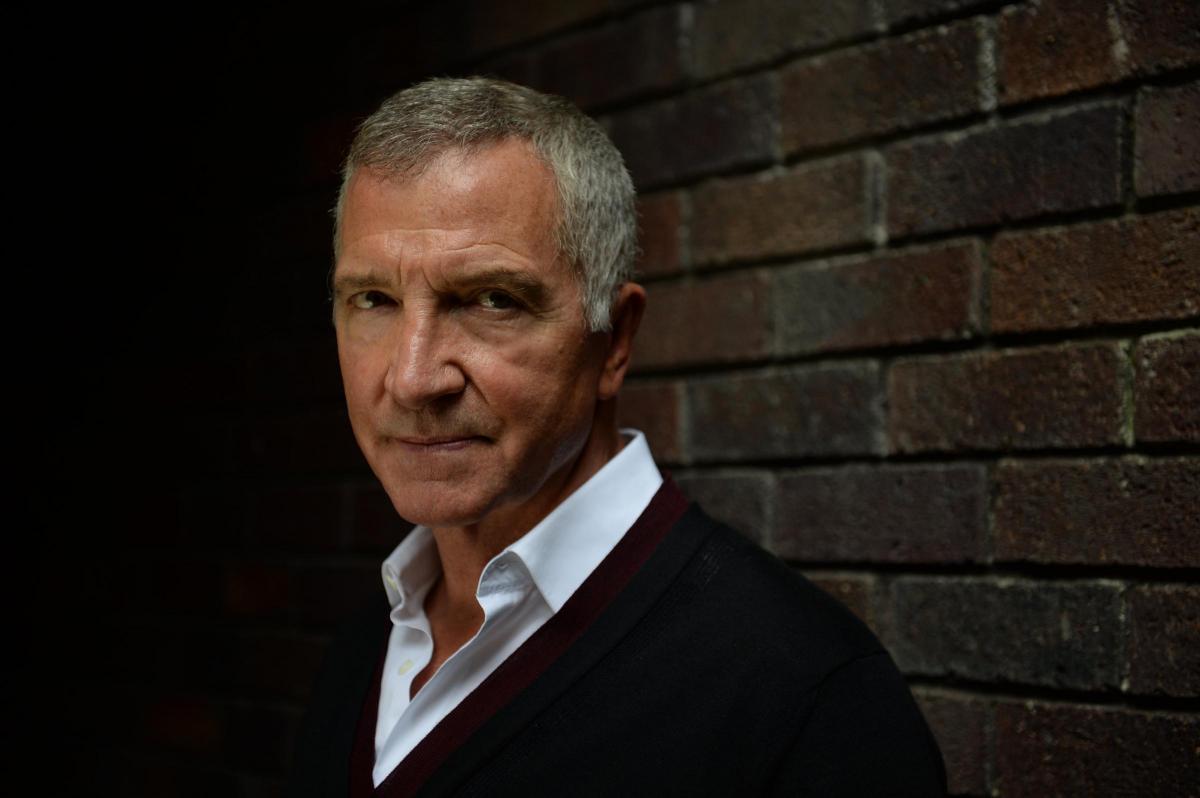

ONCE or maybe twice a week Graeme Souness will dream that he is on a football field in the middle of a game. “I can’t believe it,” he says. “I wake up and I’m not playing and I’m lying in bed and I’m nearly 65.” Even in the twilit tastefulness of the bar in the Dakota Hotel you can see the air of mild astonishment on the face of the man when he says it.

But here we are. Come May next year Souness will reach pensionable age and coincidentally celebrate 50 years, boy and man, in the game of football. Five decades which took him from Edinburgh to Spurs, and Middlesbrough, before conquering Europe with Liverpool, and, then to more success as a manager at Rangers. And now he spends his life telling others in football how they could do it better.

A Glasgow Tuesday. Souness has just come from a signing session for his new book Football: My Life, My Passion. It went on for two hours. There are clearly Rangers fans who remember him fondly, a talisman of better days (48 hours later Rangers manager Pedro Caixinha will get his marching orders).

