A View of the Empire at Sunset

by Caryl Phillips

Vintage £9.99

Review by Todd McEwen

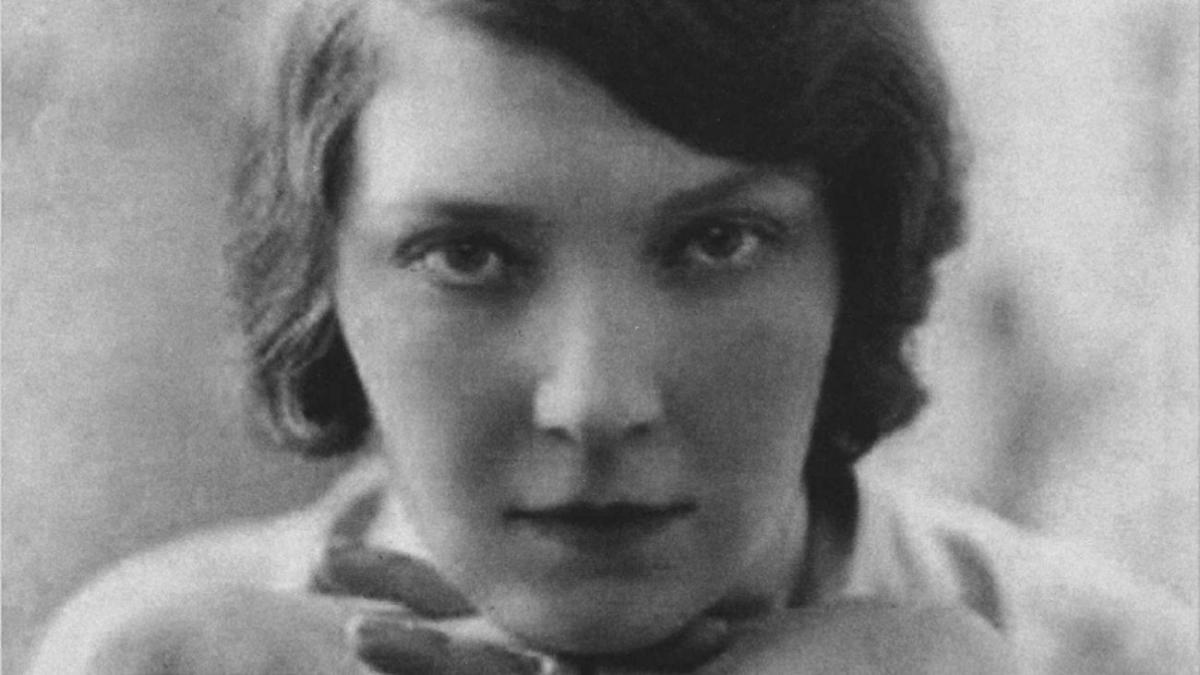

The novelist Jean Rhys, born Ella Gwendolyn Williams in the Caribbean in 1890, was sent to England at the age of 16. Under the thumb of one of those aunts that everybody seemed to have then, she wasn’t impressed. From the start of A View of the Empire at Sunset, Caryl Phillips’s odd rehearsal of Rhys’s life in novel form, she appears as a woman who just naturally baffled people. Something in her looks and demeanour drove people in authority slightly crazy. But there was nothing overtly rebellious about this girl. When she was upset about something, she would climb a tree and sit there for hours. Lots of people do that.

Her mother, a hopeless neurotic, struggled to hold herself and her children above the Negroes, for whom she had great contempt. Her father was the chief medical officer in Dominica, a heavy drinker, and gossiped about. He was Welsh, with disdain for the growing English population there. ‘Gwennie’, as she was called, became a regular at the island’s new Carnegie library. One day the librarian told her an English ‘lady novelist’ was going to visit the island.

As an avid reader (whose urge to write, though, was still nascent), Gwennie attended this event. The woman turned out to be an upholstered bore, worse than that, a poet, reading stuff from the bottom of the drawer. Her father had predicted exactly this: “she wondered how on earth her father had managed so quickly to understand the truth about this woman without ever setting eyes upon her.” Dr Williams seems to have been possessed of a certain sly prescience about things, which he might have passed on to his daughter.

Mocked at her Cambridge school, she leaves for the theatrical life. She has a couple of showgirl pals, hardly dedicated to their art, but using it as a way to get husbands of some description. One of them cautions Gwennie about her attitude to men, echoing the taunts that plagued her through her first two decades: “‘You’ve got to stop pretending you’re a virgin, as that frightens them off. And you always look half-asleep, has anyone told you that?’” Phillips surmises that “Eventually she began to think of herself as not only a strange bird but a bird with a broken wing.”

Gwennie is a romantic, wanting to find what passion and love are. But because she is unsure how to take in her new environment, and worries London with her looks, behaviour and odd way of talking, she handles every encounter by saying almost nothing. This might have added to her small store of mystique, but it also contributed to the exasperation people felt in her presence.

