THE thing about Lincolnshire, Jim Broadbent tells me, is it’s all on the horizontal. “Not one cliff. Some dunes, but not magnificent dunes. It’s very flat, very marshy, very sandy. I love all that. It’s always empty, if not bleak.”

This does not appear to be a drawback for him. Do you like the bleakness, Jim? “Yes, I like it. You’re on your own. It’s utter space. It’s wonderful.”

He smiles, and I begin to think that right now it’s possible that on the whole Jim Broadbent would rather be in Lincolnshire.

Instead, he is in an office in the centre of London talking to me about his new book, his glittering theatrical and cinematic career and life growing up as the son of wartime conscientious objectors in, yes, Lincolnshire. He has left his wife Anastasia Lewis at home suffering from shingles. She chased him out of the house, he says.

He is not, I think it’s fair to say, naturally exuberant. When it comes to Broadbent there’s a party line amongst journalists. Great actor, terrible interviewee. Time and again, his interviewers have come away fretting over his general diffidence, the way he swallows his own sentences. The lack of great anecdotes. In the past Broadbent has said that even he thinks he’s boring.

And I’m here to tell you that … well, yes, most of that is true. He is not boring, no. But he is certainly not a natural raconteur. As he talks, or often doesn’t, his eyes slip away to the side of my head. There are long pauses between his words. He will start to essay an answer and then pulls it back before it really starts to breathe. Sometimes you can hear the ghost of a stutter.

So often on screen – think of his role as Harold Zidler belting out Madonna tunes in Moulin Rouge! or toting guns in Edgar Wright’s comedy Hot Fuzz – he’s a widescreen presence, eyes wide, head gleaming, tufts of hair as electrified as the rest of him.

In person, however, he retreats into himself. He’s more 20-watt bulb than full-on fireworks. More Mr Gruber in the Paddington films than Zidler.

And yet, there’s a droll humour to him, and now and then he offers you a quick glimpse of the man behind the mask that makes you wish he would give you more.