He’s looking well, halfway into his seventh decade. He’s in the gym five days a week, he says. “And I feel guilty it’s just five.”

Souness was always the ultimate example of footballer as hard man. He was uncompromising on the field and off. Maybe it’s just that he’s tired, but today there’s a softness to him, in his features and his attitude. In our hour together I don’t get the famous Souness stare once.

He even offers the odd compliment. “What age are you – 36, 37?” he asks me at one point. And the rest, Graeme. “Well,” he points out, “the light in here isn’t great.”

What is not missing is the self-belief. Souness was quite simply one of the best footballers of his time. And he knows it too. He always knew it.

“Yeah. I was always – and I have no idea where it came from – a confident boy. And when I look at how I’ve lived my life that’s how I’ve lived it. Nothing’s ever been daunting for me. I think now maybe it’s the spirit of youth.

“They talk about young football managers today. ‘Pochettino, 45, young manager learning.’ I was 33 when I took the Rangers job. The thought of me walking in there now with the same attitude … I couldn’t do it with the same fearlessness. As a young man, totally fearless. As you get older, I suppose, you get a bit more cautious in everything you do. But I’ve always been blessed with self-belief.”

That self-confidence at times could show itself, he admits, “in an arrogance that I don’t apologise for. That was me. I get why people didn’t like me, or don’t like me, because I have an arrogance.”

You’ll own up to that, Graeme? He draws back slightly. “It can be perceived as that, but people who know me wouldn’t say it was. Listen, the other thing I’ve been blessed with is I don’t give a flying … what people think of me. I really don’t.”

Writing the book, he says, reminded him that it was ever thus. Born in 1953, he grew up in an Edinburgh prefab the youngest of three boys. His dad was “a very mild man, a really nice guy” while his mum was gentle. Perhaps his self-confidence comes from being the baby of the family, I suggest.

“I think there’s an element of that. I think being the youngest certainly helped me. Always having that secure family background behind me. The first child is always mollycoddled, the second one not so much and the third … I was meant to be the girl anyway so …"

Hmm, it is difficult to imagine someone who in public seems less in touch with his feminine side. The eminent Scottish journalist Hugh McIlvanney memorably summed him up as “Renoir with a razor blade”. He was both artist and assassin. Infamously in a European game against Dinamo Bucharest in 1984 he broke Lica Movila’s jaw (“in two places” he writes).

“It’s not something I’m terribly proud of,” he says when I bring it up, “but at the end of the day there were people looking to do that to me and my team-mates.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising then that in the days leading up to our conversation I’ve been thinking a lot about the Souness moustache. A sawn-off statement of bristled manliness, it must feature in any taxonomy of British masculinity of the late 1970s. (This may, I concede, have something to do with the fact my dad had a Zapata moustache at the time.)

“A proper moustache,” is Souness’s own approving summation of his lip adornment back then. When did he grow it? “That would have been at Middlesbrough. It was fashionable and fortunately for me I could grow one. And fortunately for me I had naturally curly hair and I never permed it. I got lucky. In my youth fashion was about moustaches and curly hair.”

Ah, footballer chic. Souness was a mixture of the cocksure and peacock (or as peacockish as a footballer could be back then). In his recent book Keegan and Dalglish, the author Richard T Kelly says of Souness: “His avowed personal style was a version of the high life: tastes for cold sancerre, Cardin slacks and the Commodores on the stereo.”

For Kelly, Souness was an atypical Scot – strong-minded, outgoing (unlike Ian Rush he loved playing in Italy for Sampdoria after leaving Liverpool. That said, he also confirms to me that he voted in favour of Brexit).

Dalglish, infamously, was reluctant to share a room with his Liverpool and Scotland team-mate because Souness used a hairdresser and Dalglish thought he might be gay (ah, the 1970s).

Were you a vain man, Graeme? “My wife would say I still am. I certainly was in my younger days.”

How does that manifest itself now? “I buy more clothes than her. I buy more deodorant and perfume than her. But I can get ready in 10 minutes.”