There were always these men hanging around stage doors. Rhys went out with some of them, and it wasn’t good; usually “a bout of inelegant kissing”. What Phillips give us is not so much the story of Jean Rhys, the writer, as of the girl who wanted to become a woman, to discover what that was, and then to become the writer Jean Rhys. She’s impatient to blossom, almost willing it. Shortly before she left the island, she examined herself: “confident that nobody could see her, she rubbed a hand across her chest and once again made sure she was finally budding.”

Whatever it was about Jean Rhys that caught people, and especially men, off-balance, it stayed with her for her entire existence. Phillips imagines her third husband’s thoughts: “He assumes it is the exotic part of her nature that contributes to her allure, but in some rural parts of England she might well be taken for the slow girl in the village. Her eyes, for instance, are perhaps a little too close together, and he often observes her sitting perfectly still in a trancelike state of wonderment, with her lips slightly parted.” But he was just another of the men who never got beyond her looks. One suspects Phillips hasn’t either.

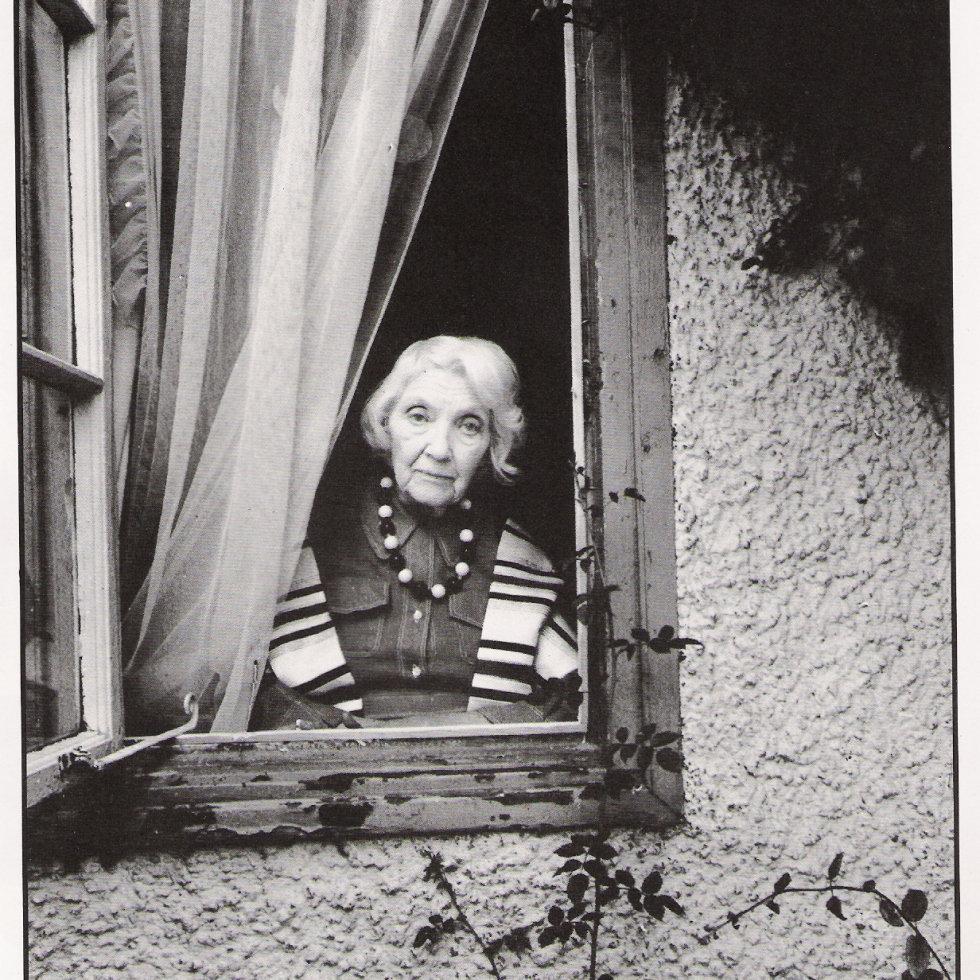

Is isolation one source of the troubled tone of her work? It is never as self-indulgent as many of the narratives of hurt we are now used to. Her life was a constant cycle of rude inquiry, being rebuffed, summed up, and turned into something other in her fiction.

It’s curious that the ‘plot’ of this book, from her childhood through three marriages to totally unsatisfactory, unsatisfying men, makes no place for her life as a writer. Although her second husband was an editor who helped get some early work published, we never experience any of her thoughts about her work or her ambitions for it, and no mention is made of the writers who championed her.

There are infelicities in Phillips’s writing that are not to be found in hers: anachronisms, repetitions, a jumble of tenses and split infinitives, and it’s often difficult even to tell who is speaking. He’s a fierce man for the adjective: why would you describe flowerpots as “curved”?

Reticent, shy, aloof, frightened and pitiably alcoholic as she may have been, it’s hard to square the Jean Rhys that Phillips gives us with the feeling, intelligence and insight displayed in her work. One of the points she made in her novels was that women never get the chance to exist, much. Phillips has dangled her in front of us, but in doing so he’s prevented her interacting with her own life. So we learn very little.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here