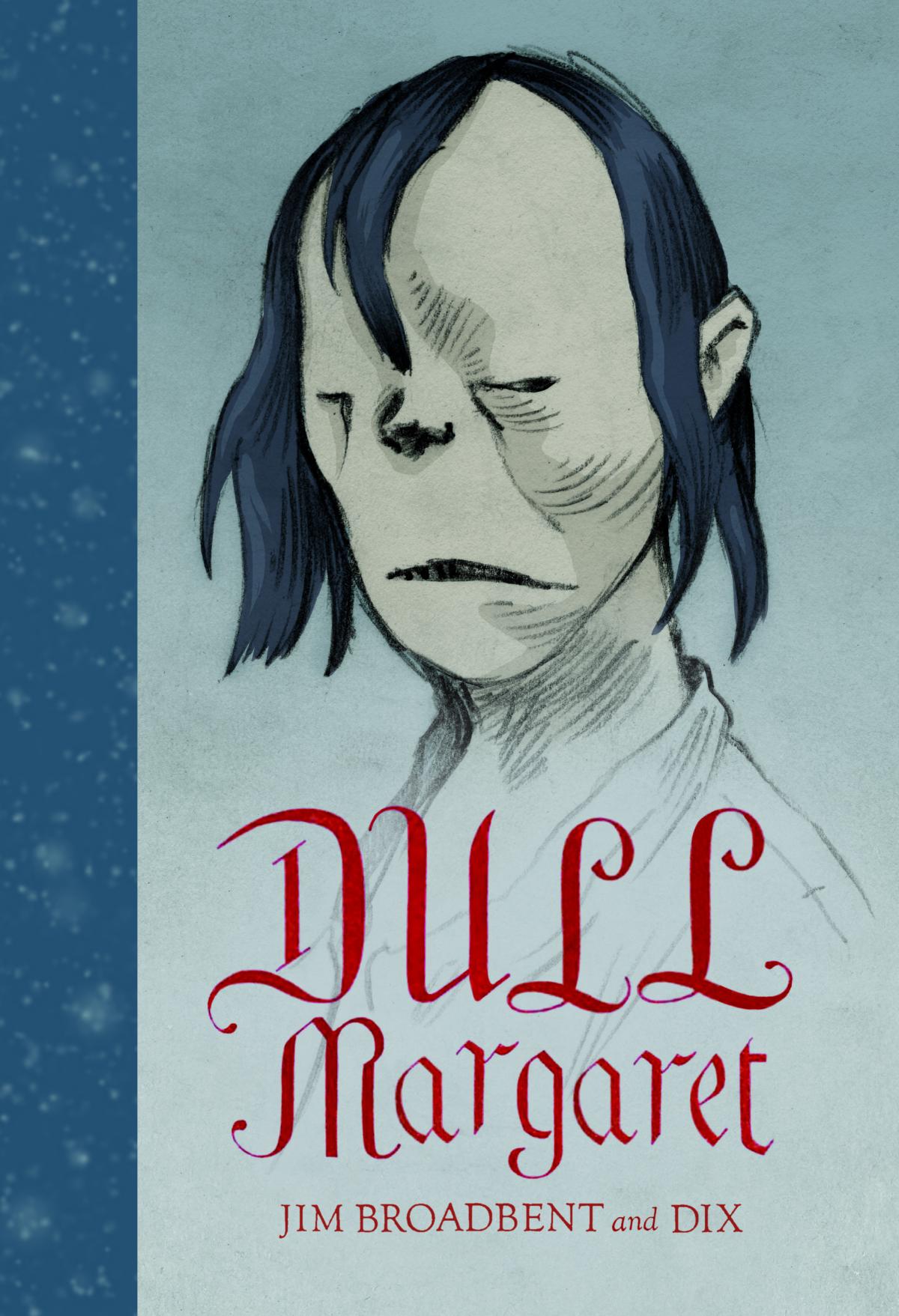

The reason we’re here is his latest work. Not a film or a play this time, but a graphic novel. Dull Margaret is a strange, wild, possibly medieval, possibly futuristic story (“It’s timeless, really,” Broadbent says), set in a marshy landscape (not unlike Lincolnshire, it might be noted) about a woman who lives off whatever passes by her hovel and who cuts off the hand of a hanged man to use in a spell she’s casting. If she’s not a witch, she’s certainly witchy. She even jumps on a broomstick at one point. But she’s also clearly an outcast, a powerless marginal figure who at one point finds herself in charge of an old man who she ends up both torturing and loving.

“I think it’s that sort of childish instinct that I quite like in her,” Broadbent says. “She’s horrible to the old man in the way a child is horrible to a puppy. She’s horrid but she’s vulnerable and loveable.”

Drawn by the cartoonist Dix, it’s a grotesque, compelling narrative full of violence and avarice and dark humour. It very much reflects Broadbent’s own tastes, he suggests.

If it was a film you could imagine it as some mad Ken Russell romp full of nudity and horror and wriggling eels (“Eels have fascinated me for a long time,” Broadbent says). In fact, he originally wrote it as a film script, but he couldn’t get anyone who would put the money up. “It didn’t fit any known genre,” he admits.

“It occurred to me early on that it could be a graphic novel. It’s a series of images. It’s not a dialogue-heavy piece by any means.”

When it was clear he wasn’t going to get it made he got in touch with Dix and the graphic novel was born.

He started writing the script some time ago, he says, at a time when acting wasn’t the main thing on his mind. His mum had Alzheimer’s and he was nursing her.

“I think my mother was dying at that time over quite a period of time, so I didn’t want to get heavily involved in anything.

“When I’m not acting I want to do something creative.”

Sometimes that means carving human figures out of wood, one of his regular hobbies, and sometimes that means writing a piece that could become something or someone he could play himself.

For a while he thought if Dull Margaret did get made into a film he could play Margaret himself. And he’s played women before, he points out. Back in the 1980s when he was working with Patrick Barlow in the National Theatre of Brent (the comic bathos of that title tells you all you need to know if you never saw them) he points out he played Marie Antoinette and the Virgin Mary. And in 1977 he remembers playing some “seedy waitress” in a Fringe revue. “I really enjoyed it. There’s a lot of fun to be had.”

Hmm, what’s your most feminine attribute Jim. “I don’t know.” He starts laughing. “It comes out as a sort of vanity, I think. I wouldn’t know really.”

Later he will circle back to this when he tells me the one thing you must let go of to be a good actor is vanity. Was that difficult, I ask?

“Not for me. You have an ego, but you don’t want to be vain. Vain is the killer, really. You see someone who is more interested in putting themselves across than finding the character … I can spot it a mile off.”

Broadbent is such a familiar face now. According to Imdb he has 157 acting credits to his name. He has turned up in everything from Game of Thrones to The Iron Lady (he played Denis Thatcher). You might remember him as a Spanish translator in Black Adder or playing the title role of Lord Longford in the TV drama based on the life of the British politician and social reformer who famously campaigned to get parole for Moors Murderer Myra Hindley.

That said, when he’s recognised in the street, the two roles people always mention are Professor Horace Slughorn in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince and the corrupt copper Slater in the BBC sitcom Only Fools and Horses, which was 30 years ago.

Which reminds me, I say. Was it true that he was up for the part of Del Boy at one point?

“I wasn’t available. I would have gone for that if I hadn’t been doing a play. I wouldn’t have stuck it through two or three decades. So, you would probably never have heard of it.”

He has a raft of awards to his name. Baftas and Golden Globes and the like. In 2002 he won a Bafta for Moulin Rouge! And in the same year an Oscar for Iris, in which he played Iris Murdoch’s husband John Bayley opposite Judi Dench in a story that charted the author’s battle with Alzheimer’s. Broadbent drew on his own experience with his mother.

He doesn’t brush the awards off. “It’s great. It’s very confidence-building and very useful. People like to get ‘Academy Award winner.’

He says the last three words in the voice of a film trailer voiceover.

“But then it entirely stops you being competitive in the same way. You don’t resent other people. ‘Why have they …? That should be me.’”

That’s how you thought then? “Yes, in some way.” Really? “In your own way you think: ‘Shit, what’s he doing there? But not so much, because I was having great choices and options to work with great people anyway.”

What he looks for in a role in something new, something risky. That doesn’t scare him? “No, I always want to take a bit of a risk somewhere. That’s not scary. Scary is not knowing your lines and making a complete fool of yourself.”

When was the last time you corpsed? “Corpsed?” No, I say, I mean “dried,” don’t I? “Corpse all over the place. Dried? I think it might have been on the first preview of the last play I did. Corpsing’s fun. Drying is agony. Corpsing is delicious. It’s a sort of wicked joke beyond all others.”

Jim Broadbent’s parents Roy and Doreen were themselves amateur actors as well as being artists. During the Second World War they decamped to Lincolnshire to work the land. They were conscientious objectors, part of a “pacifist community” who refused to participate in the war.

“They were all of conscription age,” he says of his parents and their friends. “I think there is only one parent from that generation left. He’s got his 99th birthday at the weekend.

“None of us second generation have died yet. We’re going to start popping off soon,” he says and then laughs.

Broadbent was born in 1949. A second son. His twin sister died at birth. It was a rural childhood. “Nearly all my friends at that time were farmers’ children.” He spent his teens bailing and stacking for pocket money.

“There was never any antagonism or bullying. Nothing like that. My friend had riding lessons with a major who had a riding school. He loved the idea of getting me and Chris to go hunting. He’d love to have got a couple of conchies at the hunt.”

Lincolnshire people, he says, are “very accepting.”

Had that been the case for his parents during the war? “There was no feeling of paranoia. I think they started businesses, had farms and employed people. They weren’t isolationist in any way. It wasn’t a commune. It was a community that quickly dispersed in the area and everyone became part of the community.”