What would Souness the manager make of Souness the player? “I think there’s a very simple way to answer that. I think you look at the people who made me captain of my country, captain of the most successful team in Britain and in Europe. They chose me and there were some other super candidates. I am trying to think … Did I ever get a manager the sack? No.

“I’d want me in my team. I’d want someone like me in my team.”

If Liverpool saw the best of Souness the player, it was Rangers who got the best of Souness as a manager. He arrived in the spring of 1986 as a player-manager, got sent off in his first game, and yet quickly re-established the club as a force in Scottish football. He signed English players, he signed a high-profile Catholic player in Mo Johnston, he reminded Rangers fans what it was like to win the title after an eight-year barren spell.

Did he understand what he was taking on when he went to Ibrox? “I thought I did. That was the team I supported as a kid. I was never a watcher of football because I was playing football for my school in the morning and boys club in the afternoon. But I would have seen maybe 10 European nights at Ibrox.

“I thought I knew about the club. I’ve been a big player. I’ve played for my country. I’m Scottish. I’m bound to know what Rangers is about and there was nothing in my life to prepare me for that job. Rangers, along with Celtic, Liverpool, Man United, is an institution. They’re not football clubs. And it was a far bigger job than anything I could have imagined.

“But then again, it was my first job in management and within a couple of years I was the second largest shareholder and I had more say in everything. In those days it was a fabulous place to be. It was a monster football club firing on all cylinders and going places and we excited every Rangers supporter out there.”

He fell out with everyone along the way of course, from the Scottish Football Association to tea ladies in Perth. And you could argue, of course, that the Souness big-spending template would be the cause of Rangers’ later problems.

But that was still in the future. “We got it right straight away. In the first year we won the league. In five seasons I was there I’m only credited with three titles. I think it was four because I left in March, I think, and we were so far ahead. I really enjoyed myself. I thought every managers’ job is like that … And unfortunately it’s not.”

Souness left Ibrox to take over from his old team-mate Kenny Dalglish at Anfield. And suddenly the rising arc of success took a downturn.

Liverpool wasn’t the club he had left in 1984. It had weathered the tragedies of Heysel and Hillsborough, it was a team that had won the league title the year before. But it hasn’t won one since.

An FA Cup victory in 1992 apart, Souness’s time as Liverpool manager was marked by controversy and indifferent form. You wonder how someone so used to success copes when it suddenly disappears.

“It was hard because I couldn’t understand why the people I worked with didn’t share my passion. I made mistakes, but what I would say is you don’t get a job because everything’s right at the club.

“It was an old team, it needed major changes, it needed rebuilding and that’s what I was told by the chief executive.”

He let ageing players go before getting replacements in, which he now admits wasn’t clever. And he shouldn’t have got involved in sorting out contracts. It meant veterans such as Ian Rush and Ronnie Whelan were coming to him asking why the new signings were getting more money than they were.

“If I had been them I’d have been exactly the same,” Souness says. “I had to say to them: ‘Sorry, you signed a deal two years ago. That’s the way the transfer fees, the way salaries have gone.’ So I’m saying no to them on a Wednesday or a Thursday and on Saturday I’m saying: ‘Come on, give me everything.’”

It worked for you at Rangers. “Well, there were no legends like Rushie and Ronnie Whelan.”

During his time at Anfield there were also health issues, which led to what he calls his greatest mistake. In 1992 Souness required open heart surgery. In its wake he agreed to be photographed by the Sun newspaper in his hospital bed being kissed by his then girlfriend.

Unfortunately the photograph appeared on the anniversary of the Hillsborough tragedy, a fact that did not go down well in a city that remembered the paper’s deceitful Hillsborough front page emblazoned with the headline “The Truth”.

“The article in the Sun is my single biggest regret in life, never mind football,” Souness says. "I know how it upset many people and I know that people will never forgive me. I have to live with that and I do.”

He points out that players were doing articles with the paper at the time. But, he adds, “I shouldn’t have dealt with them in the first place. So that’s a deep regret.”

