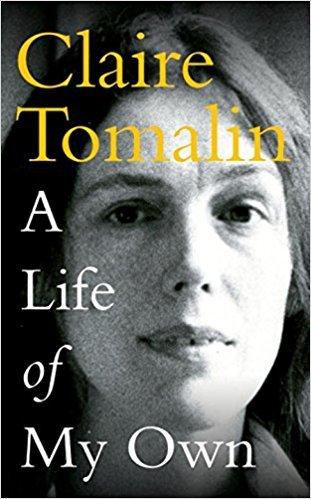

A Life Of My Own

Claire Tomalin

Viking £16.99

Review by Hugh MacDonald

IT is Edinburgh at the dawn of the new millennium, as dreich as only a summer’s Sunday morning in the capital can be. A brisk, confident woman commands the lectern in a tent at the book festival, telling tales of her research into a forthcoming biography of Samuel Pepys.

Claire Tomalin appears at that moment as wholly in command: of her subject, of her life, of herself. She is the acme of a woman at work but at ease. The backstory, though, is at odds with this image. Her biography reveals a life of turmoil, turbulence and genuine, recurring tragedy.

The loss of her husband, Nick, as a result of a missile strike on a car when working as a war correspondent in Israel in 1973, was the most gaudily public of the trials to confront Tomalin. However, A Life Of My Own is marked with other blows, more private, perhaps, but incurring deeper wounds that cannot be salved by thought or time.

There is one strand of Tomalin’s life that is accompanied by achievement and the subsequent applause. There is another that is darker, troubling. They, of course, co-exist.

The successes can be quickly annotated. She achieved a first at Cambridge, was an innovative and brilliant literary editor, particularly at the Sunday Times; she has become one of the most accomplished biographers of her era, chronicling the lives of Dickens, Wollstonecraft, Austen, Hardy and Pepys among others to wonderful effect. This is her professional, public life.

Tomalin, too, had the fleeting, sometimes insubstantial private encounters with others. She had an affair with Martin Amis ("I noticed his hands shook in the morning, making him seem more vulnerable"), subsequently married Michael Frayn, employed both Julian Barnes and Christopher Hitchens as assistants.

She has a series of anecdotes ranging from a naked George Melly doing party tricks to a sleeping Ted Heath at dinner. Saul Bellow congratulated her on her legs, an unconscious nod to the time when a first at Cambridge could put a woman on the path to further education at a secretarial college. Her neighbours as a young married woman included the Attenboroughs, Alan Bennett and his lady in the van.

There is, in passing, a delicious put-down of Andrew Neil, her editor at the Sunday Times. Tomalin and the Scot were not kindred spirits. She applies the stiletto after describing him as a poor editor: “Neil has found his metier since on television.”

This is largely all good fun as the great and the not so good wander in and out of newspaper offices or publishers’ parties.

However, A Life Of My Own has a profound substance and aches with the burden of heavy reflection. Tomalin asserts that she moves “between the trivial and tragic in a way that could seem callous’’. But she adds correctly: “That is how life is.”

So her success at Cambridge is followed by the realisation that she has not the talent to become a poet: “My decision left me with an emptiness in my life which has never quite been filled.”

A marriage to the most glamorous, promising journalist of his era precedes infidelity on both sides, domestic violence inflicted by the husband and desertion, deceit and unhappiness. There are tears, stitches inserted in her mouth and scenes of desperation.

It is a merciless portrait of both Nick Tomalin and of a dysfunctional partnership. She is frank in assessing the relationship after the death of her husband: “I doubted our marriage would have prospered.”

This openness does not extend to the relationship with a sister who disappears from the narrative but otherwise Tomalin is unsparingly honest. As a mother, she lost a son shortly after birth, another son has lived with spina bifida and a daughter committed suicide. This brutal sentence obviously cannot convey the anguish inflicted upon Tomalin.

The writer, though, finds a way to describe the losses, reflect on the blessings, particularly those of Tom, the disabled son, who continues to pursue a fulfilling life. But there is regret, an enduring anguish.

The trivial and the tragic, the witty anecdote and the awful reflection have conspired to produce a beguiling, unsettling and unforgettable biography. There are blemishes. The ending is unsatisfactory, almost as if Tomalin had to reach a word count. Her comments on Brexit and other subjects suggest the desperate, unspoken cry of “are we there yet?” The disappearance of her sister and her mother’s retreat into an almost ghostly presence both deserve further illumination.

But these are quibbles. The acclaim for an outstanding biography extends to a deepening respect, even affection for its author.

Her father tells her as he approaches the end: “You have had a hard life.” This conversation occurs after the publication of the Pepys book that Tomalin memorably heralded in Edinburgh.

She recalls in the memoir the awful surgery Pepys had to endure because of recurring kidney stones. “It makes you think again about what he had gone through in the course of his life, recognise how much pain he had to endure, and admire his courage the more.”

These sentiments apply to his biographer. This is a work that demands Tomalin be self-reflective but she eschews self-pity.

She has lived, loved and lost. She has created a life of her own but one that has an extraordinary reach and resonance beyond the bounds of the deeply, woundingly personal.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here