LAST November, Time Out New York listed the 50 best documentaries of all time. It is a formidable list, covering every subject under the sun, from the Holocaust (Shoah, Night And Fog) to global warming (An Inconvenient Truth) via music (Gimme Shelter, Woodstock) and the Ali-Foreman “Rumble in the Jungle” (When We Were Kings).

Glasgow Film Festival, which is currently underway, is screening several documentaries in its Stranger Than Fiction strand. That, and the strong contenders in the documentary categories of both the BAFTAs and next Sunday’s Oscars suggest the documentary is in robust health. Meanwhile, the Scottish Documentary Institute, created 15 years ago to stimulate creative documentary through training schemes for directors and producers – is bearing fruit, according to Professor Noémie Mendelle, Director of the Scottish Documentary Institute at Edinburgh College of Art.

"It’s almost as if all the seeds that were planted 15 years ago are starting to bloom now,” she says. “That is really exciting, because we are no longer talking about factual programming, but very much about creative documentary, and this is why it’s successful: it is being made by storytellers, not journalists.

“The whole idea of bringing documentary into cinemas and festivals is in order to be part of the world of storytelling. The documentary is looking extremely healthy in terms of creative talent. It’s exciting: at long last we are seeing what we hoped for, and dreamt of, a couple of generations back.”

Turbulence on the world political stage can draw the interest of documentary-makers but, says Mendelle, “documentaries go beyond the quick headline, and create contexts for the stories they tell. There is a real kind of need from the audience point of view to be able to spend time with, for example, refugees [the subject of Spectres Are Haunting Europe, below], to experience them, to discover their world through their eyes – not just to see what is being presented to the audience about the news.

“That ability to go in-depth – not just factually, but emotionally too – is really what is making those documentaries so attractive.”

However, she adds, the financial side of documentaries “faces really dark days ahead. Most of the films we are talking about are the kind that can only be commissioned or financed to co-production level, which requires funding from our neighbouring countries. more often than not. But all of that is being questioned right now. We don’t know how we will be able to work in the future once Brexit happens. And broadcasters in the UK are diminishing their factual-programming budgets quite dramatically.”

Here, we look at some of the documentaries on show at the Glasgow Film Festival.

I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO (2016)

THERE’S a powerful, startling, line near the end of this riveting documentary, which is based on the words of writer James Baldwin. He is on television, speaking about the state of race relations in America at that time, the 1960s. “There are days, and this is one of them,” he says, “when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it. How precisely you are going to reconcile yourself to your situation here and how you are going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here.”

I Am Not Your Negro, which is directed by Raoul Peck, is a remarkable piece of work, and is a vivid reminder why Baldwin – so articulate, so fearless – is revered by so many people today, at a time of Black Lives Matter.

In the summer of 1969, Baldwin wrote to his agent from the south of France, suggesting a book about the story of America through his relationships with civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Baldwin had been friends with all, but he had also had to mourn their deaths: Evers had been murdered in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, King in 1968.

They were all, he said, “very different men … I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other as, in truth, they did, and use their dreadful journey as a means of instructing the people whom they loved so much, who betrayed them and for whom they gave their lives”.

A mere 30 pages of notes for the book, Remember This House, had been completed by the time of Baldwin’s death in 1987, but it, along with other selections from his inimitable prose, forms the basis of this riveting, Oscar-nominated documentary.

His words are voiced here by Samuel L Jackson, but there is plenty of footage of Baldwin – on television, at a Cambridge University debate. There is footage, too, of civil-rights marches, of white cops dealing uncompromisingly (and sometimes brutally) with them, and of angry whites resisting integration.

As the Washington Post observed recently: “Peck has used an unfinished manuscript by Baldwin not just as a way to explore the evolving psyche of one of America’s pre-eminent mid-20th-century men of letters, but also as a springboard to explore how racism, identity, history and collective denial and shame have conspired to forge a dramatically bifurcated American culture.”

Baldwin recalls that day in 1957 when he saw those wrenching photographs of Dorothy Counts, a black, 15-year-old schoolgirl, “being reviled and spat upon” by a jeering white mob as she bravely made her way to a school in Charlotte, North Carolina. One infamous photograph shows a white boy making devil’s horns behind Dorothy’s head. Baldwin was in Paris at the time; the photographs made him angry and ashamed. He knew then that he had to leave France and return home to America.

The documentary also has Baldwin analysing the way in which black people were frequently portrayed in films and advertising. “The story of the Negro in America is the story of America,” he says, via Jackson, at one point. “It is not a pretty story.”

Peck has also updated the story to highlight the killings in recent years of young black people – Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Aiyana Stanley-Jones – to illustrate, in the words of one critic, how Baldwin’s words echo with equal urgency today.

In the same TV segment mentioned earlier, Baldwin says flatly that he is terrified at the “moral apathy, the death of the heart” happening in his country. “These people have deluded themselves for so long, they really don’t think I’m human.”

I Am Not Your Negro screens at the GFT on Wednesday, Feb 22 at 6pm. The screening is sponsored by the Sunday Herald. The film is on general cinema release from April 7

SPECTRES ARE HAUNTING EUROPE (2016)

IN late May of last year, police in Greece began the process of clearing some 8,500 residents from Idomeni, Europe’s largest refugee camp. Some 400 riot police entered at dawn on May 24; by the time darkness fell, some 2,000 had been bussed to government-run camps.

The Greece-Macedonia border had been shut in March, leaving thousands of people stranded. Many had come from such conflict zones as Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

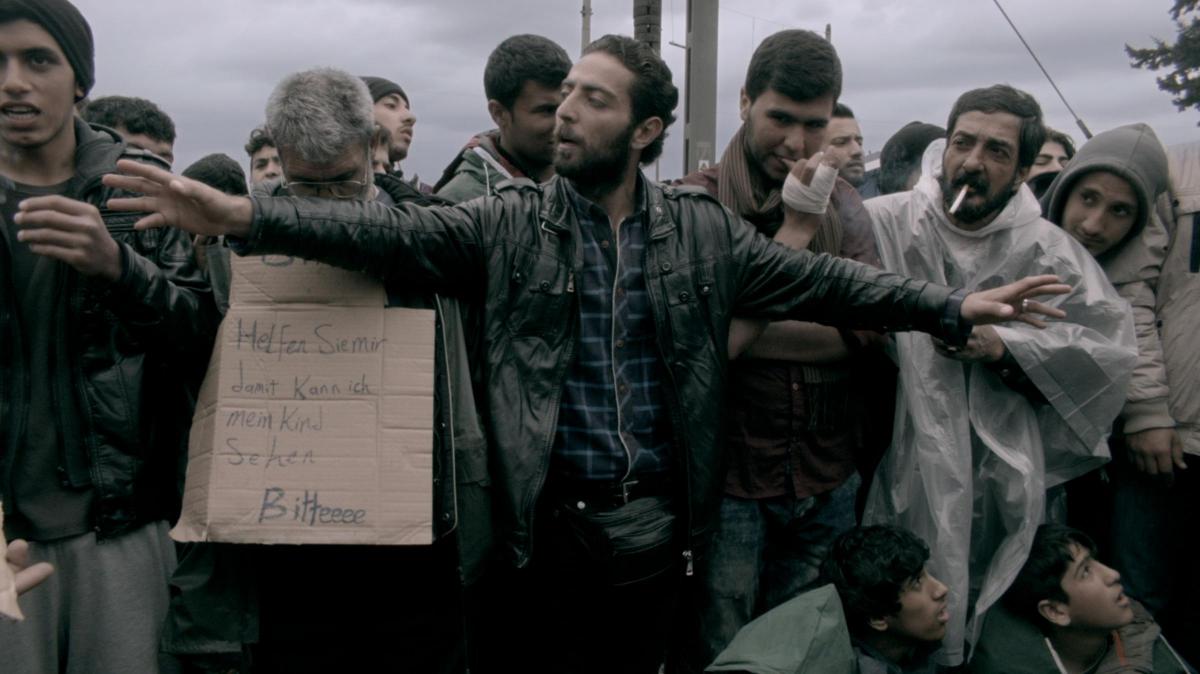

When Europe decided to close its borders that March, Idomeni’s “residents” decided to occupy the nearby train tracks, thus disrupting the trains that ferried goods across the border. This quietly captivating documentary captures that protest in detail.

“Minimalist” is one word that has been used to describe Spectres Are Haunting Europe, the work of Maria Kourkouta and Niki Giannari. It has no commentary (subtitles are provided in English); visually, there is a long series of shots in which the camera remains static, for minutes at a time. People cross in front of the camera, many of them clutching bags and luggage, or with children in tow. There are shots of people queuing patiently, only their legs and feet visible, often in the mud and the rain. Children’s voices, and the hum of everyday conversation, gently fill the soundtrack.

At one point there’s an impassioned debate about the occupation of the train tracks, and about what Greece has done for the refugees. One man, insistent, protests: “We are losing ourselves, we are losing our children, our health and everything! … We only came here to pass to Germany.” Another man, a fourth-year law student who had been one of thousands to escape from Daesh, says he has “lost everything to come here and I won’t move an inch”. Tannoy announcements had made it clear that the Greek border with Macedonia was now closed and that the Greek authorities would take the residents to reception centres, where food, medical attention and accommodation awaited.

Spectres Are Haunting Europe deservedly won the Best International Documentary Film award at the 20th Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival in the Czech Republic. It is a sympathetic and meditative depiction of the faceless but determined people who uprooted themselves and their families to make the perilous journey to Europe in order to find sanctuary, and a better life.

* GFT, Feb 25, 3.15pm

THE CHOCOLATE CASE (2016)

TEUN van der Keuken, a journalist on Dutch TV’s Consumers Investigation Agency (CIA), discovered the extent of child slave labour in the chocolate industry, with young children in Africa working in appalling conditions. He had the idea of trying to get himself prosecuted in Holland for, in the words of the lawyer he enlisted, being guilty of “fencing, by eating chocolate made from cocoa produced with the use of forced labour”.

It raised the prospect, if successful, of criminalising millions of people who bought and ate chocolate. But would van der Keuken’s word on its own be enough to land him in court?

Benthe Forrer’s documentary, however, widens its focus to look at the TV team’s efforts to devise a slavery-free chocolate bar – initially as a stunt. Remarkably, given that they were journalists and not entrepreneurs, they actually succeeded in making a go of it, even if the process was an exacting one.

The deeper the documentary wades into the issues, the more engrossing it becomes. The child-slavery issue is handled sensitively, and is enough to make you think twice before eating chocolate. During the team’s initial investigations, several years ago, the PR head at one giant chocolate company tells van der Keuken by phone: “For a poor farmer in Africa, often the help that he gets from his children is vital in order to maintain the standard of living of the family. What’s wrong with that?” He affirms that child labour exists, and adds: “Let’s face it, slavery exists. Clearly.”

* CCA, today (Feb 19) (3.45pm).

The Glasgow Film Festival continues until February 26. www.glasgowfilm.org/festival#gff17

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here