In the wake of his heart op Souness was for a while a shadow of his former self. He felt vulnerable. He would find himself crying for no reason. He was suddenly faced with his own mortality. For someone normally so self-confident, so assured in life, how did that hit him?

“It takes some accepting. It’s a realisation. But what can you do? You just have to say: ‘Yeah, It’s happened to me.' It took me a year to get back. In that period I could be quite emotional at times for no obvious reason. There’d be tears in your eyes. You say to yourself: ‘Why are you feeling like this?' And you couldn’t answer it.”

Was football any help at that point? “Not really, because it wasn’t going well.” He's had problems since then, including a minor heart operation in 2015.

Souness thinks now he should have resigned from Liverpool when he had his surgery in 1992. But he kept going until January 1994. Other management jobs followed, some good (Blackburn), some not so much (he lasted four months at Torino).

His last management job was at Newcastle United. He seems to have spent most of his time there arguing with Craig Bellamy.

“If there’s something I’m not happy with I have to say that. The modern way is not that. You’ve got players who earn so much money today it is a case of the tail wagging the dog in football.

“I go into a dressing room and fall out with a player, or six or seven, they collectively might be worth 200 million quid. You lose a game, that old chestnut comes out. The agent phones up the chief exec or the owner and says: ‘You know he’s lost the dressing room,’ and the manager is away.”

(NB: falling out with six or seven players in a dressing room might suggest that you have lost the dressing room, but we'll let that lie.)

The world has changed. The game in the English Premier League is thriving and the rewards are concomitant. “At Liverpool in 1984 I got £125,000 [a year] which at that time equated to 12 times the average man’s wage. And there are players today in England earning 300 grand a week, which, if the average man’s wage is £25,000, that equates to how many times? Six hundred.”

Does he miss anything from being in at the sharp end? “I’ll go to games and I’ll be on the touchline thinking: ‘What would I do there? How would I make the change there?’ It lasts a millisecond and then you think of the guys who’ve lost 3-0, 4-0.

“I wasn’t someone who could leave the problems at the training ground or the stadium. I brought them back with me and it manifested itself in me being very quiet. I’m not a shouter because all the time I was thinking of the issues I had to deal with.

“If we were out for dinner with our pals and there was a lull in the conversation or in the bar I started to drift off to the issues I’ve got. And I think I’m a better person for not being involved in it.”

What did you sacrifice for football?

“What did I sacrifice? I was selfish in management. I think of part of my life with my second wife. She only had the aggro years, the years of management. She didn’t know me as a player. Maybe I should have not gone on in management as long as I did for her sake. It was difficult on her as well so maybe I was a bit selfish in that respect.”

Souness’s personal life is largely missing from his new book. He’s been married twice, has four children and three stepchildren. He married Karen in 1994 in Las Vegas.

Was Elvis involved? “It was a very lovely lady minister. It was very nice. There was nothing tacky about it.”

Away from football, is there a hinterland? “I like my wines. Red super Tuscans and white burgundies. That’s an indulgence of mine. I do buy expensive wine. Never been a gambler. Spend too much money on clothes.

“What else is there? Took up golf eight years ago and at this moment in time I’m trying to persuade my wife we should buy a place abroad and spend more time abroad because our son has just gone to university, so we have the freedom to move about a bit more and the job allows us to do that as well.”

Is he reconciled to the fact he will be 65 on his next birthday? “No. I still think the best years are ahead. I don’t know where that comes from. I know if I think about it too much that it can’t be true. But I think I’ve got some great years ahead, please God.

“I want to try to be around as long as I can for my young boy who’s 18, because life’s been fantastic so far.”

It’s been a life well lived, then. “Oh f***, yeah. I’d go and do it all again, mistakes and all. As hard as they are to accept at times I’d do it all again.”

When did the moustache go in the end? “When my wife told me to get it off. When it would have been, I can’t remember. It’s never made a comeback. She said: 'Get it off,' and it was off. I’m an obliging husband. I do as I’m told.”

That’s hard to believe, Graeme.

“I’m a pussycat at home.”

Football: My Life, My Passion by Graeme Souness with Douglas Alexander is published by Headline, priced £20

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel