Back in the last century the German film director Wim Wenders told a meeting of Japanese architects that film was a city art. “It has come into existence and blossomed together with the great cities of the world, since the end of the 19th century,” he told them.

For Wenders, “the cinema is the mirror of the 20th-century city and 20th-century mankind.”

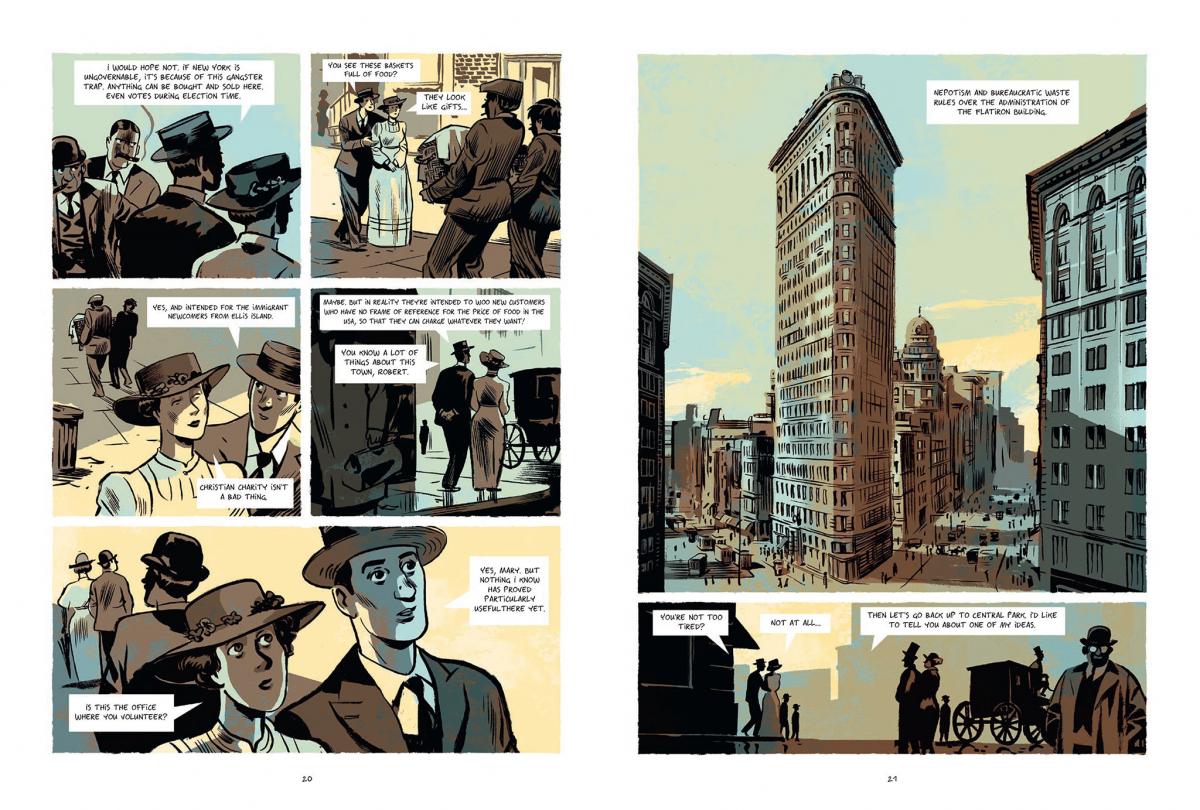

His words came to mind reading Pierre Christin and Olivier Balez’s graphic memoir, Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City the other week, a book that shows just how interesting urban planning is as a subject.

Operating under a raft of different titles (Coordinator of urban construction, director of the committee for the eradications of slums) Moses was the man who did more than anything to shape the city of New York in the 20th century.

Christin and Balez’’s book is an excellent primer on Moses’ overweening ambition and the sometimes callous indifference to the human impact of his monumental schemes. (It’s certainly a much more easily digestible book than Robert A Caro’s 1300-plus page memoir of the unelected city planner.)

Watching New York rise and fall in its pages, though, I remembered the Wenders quote and it struck me that you could just as easily substitute the word comics for cinema in his speech and the meaning would hold good.

We can argue the toss over what the first comic was, but there’s no question the form rose in conjunction with the rise of the city, thanks to the adoption of cheap newsprint and the widening of education. Like cinema then, the comic strip was hothoused in cities.

More than that, you could argue that comics are essentially an urban artform. They are not only the result of urbanisation, they reflect it too. Like cinema, they are a mirror to the metropolis.

Of course, think about it for a second or two and you can think of exceptions. Comic strips like Pogo and Peanuts spring instantly to mind. War comics are set in foxholes, trenches and swampland. And the latter is the setting for Swamp Thing too.

But even Swamp Thing has visited the city in his time. And when we think of comics how many of us immediately think of a Marvel or DC splash page; Batman glowering down on Gotham. Spider-Man swinging through the streets of New York.

You could argue that nearly all superhero comics are predicated on an urban setting. Yes, there are exceptions here too; Superboy in Smallville springs to mind - that 1950s Norman Rockwell reimagining of the Superman mythos. More recently, the early issues of Black Hammer have retreated to the rural.

But even then, Jeff Lemire’s comic likes to scale up to the urban when there is some destruction to be done.

You could go further in fact and suggest that in most superhero comics, the city is central to the narrative. Would Batman even exist if he didn’t live in Gotham? What crimes would he solve? Would he have even realised that “criminals are a superstitious cowardly lot” in the first place if his parents hadn’t been gunned down in a Gotham street?

Discussing 2000AD’s leading strip, the artist D’Israeli has argued that Mega-City One is more important than its chief exponent of law and order. Writing on his blog in 2009, he said: “Really, the city is the actual star of Judge Dredd.

“I mean, Dredd himself is a man of limited attributes and predictable reactions. His value is giving us a fixed point, a window through which to explore the endless fountain of new phenomena that is the Mega-City. It's the Mega-City that powers Judge Dredd, and Judge Dredd that has powered 2000AD for the last 30 years. It's no coincidence that 2000AD's spin-off is called The Megazine.”

Think, too, of Radiant City in Dean Motter’s comic Mr X, Philippe Druillet’s Delirius, a city the size of a planet, Ben Katchor’s visions of old New York in Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer and Paul Madonna’s San Francisco in All Over Coffee. In comic strips the city is so often both setting and subject matter.

Back to Robert Moses. On page 68 of Christin and Balez’s graphic memoir, artist Olivier Balez is illustrating the development of New York’s lower east side. He records the building of the Washington Square Village, Morningside Gardens, Chatham Towers, high-rises which are “crushing the lower east side under their weight.”

Balez draws these three buildings on the same page in three vertical panels. The panels take the shape of the buildings.

Looking at the page I flashed on a memory of Frank Miller and Klaus Janson’s run on Daredevil from the early 1980s, possibly my favourite superhero strip, and Janson’s repeated use of narrow vertical panels to accentuate the sense of scale and danger that was life in Hell’s Kitchen.

The fact is page design is mapped onto urban design time and again in comics. Which means the comic book artist is in his or her own way an architect.

And maybe, just maybe, you could argue the city is itself a comic strip. A three-dimensional, moving version.

Which reminds me of a picture I took in Scotland’s National Museum a while back.

What is it? My own living comic book page.

Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City, is published by Nobrow, priced £12.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here