Broadbent himself went to a Quaker school and ended up being expelled. “I had to leave immediately after my A levels. I said: ‘Does this amount to expulsion, sir?’ ‘Yes, I’m afraid it does.’

“It was disappointing not to do the leaver’s play. We were going to do The Long and the Short and the Tall. I was going to play the Geordie. We were mercifully spared my Geordie accent.

“I wouldn’t have had a clue then what it was. Regional accents in the late sixties weren’t on the telly all the time. Certainly not strong ones.”

Why was he expelled? “Just drinking. Caught in the pub, four of us. We were 18.”

You were expelled for one incident? “No, I’d like several other cases to be taken into consideration.”

After getting chucked out of school he worked for six months in a theatre in Liverpool then went hitching around Europe before going to art school to do a foundation course for a year. “I was thinking about stage design and then realised I wanted to do acting.”

We’re talking about the end of the 1960s by this point. How much did that decade impact on him? “I wasn’t an out and out hippy. But, yes …”

When his brother’s sixth-form class had their school photos taken “they all looked like their fathers,” Broadbent suggests. “Men with sports jackets trying to look like they’re 40. My school photo six years later, we were all hairy and trying to look as unlike as our parents as possible.”

The problem was, he says, is that his hair “didn’t get long in a cool way.” Plus, he says, he was too focused during the 1970s to fully embrace the counterculture. “I was too excited by the acting and the fun to be had there. So, I didn’t get completely distracted by … drugs.”

When he left drama school he gave himself 10 years – or maybe it was until he was 30, Broadbent can’t remember now – to make it. “‘If I’m not working after 10 years I’ll do something else.’ But it was all right by then.”

By the mid-seventies he began to be a regular at the Fringe. He got in touch with the English writer-actor-director Ken Campbell (“totally anarchic and brilliant”) a call. Campbell gave him a part in his science fiction epic play Illuminatus! It was eight hours long. Which was nothing. Campbell then staged The Warp which lasted the best part of a day (22 hours in fact). Broadbent was part of that too.

“Then I got an agent and I became entirely usable. I did a lot of fringe theatre and at that time there was a big crossover between directors working in fringe theatre and [the BBC drama strand] Play for Today. So, you get into TV and film.”

What would he miss if he couldn’t act anymore? “The sociability of it all. The various companies and the laughs that come with that. I’d miss that.

What wouldn’t you miss? “I’m about to do theatre at the end of the year. It’s going to be a 14-week run. I won’t miss that after 14 weeks, six nights a week. As you get older that becomes harder to do, particularly domestically. It’s not fun for my wife.

“But I am quite picky about what I do and generally the jobs I do I really enjoy.”

The thing about love, Jim Broadbent tells me, is “you don’t have to analyse it. It’s there.” The thing about death? “It doesn’t bother me, death. Not so much as incapacity of any sort and, as a couple, the fact that one of us is going to be alone.”

Is age just a number? “Yeah in a way, but I’m in the higher numbers.”

Of all the roles he’s played, I ask him finally, which one is closest to himself? “Don’t know. There are some I haven’t had to physically change a great deal for. I haven’t had to make a conscious leap away from me.

“But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s closer to me and my life.” He mentions the recent film The Sense of an Ending, based on the Julian Barnes novel, in which he plays a man of similar age and class to himself.” But, actually, I wouldn’t have behaved in that way at all. That’s perhaps no nearer to me than Zidler in Moulin Rouge.”

Hah, I say, that’s the secret isn’t it? You spend your days wandering around the house singing Madonna songs all day. “Yeah, it happens,” he says. He waits a beat and then adds: “I think of them as my songs.”

Give him time and Jim Broadbent knows how to hit the high notes. Unlike Lincolnshire, obviously.

Dull Margaret is published by Fantagraphics Books, priced £25.99. Jim Broadbent and Dix will be appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on Thursday at 3.15pm.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here