with, to hold the instrument right, to get the positioning right,” Shankar continues. “It’s incredibly painful – the way it cuts into your fingers as you bend the fret. From the beginning it’s very challenging.”

And that’s before you get to the music itself, she adds. Those complex, intricate, immense, ever-shifting ragas.

Ah yes. As Yehudi Menuhin once noted: “It is quite impossible for an idiot to play beautiful Indian music.”

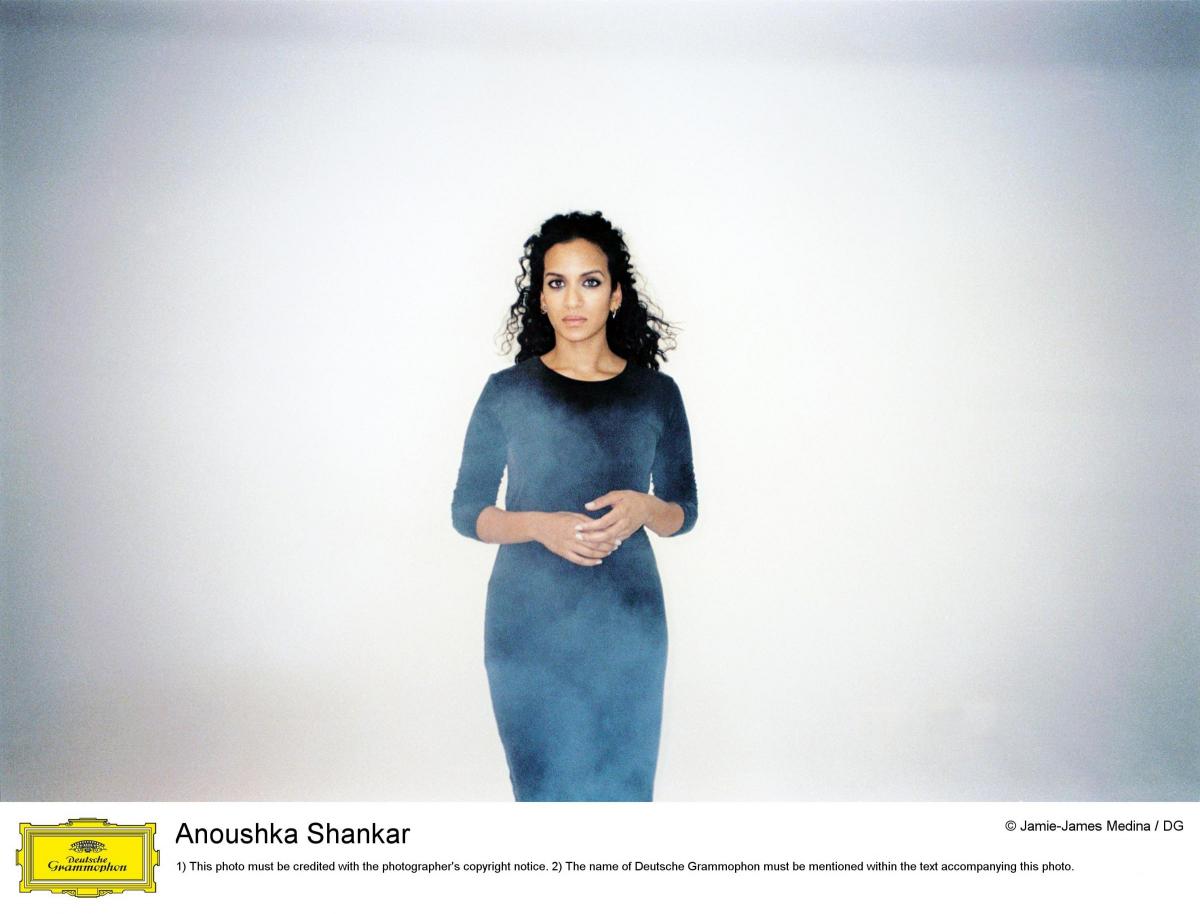

Anoushka Shankar is no idiot. She has been playing the sitar since she was seven years old. These days she is rather good at it.

But perhaps, as her surname might suggest, she started with an inbuilt advantage.

Ravi Shankar – or Dad, as Anoushka is qualified to call him – was the man who introduced the instrument to the West via the Beatles. He taught George Harrison and worked with Menuhin. And, yes, he taught his daughter too.

Since her father’s death, Shankar, 36, is perhaps the most famous sitar player in the world, working the instrument on a number of increasingly adventurous collaborative albums that forge links between Indian music and other world musical traditions.

You can hear that appetite on her most recent album Land Of Gold, which manages to nest her sitar-playing in a sound-bed that takes in electronica, Sri Lankan rapper MIA, the German-Turkish singer Alev Lenz and, um, Vanessa Redgrave. The album is the foundation for her show at this year’s Edinburgh International Festival on Wednesday. (I'm guessing neither Vanessa nor MIA will be in attendance.)

In that sense, Shankar’s work is just as collaborative and outward-looking as her father’s, you might argue. “Yeah, very much so,” she agrees.

What is different, she points out, is that Ravi Shankar was doing it before anyone else. “He was a pioneer, the first person to bring Indian music to the West. So if you analyse his collaborations they were very much in the teacher-student capacity, whether it was with Menuhin or any of the other people or orchestras he wrote compositions for. They are very much Indian music written for Western musicians or instruments.

“Several generations on, it’s more about dialogue and cross-collaboration. In my music, like other artists in my timeframe, it’s a two-way dialogue where I am interested in being the student and sharing my music, but also seeing what my sitar can do. Can my sitar play outside of its genre as well?”

Land Of Gold is proof that it can. It’s also proof that she is not just her father’s daughter. But questions about her father are inevitable. What I want to know, is did she pester her dad for Beatles stories when she was younger?

“Stories were fast and furious in our house," she says. "There were so many historical titbits and funny stories. Not the Beatles. But George was a big part of our lives as I was growing up.”

Ravi Shankar was already a musical superstar when his daughter was born in 1981. He was also 61, had been married and divorced, and had had an affair with a New York music promoter (Sue Jones, mother of the singer Norah).

Anoushka Shankar’s mother Sukanya was a friend. After Anoushka was born, Sukanya was a single parent in London. She and her daughter would perhaps see Ravi twice a year back then. The daughter didn’t even know the musician was her father for the first few years of her life.

And then when Anoushka was seven her parents got married and moved the family to California. That’s where the sitar lessons began. “They made a half-sized sitar for me. I know some kids who start on full-size sitars just not picking them off the ground but that seems a bit crazy to me.”

She explains the learning process as an immersion. The music was all around her anyway. She had been watching her father play concerts since she was a baby.

“I already loved the music, I loved hearing it. And day by day I got better. I experienced more of the pleasure of playing.”

From her early teens she began to play regularly with her father and continued up until his death in 2012. She was in the middle of making her seventh album, Traces Of You, when he died. When she returned to the studio her half-sister Norah joined her to record tracks. Music has always been a family business for Shankar. It remains so today.

These days Shankar lives in London with her husband, the film director Joe Wright, and their two young sons Zubin and Mohan. Wright, best known for directing Pride & Prejudice and Atonement, met Shankar over dinner in Delhi when he was visiting India on research in 2009. They married the following year.

Motherhood changes a musician, Anoushka Shankar reckons. “Unequivocally. I do know some musicians who are very wrapped up in their music and the music feeds itself. That’s where they get their inspiration from. But I’m the kind of person who needs to be in the world. I’m very connected to my life and to people and that’s where I get my inspiration from.

“And so becoming a parent …" She breathes in. “It feels like a big before and after chapter in my life where my music-making has really changed since I had my boys.”

Wright is, readers will be pleased to learn, hands-on in the childcare department. “Joe totally does his share. What’s great is the longer we’re married the more we’re willing to examine things and change them as needed. We’re both on board with everything.”

And motherhood, Shankar says, has also made her a better musician in a way. “Being a parent is now the biggest thing in my life so there’s a lighter touch I have in my music now. It’s my outlet. It’s my fun. It’s my creativity. And that’s actually made me write a lot more easily.”

