For the Glory: The Life of Eric Liddell from Olympic Champion to Modern Martyr

Duncan Hamilton

Doubleday, £20

Reviewed by Hugh MacDonald

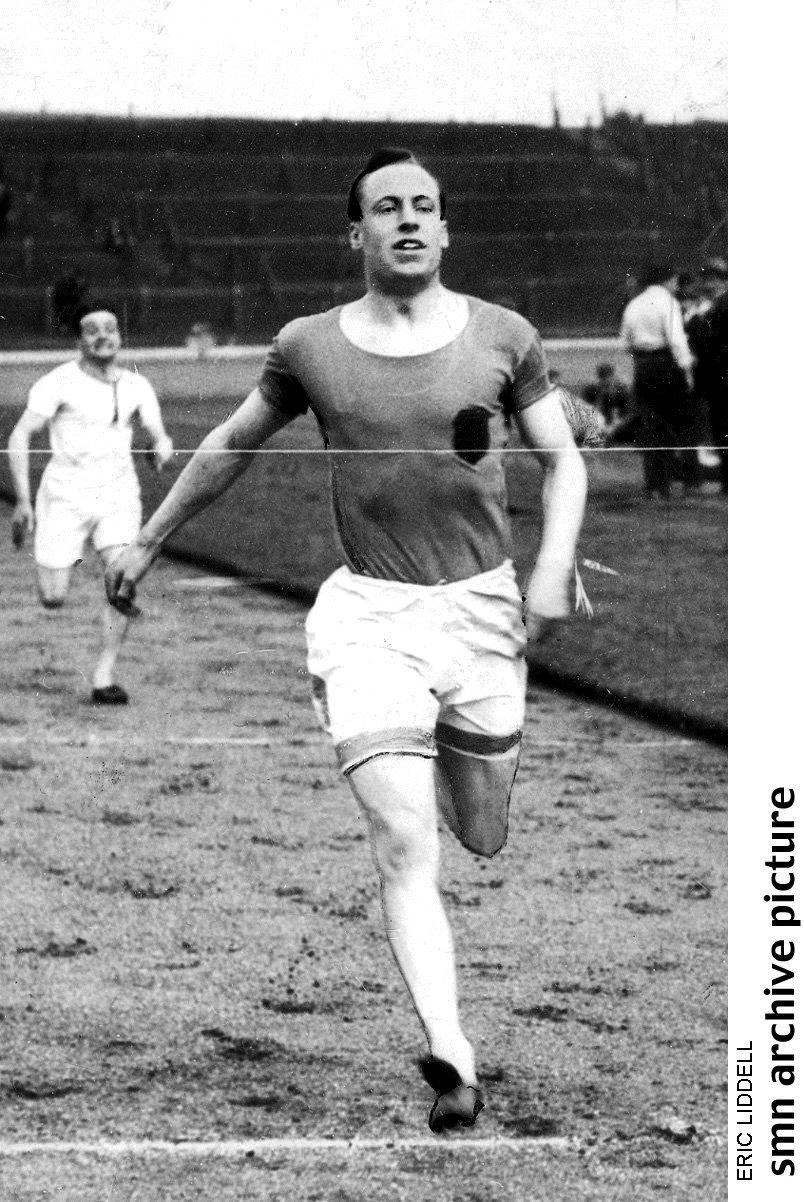

THERE is a paradox at the heart, and certainly the soul, of Eric Liddell. A majestic, dynamic irresistible sprinter, a redoubtable man of action, he is remembered for what he did not do. It is a strange fate for a consummate winner but Liddell’s defining moment was his refusal to run on a Sunday, thus sacrificing an excellent chance of a gold medal in the 100 metres at the Paris Olympics in 1924.

Viewers of Chariots of Fire may recall that the Scot did, however, compete in a Sunday-free 400 yards and win it sensationally. This extraordinary run in his least favoured event remains neglected as generations remember his obstinate, courageous and principled stand on keeping the Sabbath holy.

The paradox to Liddell, one that stretches into the depths of his being, is best captured by the realisation that his favourite scripture was the Sermon on The Mount. Filled with seeming contradictions, unlikely truths and challenges to accepted human behaviour, it became Liddell’s template for life. He studied it almost daily. More relevantly, he sought to live it.

The triumph of Duncan Hamilton’s moving, inspiring book is not that it covers brilliantly an exhilarating, unlikely sporting career. It does all of this, of course, as Hamilton has fine form, being a double winner of the William Hill Sports Book of the Year. His finer achievement, though, is to give a sense of a good man. There are moments when Hamilton seems to protest gently that he struggles to find anything truly scabrous to say about Liddell. The best of biographies normally need this grit to produce the perfect oyster. Hamilton is left with a subject who is universally praised as an athlete, lauded as a preacher and revered as an inmate in a Chinese camp under Japanese control in the Second World War.

Hamilton thus comes close to hagiography, at least in its literal terms. There is much of the saint in Liddell and it seems perverse for even the most cynical to deny it. This is a man who led friends, trainers and fellow prison inmates to name their sons after him. It is the most sincere of tributes.

Liddell, too, suffered the martyr’s fate of an early death. He was 43 years and 37 days old when he succumbed in 1945 to an undiagnosed brain tumour in Weihsien camp. He had been suffering from awful headaches, dizziness and fatigue but doctors put this down to a “nervous breakdown” caused by overwork in the service of others. Typically, Liddell was bruised by this diagnosis. His way of living was to surrender everything to the will of God. Had he not been entirely faithful in this? How could he be tired doing the work of God? Had he been living a lie? The answer from the witnesses in the camp is overwhelming. Liddell was not only industrious, but caring and compassionate. He lived what he preached.

He was also far from rigid in his thinking. He collaborated with black market operations – sniffed at by many moral guardians – because he believed they sustained the most weak in the camp. Tellingly, he agreed to referee Sunday sports, breaking a stance which cost him a gold medal. He acceded to Sabbath sport in the camp simply because it would help inmates, physically and psychologically.

The road to the camp and to death was sprinkled by moments of mundane glory. Born in China to a missionary father, Liddell found he was an exceptional athlete under the ministrations of a faithful trainer, Tom McKerchar. Liddell won 200 medals in his brief athletic career but he could have won a hatful of Olympic golds. He was superb at 100, 200 and 400 metres and could have competed in three Olympics instead of just the one.

He was adamant that giving his life over to God meant just that: immediately after the Paris Olympics he took up a missionary post in China. This was to be his life’s work. His conversion to a fully religious life was made on the road to Armadale. He preached there, somewhat diffidently, as a student at Edinburgh University but was a major attraction because of his sporting fame. His congregations subsequently grew and grew and so did his confidence in addressing them.

The journey to China was almost inevitable with Liddell becoming a disciple of a missionary father he revered. It was to be a crucible that threatened and then took his life. It was a merciless forge that tested and then strengthened his faith. The China of the 1930s and the 1940s was a brutal landscape, plagued by bandits, scourged by civil war and then invaded by a Japanese army that was ruthless and more than occasionally murderous. Liddell met all of this with a bravery that owed nothing to cheap bravado but everything to his belief that he must act out of principles and these could be divined by consulting the Bible, particularly the New Testament.

This was a simple approach but, of course, it was not easy. The sacrifice for Liddell was a family one. He sent his wife and children to safety while remaining in China to accept, ultimately, death. His marriage seems uncommonly happy. Liddell was entranced by a younger woman. It is no surprise to learn that the first time he kissed her was when she agreed to marry him. They had three children, one of whom Liddell never saw.

This enforced separation, of course, caused strains. It was difficult for the children to accept their father’s premature death, more distressing to consider that he had chosen the danger of continuing missionary work over the chance of safety in Canada with a loving family. It took at least one of the daughters some time to reconcile herself to this reality.

The truth, of course, is that Liddell could do no other. He was welded to his faith. He was always prepared to make accommodations for others. He was no brow-beating preacher. His maxim was to live and let live but he knew how he had to serve his beliefs totally. This made him a hero of the camps. He managed to run a race to boost morale while in the final stages of that fatal brain tumour. He finished second and congratulated the winner before staggering off in exhaustion.

It was this moment that reveals more of the man than any Olympic bauble. “He was pure gold” said one intimate. He was beset by trial and his faith was tested as he struggled to maintain his spirits, almost certainly diminished because of his illness. He was disconsolate at this development but he worked through it, he prayed though it.

Hamilton has thus constructed much more than a life of a sporting hero. Liddell died almost abruptly on a bed far from his family. His last words were recorded by a friend at bedside. “All is well,” he said. He had run his race. He may be remembered for that sprint not undertaken on a Sunday long ago. However, Hamilton’s tribute makes Liddell unforgettable for what he did, how he lived and how he loved.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel