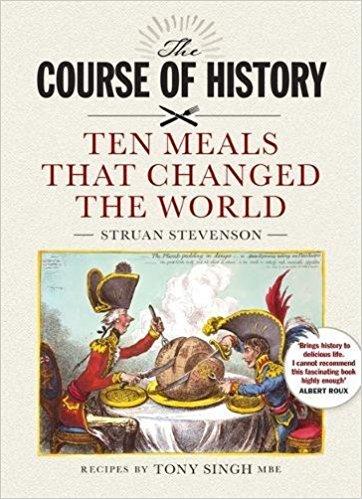

The Course of History: Ten Meals That Changed the World

Struan Stevenson

Birlinn, £16.99

STRUAN Stevenson is a former Conservative member for Scotland in the European Parliament. Of the ten meals that he believes changed the world, eight of them took place in the West and the other two – Churchill’s birthday banquet in Tehran, Nixon in China – were at the West’s instigation. There are no religious meals included despite the fact that “the last Supper and Jesus’ betrayal” get a mention in the introduction. Perhaps this is because the book depends on the substantial rather than the transubstantial to make it work. Whatever significance was bestowed on them later, bread and wine do not require much of a recipe.

Waiting in the wings is Scottish chef Tony Singh who, among many other claims to fame, introduced Kentucky fried rabbit to the BBC’s Great British Menu. While Stevenson makes a case for the power of “dining diplomacy” to shape history, it is Singh’s job “to refashion each recipe into an accessibly modern style, so that you can bring history to life in your own kitchen.” Some of the meals are based on historic records while others reproduce “the dishes that most likely were consumed.”

The first meal that Stevenson considers is Bonnie Prince Charlie’s on the eve of the Battle of Culloden. The meal was hosted in Culloden House and washed down with copious amounts of wine in anticipation of the coming victory. The actual outcome was, of course, bloody defeat and this is a bit of a problem for the book, at least as far as the stimulation of appetite is concerned.

Stevenson doesn’t hold back in his description of the conduct of the battle and the subsequent bloodlust. Early on, a cannonball decapitates one of Charles’s grooms. Later the Hanoverian troops behead and butcher the enemy before “setting off for Inverness, raping and ransacking in a savage and uncontrollable rage.” From here the reader in invited to proceed to the kitchen and prepare a menu that includes Mussel Brose, Rack of Lamb and Cream Crowdie. For the latter, the instruction to “lightly brown oats in a pan over a medium heat until a light brown colour with a lovely nutty aroma” has suddenly lost its allure. Similarly, the process of cooking a rack of lamb is haunted by an earlier description of English dragoons discovering thirty Jacobites in a barn and setting it alight “burning alive all the men inside.”

The prospect of preparing and eating the meal that Hitler offered to Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg while demanding that he surrender his country’s independence is not much more enticing. Hitler was a vegetarian whose lunch might consist of barley broth, semolina noodles and egg and green salad. He boasted of being a teetotaller though Stevenson says that he partook of an occasional cognac or Schnapps. The menu reproduced here follows Hitler’s diet and throws in some pork sausages and sauerkraut for his reluctant guest’s benefit. It’s hard to imagine that anyone would want to bring history to life in their kitchen by reproducing such a meal and remembering its host. It’s even harder to imagine mustering a quorum for the occasion. Hitler was at least able to command the presence of Martin Bormann, Joachim von Ribbentrop and sundry unfortunate Austrians.

Elsewhere you can enjoy Capon stuffed with Virginia ham in the imagined company of Hamilton, Madison and Jefferson discussing where to site the capital of the new United States or discover Russian Caviar before the Congress of Vienna. Scotland hosted its second meal that changed the world when the executives from the four largest oil companies washed up at Achnacarry Castle in 1928 to feast on grouse and venison and discuss cartels and price fixing.

Stevenson has written courageously in the past about Iran and Iraq and outrageously about green energy, but it has hard to understand how “meals” fits his portfolio. His style verges on the wikipedic and the occasional rhetorical flourish doesn’t always go well, creating sentences like “Hamilton’s spoon, heaped with Baked Alaska pudding, hesitated on the way to his lips.” The book raises numerous questions including why most of the world is excluded from it, why there’s no place for spiritual sustenance and whether preserving one monarchy at the expense of another can truly be said to have changed the world. But perhaps that’s taking it too seriously. A quick Google search reveals that the “Ten Meals That Changed the World” is already part of Stevenson’s profile on the Cruise Ship Enrichment website. Its peculiar mix of persecution and pudding might be more palatable on the high seas, though one still fears for the passengers and the destabilising effects of stormy waters.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here