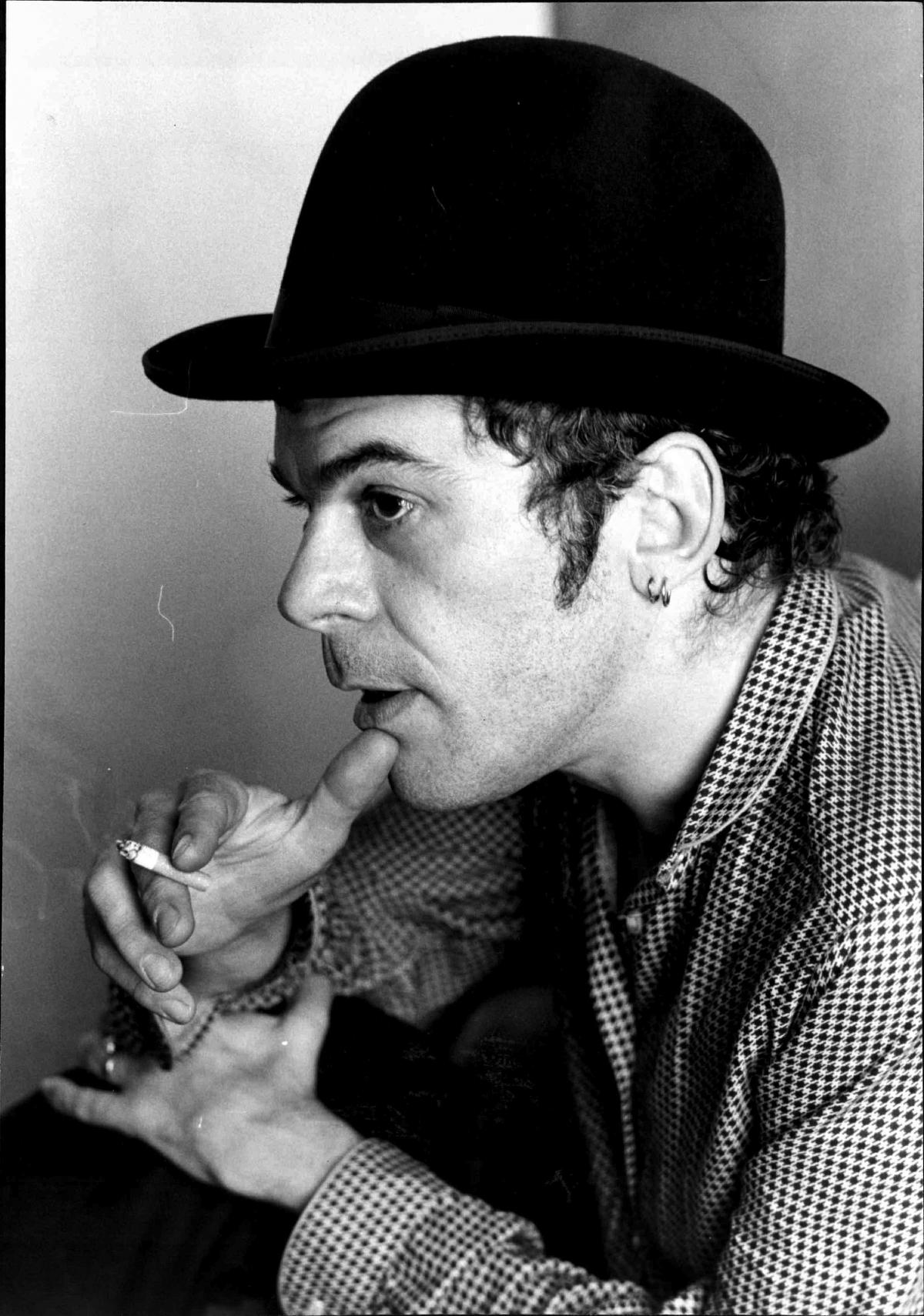

TALK of Baxter Dury’s recent album has usually focused around it being a break-up record, comparisons to his late father Ian or the vivid, often filthy character vignettes that it paints. The man himself has a more straightforward viewpoint on what kick-started Prince of Tears, his fifth album and a record that he will bring to Scotland later this month.

