The Golden House

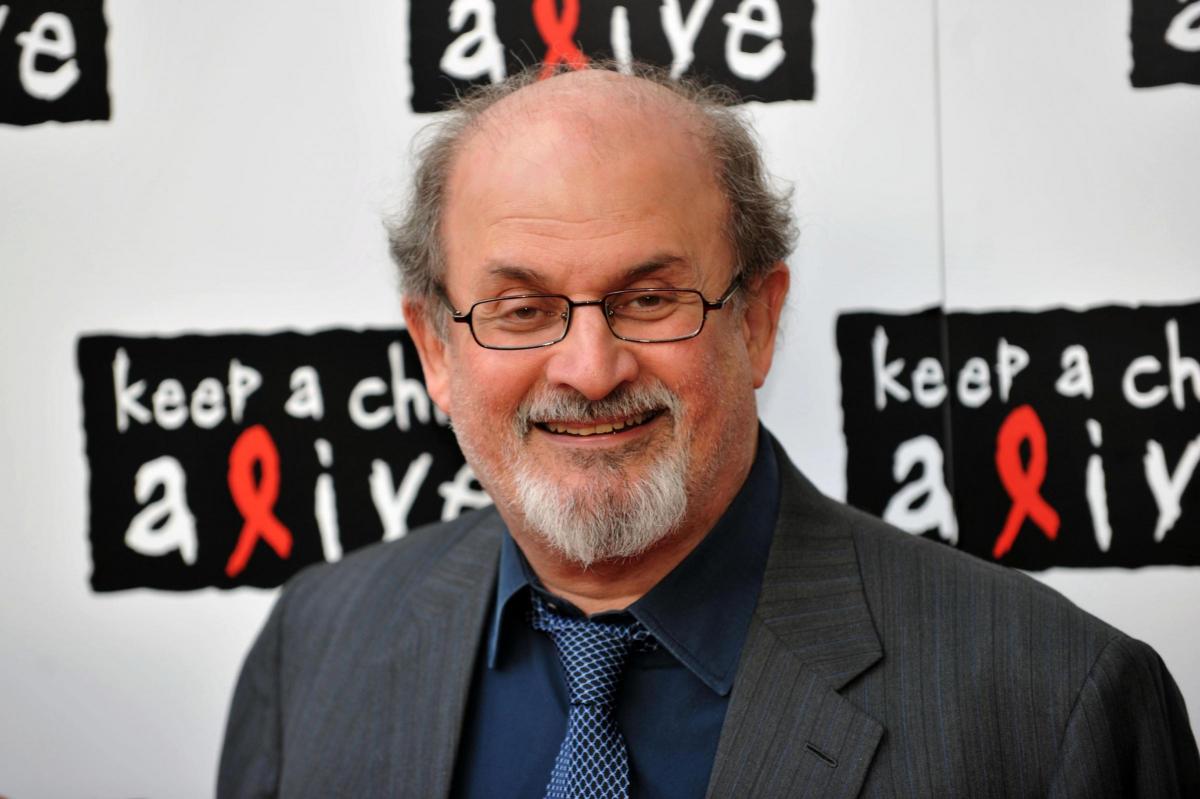

Salman Rushdie

Jonathan Cape £18.99

Reviewed by Stephen Phelan

FOR 20 years or so, even those who did not read Salman Rushdie's books were following his story – from that emphatic Booker-winning Midnight’s Children, to the holy war declared against him for The Satanic Verses, to his last real blockbuster, The Ground Beneath Her Feet, at the turn of the millennium, which came with its own (woeful) theme song by his pals U2.

Rushdie moved to New York around then, which seemed to mark the start of a decline. His 2001 novel Fury, published barely a fortnight before 9/11, took that city as its subject, and was generally agreed to be the worst thing he’d ever written – stale, priapic, floundering, irrelevant. Now he’s got another New York novel, which sees the 70-year-old author try to wrap his slightly fuddy-duddy sensibility around the digitised, globalised, hyper-mediated core of 21st century wealth and power. The Golden House of the title is a Greek/Colonial revival mansion in an affluent, hermetic corner of Manhattan. Its owner is a shady, ageing, self-proclaimed king of business we know only as Nero Golden, an exile from Mumbai and a classicist who has modelled his family on the empire-builders of antiquity.

His three sons are named after ancient courtiers and mythological heroes, each with a tragic dimension and a markedly modern pathology. Petronius: the autistic, alcoholic, agoraphobic video-game designer. Apuleius: the mystic, socialite artist who finds common cause with the Occupy movement. And Dionysus: their illegitimate half-brother, desperately unsure of his gender and further confused by the surrounding politics.

They are closely observed by their neighbour, and our narrator, a film-maker named Rene who becomes an obvious and sometimes tedious proxy for Rushdie himself. The son of Belgian academics, he is young but old at heart – unversed in technology, a little whiplashed by the speed of change these days, liberal in such a quaint sort of way that he seems almost conservative. Aware that he may be “too deeply immersed in films and books and art”, Rene projects his own imaginings onto what little he knows about the father’s original sin and the brothers’ interpersonal struggles.

Whole sections of the novel are rendered in script form, full of character monologues, lurid gangster-movie flourishes and melodramatic twists, with non-stop references to high and low culture (Euripides, Jay Gatsby, Candy Crush Saga) and cameo appearances by the likes of Mikhail Gorbachev and Werner Herzog.

Between plot points, rhetorical digressions range from “trans, nonbinary, nonconforming” sexuality to the fear of offence that now prevails on university campuses. Rushdie’s mouthpieces make some valid points no doubt, but even thick-skinned readers may be taken aback by his portraits of the Golden boys’ multi-ethnic yet uniformly beautiful female partners – a malevolent Russian gymnast who takes Nero as her “Tsar”, a doomed Somali sculptor, a Swedish-Indian curator of a so-called Museum of Identity.

As his narrative sprawls across the eight years of the Obama presidency, there’s also recurring quasi-cleverness to his scene-setting details, a tendency toward glib shorthand in describing, say, “a Silicon Valley billionaire with a silicon wife.” At the same time, his prose is just as often a pleasure, bursting with colour and texture.

There’s a sense of abundance to his best work that is palpable again here, as he tries to squeeze the whole world between his pages and seems more curious and generous in the attempt than younger modern moralists like Jonathan Franzen.

And if early chapters seem a little weightless, like Gatsby’s silk shirts thrown into the air, the force of our recent history gives the novel a gathering heft. Donald Trump is never mentioned by name, but referred to throughout as The Joker, a giggling cartoon supervillain whose spectre grows throughout the story, bringing Rushdie’s tangential asides on gun deaths, race relations and the state of the union into ominous focus.

“What did anything mean if the worst happened, if the brightness fell from the air, if the lies, the slanders, the ugliness became the face of America?” Rene asks himself. As Nero Golden is gradually exposed and toppled, so is the sustaining myth of the self-made man, and the abiding hope of a better life in the United States.

Uneven as it may be, the result stands as Rushdie’s most vital book in years, and perhaps the first protest novel of the Trump era – a flawed but valid piece of art to be held up against the betrayal and disfigurement of America’s promise, as witnessed by an immigrant, and represented by its president.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here