But parenthood has also seeped into what she wants to write about. In 2015, Anoushka Shankar needed to make a new album. That’s how the business works. But what emerged was about more than just commercial reality.

“I had just had my second son in February and I knew by some time in the autumn I wanted to be working on new music,” she recalls.

“But what happened was, I was kind of in this blissed-out cocoon. I wasn’t really reading the newspapers. I was just home with my family. And then after two or three months of that, in the summer of 2015, I poked my head back out into the world and I was overwhelmed and horrified by the news.”

That was the summer of the mass migrations of refugees to Europe from the Middle East. Every night on the television, footage of frighteningly overcrowded boats full of desperate people filled the screen.

“Having been in a mother-and-child bubble to then see image after image of families just trying to be safe …” Her voice trails off.

She remembers reading a story in one of the tabloids. It wasn’t so much the story itself as the below-the-line comments on the website that horrified her. The inhumanity of the responses.

“The way that people could view other people. The level of disconnect humanity can reach. When you can’t even view a child crying on a boat with compassion any more ... That absolutely broke me.”

All that anger and pain was channelled into her charity work and activism. But it also fuelled her music.

“Basically in the first week I sat with musicians and we were writing music and by the third song we realised that that was what the album was about because there was a story that could be told.”

Land Of Gold was the result. But what is Anoushka Shankar's land? Where are her roots? She lives in London, grew up in the US and has so many ties with India, the land of her father.

They are all part of her make-up, but Shankar does not identify with any particular nationality. “I get frustrated by the limitations it imposes. Look at the disasters we create ourselves based on national identities.

“I think culture can be something that can be really beautiful. So sharing artistic culture has huge benefits. And obviously being who I am and the music I play, you would assume I value that.

“But I don’t value personhood being attached to nationalities. We’re people. We have opinions. We have feelings.

“On social media I can write something [about events in India] and it’s amazing the number of people who go: ‘That’s not India. How do you say that when you’re in England?’

“Why shouldn’t I? That kind of thing is bullsh** to me really. And I think it creates a lot of problems in the world.”

This is Shankar now. A strong, confident woman who has found her voice outwith music and is speaking out more and more.

Never more so than in 2013, when she recorded a video for the One Billion Rising campaign to combat violence against women and children. The video was a response to the horrific rape and murder of 23-year-old student Jyoti Singh on a bus in Delhi in December the previous year.

In the video, Shankar revealed that as a child she had been the victim of sexual abuse herself. Her parents had known and trusted the man who abused her.

She wasn’t really ready for the reaction to the video when it went viral. Having to talk about what had happened for the next year felt raw, she admits.

But she also found a liberation in speaking out. “I think that’s because I did it for the right reason, as part of feeling like there needed to be more awareness of how sexual violence affects everyone, particularly in India.

“I think my motives were right, so I didn’t feel I had just done a tell-all. There was something about being able to let go a secret that I’d carried for so long.”

It also countered the idea that, given her background, someone as privileged as her should not have a voice at all.

In the media, Shankar says, she could sometimes be portrayed as a princess. “The angle was very much: ‘Silver spoon. Nothing bad’s ever happened to her. She’s been given this career platform and it’s all great.’ It was always very frustrating to be told I’d had a perfect life when people never had a clue.”

We’ve come a long way from the difficulty of playing the sitar, haven’t we? When she looks around, I ask her, can she see any hope in the world? Or is there nothing but despair?

“June 24 last year [the day after the EU referendum], I felt despair. November after the American election I felt despair. But you keep seeing these uprisings. The feminist movement is rising up again among younger people who don’t want their rights taken away from them. You see people getting fired up.”

She cites the British election and the galvanising of the youth vote in the summer. “And then on a cheesy but also true level I look at my own two kids laughing and that helps. There’s beauty to fight for.”

This is a family story. But then, aren’t they all?

Anoushka Shankar’s Land Of Gold is at the Usher Hall on Wednesday (August 16) as part of the Edinburgh International Festival www.eif.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here