“It’s always the rent that makes you work,” he says with a chuckle.

“You’ve dug a hole in this position, and then you go, ‘wow, I can’t go back because I can’t see where the land is, so I’m not going to go and train as an optician now,’ and making music is what I have to do. Apart from all the heartbreak and the creative side, it’s just about working.”

Dury has sandwiched this interview in between a couple of domestic tasks, namely trying to find a plumber to fix a problem in his flat, and then picking up his teenage son from school. Yet later this year he’ll be performing in arenas, thanks to a support slot with Noel Gallagher, while material from this record has found a fair amount of radio airplay (albeit in a censored form).

If the idea of Dury as a pop star seems ridiculous, then there should be no doubt that Prince of Tears is his most accomplished work yet, possessing swagger, confidence and a cutting, comedic tone, along with some string arrangements and a musical palette ranging from bass-driven funk to punky brevity.

It’s a much different beast to the folk-flavoured style of his 2002 debut, Len Parrott’s Memorial Lift, and the inevitable comparisons to his father have flooded in, based on both the darker, foul-mouthed lyrical bent and the skilful character creations running through it, from the on-the-rebound protagonist of Miami to the nostalgic memories of a violent old friend on Oi.

For Dury himself the album owed much more to his then state of mind, which had just seen the end of a long-term relationship and his girlfriend moving back to France. Dury himself then headed back to London from a village near Hertfordshire early on during the writing process.

“I was just naturally informed by my state of mind, which is quite good because it means you have a starting position,” he explains.

“If you’re neutral and start writing songs, and you’re talking about, I dunno, dolphins or some other miscellaneous subject, then you end up making an album about nothing. This time I was a bit miserable, and I don’t have a sentimental bone in my body, so this was never going to be an album claimed by cheesiness. It was my version of my emotions and I don’t think I can be cheesy about things like that.”

Dury’s first taste of music fame came as a child, when he was pictured for his father Ian’s classic New Boots and Panties album, released in 1977. He had an upbringing usually described as bohemian, and only started to release music after his father had passed away from cancer in 2000, with the younger Dury singing at his father’s wake.

However this is not a chat to reflect on his family ties yet again. There was always a love of music there, and it was always a passion for him.

“I always liked music, it wasn’t like I had an epiphany in 2000 or 2001 saying that I needed to make music. I had run out of other choices, really because I’d been going round in semicircles. I made the choice that I would rather be defined by something, rather than nothing, and I thought this is the closest thing I have got to having a skill.

“It then took a long time to get to the point I wanted to get. The music I make is quite complex in how you build it up, and it takes time to get good at that. It’s about selling the unobvious while making it accessible, and that’s quite difficult. I’ve just got better at it over the years. I’ve always done it really, with everything, it just took me a long time to get here.”

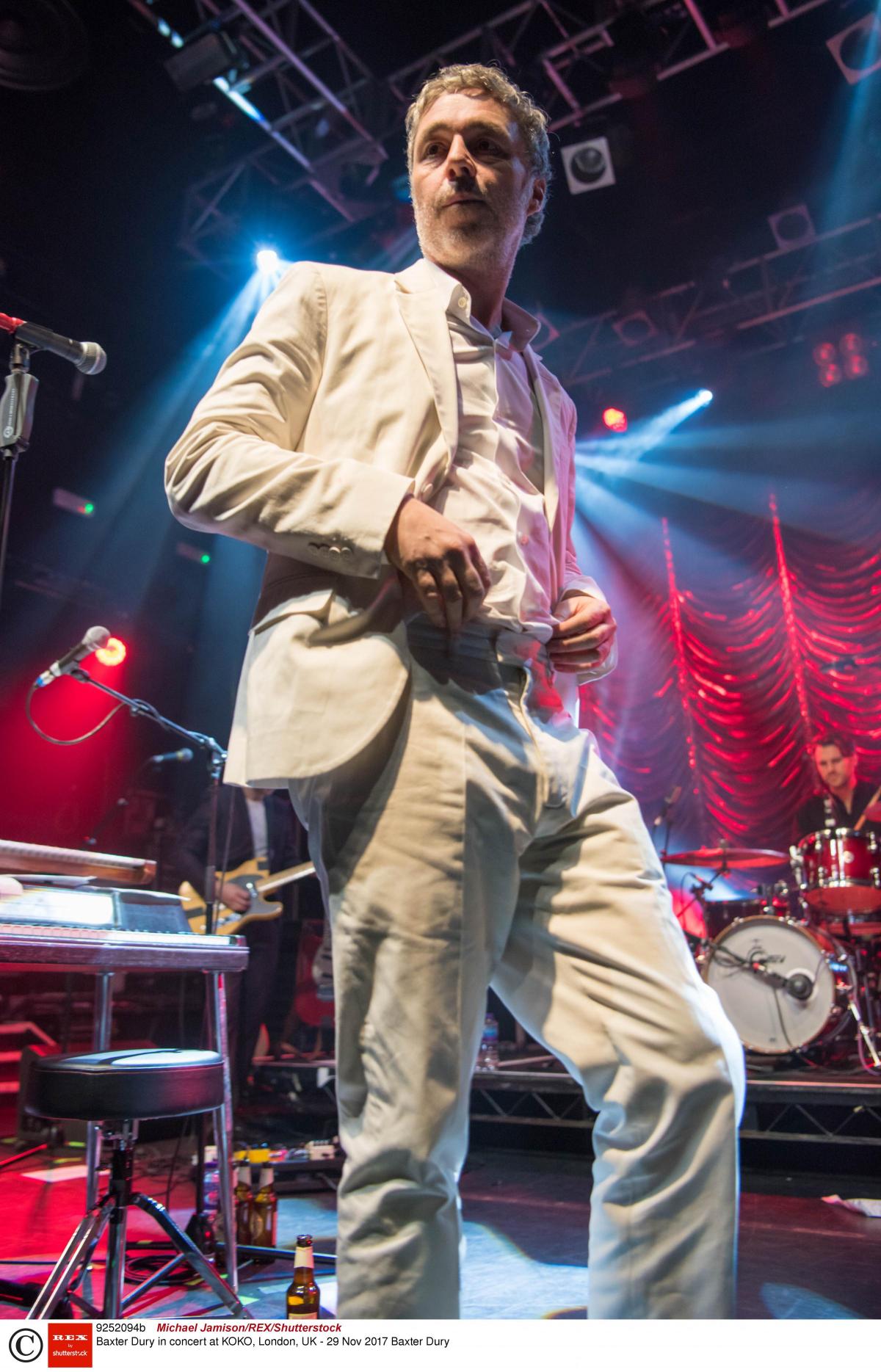

Now in his 40s, Dury says the next aim is to get better as a live performer. He will have that chance on February 20, when he plays Stereo in Glasgow as part of a UK tour.

“I love it in Glasgow. It’s always a bit of a carve-up there, where something happens or someone turns up. I always feel like I meet a gangster or something when I’m there but I like it a lot. I feel I can relate to it as a city, because there’s a romantic bleakness there that I like.

“I can’t explain it really, there’s a bit of that in me too, and there’s still a toughness there, at the core of it. It’s not about how many coffee shops you build there, it’s about something else and I feel Glasgow always has that when I’m there.”

Stereo has already sold out, and he’ll be back at a slightly larger venue in April, when he supports Noel Gallagher and his High Flying Birds on the former Oasis man’s lengthy arena jaunt, which includes an SSE Hydro stop.

Dury has played some big gigs before, particularly in France, where he is much more popular than in the UK. Still, arenas on a nightly basis figure to be a new experience for him.

“I think he [Noel Gallagher] must have heard one of the songs we did, and I thought it’d be a nice tour to do. I’ve played a few big gigs here and there but never anything like an arena tour, so it’ll be an interesting one.”

Dury’s own songs tend to be interesting, too. Prince of Tears might have taken primary inspiration from piecing things back together after a break-up, but it is hardly an album of singer-songwriter bleating. Dury’s style owes much more to creating characters, and there’s a cinematic inspiration bubbling away throughout.

“I always see a song as like a dream sequence in a film, like an episode of the Sopranos or a Coen brothers film,” he adds.

“It should be like one of those slightly hallucinogenic dreams, tied together around a loose, spasmodic narrative, and they do so well at them. There’s a Sopranos dream sequence where a fish starts talking [in the Season 2 episode Funhouse], or the bowling bit in the Big Lebowski – those are totally what I’d like to do with the songs.”

Prince of Tears came quickly to Dury, and at one stage he mentions the finished album not being too different from the initial demos he assembled. Guests such as Jason Williamson of Sleaford Mods and songstress Rose Elinor McDougall dropped by, with Metronomy collaborator Ash Workman co-producing.

The core, however, were the early songs that Dury penned. A swift writer, he admits that the initial ideas arrive quickly, then take time to fully develop.

“I always write the lyrics quickly, then really slowly dissect it. So I like them really quickly, hate bits of them slowly, and then like it again. It all builds it up – sometimes I write the lyrics so quickly that I don’t think they can be valid. Then later on I’m like, ‘actually, that’s really good’.

Prince of Tears has been greeted with fine reviews and many selections in best of 2017 lists, and Dury himself has struck a confident tone when discussing it. That hasn’t always been the case with his past releases, and he admits that he had a good feeling about the quality of this release from an early stage.

“You suspect something is quite good, but you’re never totally sure that your suspicion is right, so it’s been a nice process the past few months,” he says.

“I don’t think I’m too self-critical, but there were reasons to be let down in the past, and you should only be confident when it’s good. There’s an effort, and you learn a bit more about packaging your message better, which I think I did this time.

“I don’t think about it too much after we’re done, I just want to get on with it. Personally, I’m happy with what I’ve done, so that personal battle is won – now it’s about everyone else, but I’m happy.”

And now he can sit back and watch the money come rolling in. Except, of course, that’s no longer an option in the music business these days, unless you’re an Adele or Beyonce level of mega star. Dury is unfussed though, by the money that he could have earned at other points in pop history, or how the business has changed so dramatically since the days of his father.

“It’s all relative, because you get less but you learn to appreciate it more,” he says.

“You would have two million quid in the 80s, but you wouldn’t even have known you had it, other than buying an ice sculpture for your house or something. Every single one of those bands didn’t know that they had those amounts of money going around.

“A lot of them were still miserable – you have to quantify what you’re getting through work, which is a weird trick. You can have children of folk with fortunes that are miserable, because a world without boundaries doesn’t work.”

Speaking of children, Dury draws our conversation to a close as he heads off to pick up his son Kosmo up from school. Already it seems possible that there could be another generation of the Dury family with musical talent in their bones, although the singer admits that his son won’t be taking much inspiration from his father’s musical stylings.

“He won’t take any of my advice,” Dury concludes. “He’s a very good musician but he’ll never listen to me. Which I guess is the right idea – the last thing you want is for you son to think you’re great, because you’ve failed as a parent if your kid thinks you’re cool. It should be in your contract as a parent that you mustn’t ever be iconic or anything like that to your kids.”

Baxter Dury plays Stereo on Tuesday February 20. Prince of Tears is out now.

FIVE SONGS THAT INFLUENCED BAXTER DURY

Plaistow Patricia, by my father

This captured my imagination and sense of adventure before I understood anything about music. I knew it was gritty and unforgiving and that's all I needed. My neighbours at the time were a strict Pakistani family and the two kids Amjul and Amjid were my best mates. We would listen to the opening sentence so loudly and they would inevitably get slippered by their dad.

Sweet Nothing by the Velvet Underground

Opened up the pale roots of indie music to me. It's a sacrilegious song amongst devotees as Lou's not singing but Doug Yule does his best. It's slow and repetitive and naively soulful because of Moe Tucker’s drumming.

Planet Rock by Africa Bambatta

This was a key song in becoming an individual. Only Tim Westwood would play this type of music in the early 80s on radio. It defined change in the music world at that stage as it was pretty low fi and underfunded music coming out of poor black America. Now it's has a welcome innocence to it compared to some of the modern chrome plated s*** cooked up in a cynical hit lab.

How To Mend A Broken Heart as sung by Al Green

Written by some goofy Australians and sang by a preacher it conspires to be an almost perfect moment in what is great about something so sad.

Love Will Tear Us Apart by Joy Division

A statement and a melody hanging of some poorly executed but well thought about music. It's so fragile in every way but all of it so strong.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel