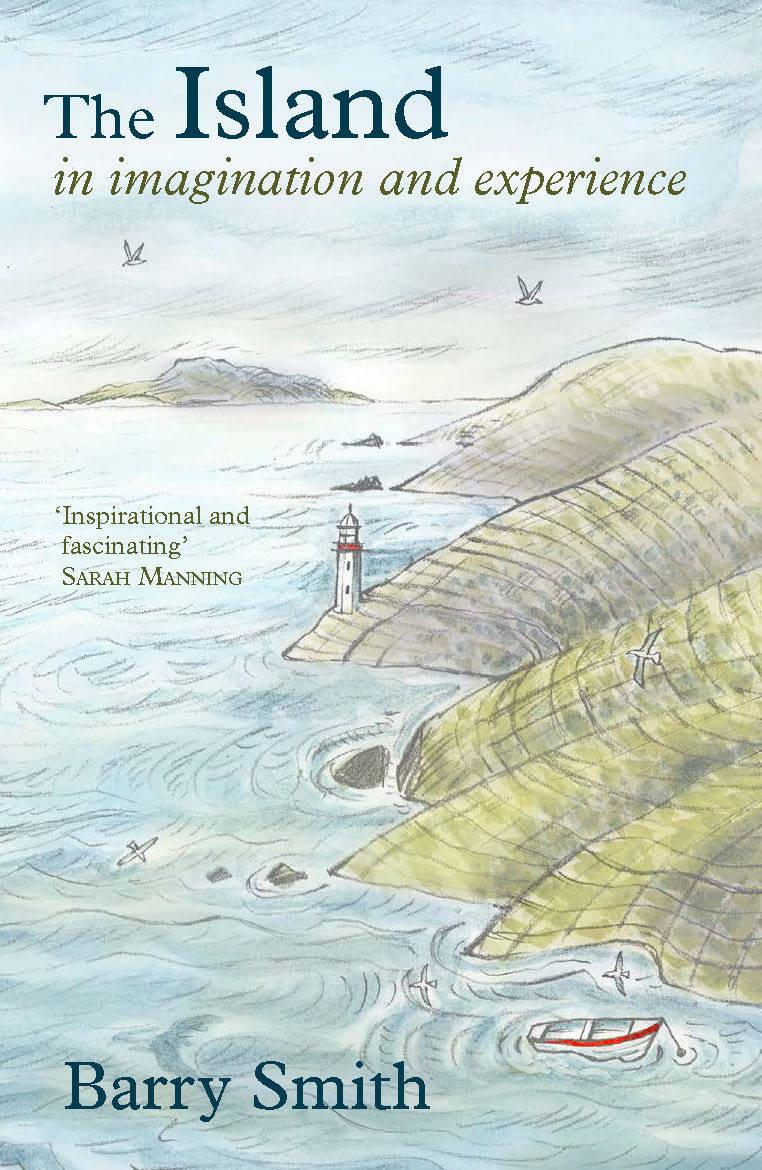

The Island In Imagination and Experience

Barry Smith

Saraband, £12.95

Reviewed by Alan Taylor

THE life of an islander is rarely as rosy as it is often portrayed by copywriters. Islands, especially small ones, are claustrophobic spaces where every move you make is monitored.

I have often thought that the security forces could learn a lot from surveillance techniques of islanders. On one Scottish spit where I spent a couple of days the barmaid in the local hotel was as indiscreet as she was malicious.

No one, not even her husband, was spared her bile as she poured a pint. Yet an hour or so later she was bonhomie personified as she welcomed regulars whose names she had blithely blackened earlier. Whenever I need to define hypocrite I think of her.

On another occasion, thanks to the weather I came as close as I probably ever will to being marooned. The island was Ailsa Craig. Just landing on it proved too much for several of my fellow passengers who, as our uncovered boat was buffeted by the swell, brought up their lunches even faster than they had bolted them. Once upon a time the island had been home for several months of the year to men who quarried its granite, which was used to make curling stones. A more recent resident, I learned, was a young researcher who was studying the island’s bird life for a PhD. His stay, however, was involuntarily extended because of atrocious weather and by the time of his rescue the poor fellow was down to his last few tins of baked beans.

I doubt he shares Barry Smith’s love of islands. Like Lawrence Durrell, lyrical memoirist of Rhodes, Cyprus and Sicily, Smith suffers from islomania, “a rare but by no means unknown affliction of the spirit” which grips those “who find islands somehow irresistible”. In The Island In Imagination and Experience, he traces our fascination with them from ancient times to the present day, through the Greek myths and the travels of intrepid explorers and adventurers to the era of reality television programmes in which attention-seeking narcissists eagerly sign up to “make a new society on an island”. It does not take long, however, for the image of a tropical idyll to fade and the reality of diarrhoea, dehydration and the difficulty of living with people whom you can’t abide begins to surface.

Smith’s first experience of islands were those near his childhood home in Essex, such as the Isle of Dogs and Canvey Island, neither of which could fairly be described as paradisal. The one that fired his young imagination was that which, as a schoolboy, he thought of as belonging to him and his brother. It lay in the middle of a lake that always froze in winter. Once, however, it didn’t freeze hard enough and the siblings nearly met their demise. Unsurprisingly, Smith remembers it still. As he grew older he collected islands as others do stamps or Munros. His is an indiscriminate obsession; he likes islands whether they’re in Alaska or Anglesey. He reckons he has “claimed” 153, by which he means “staying overnight on, moored to, or at the very least anchored off the piece of land”. Being a kayaker doubtless helps his quest. Now in his sixties, he hankers for “the days when a pair of boots, a rucksack and a map...were de rigeur [sic] for geographers to pursue their trade”. He himself has completed a doctoral dissertation about islands.

Thankfully, his book is not blighted by academic jargon. On the contrary, it explores islands through the stories of people who have written about them – Daniel Defoe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Herman Melville, Patrick White, William Golding – or have lived on them, either by choice or circumstance or through the imagination. Islands are places of escape and renewal, of an opportunity to test theories or distance oneself from other people. In that regard, they are like laboratories. But they are not, as Smith amply records, places amenable to the mentally unstable and physically disabled. Their isolation means that the inhabitants must rely on their own resourcefulness to get themselves out of a jam. Do your back in on an island and it could be the end of you.

This will never, of course, deter people from dreaming of living on one. The tale of Tom Neale is instructive. His 1966 book, An Island to Oneself, like Robinson Crusoe long before it, enchanted many and encouraged them, if not to replicate Neale’s adventure, then to visit Suvarov Atoll in the South Pacific, of which on and off from 1952 to 1977 he was the sole resident. The island was tiny – a mere three hundred yards at its widest point – but it did have fresh water and an abundance of wild produce and fish that appeared eager to be caught. But it was no earthly paradise, as Smith underlines. It was prone to hurricanes and its occupier to depression. At one point, Neale even thought he could no longer eat fish. Why he chose to go on living there is unclear. He was married and had a daughter. Was he a recluse? Smith argues not: “He was a man of his time rather than an unconscionable hermit.”

What marks many islanders is a desire for a simpler, more elemental life. This, though, is rarely achievable. For the fact is that human beings are innately complicated and aspirational. We are insatiable improvers; it’s what distinguishes us from other animals. It’s not in our nature to leave things as they are. Nothing Barry Smith says makes me want to live on islands but if you want to read about them, he’s your man.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here