This week, the acclaimed novelist James Robertson hosts a Celtic Connections celebration of the life of his great friend, the musician Michael Marra. The event shares a title with Robertson's latest book, Arrest This Moment – an affectionate tribute that includes interviews with Marra's friends and family and an imaginary conversation with the late musician. In this exclusive extract, he explains the thinking behind his unconventional biography, begins conversing with his friend, sheds new light on one of Marra's songs and shares insights from some of those who knew him best.

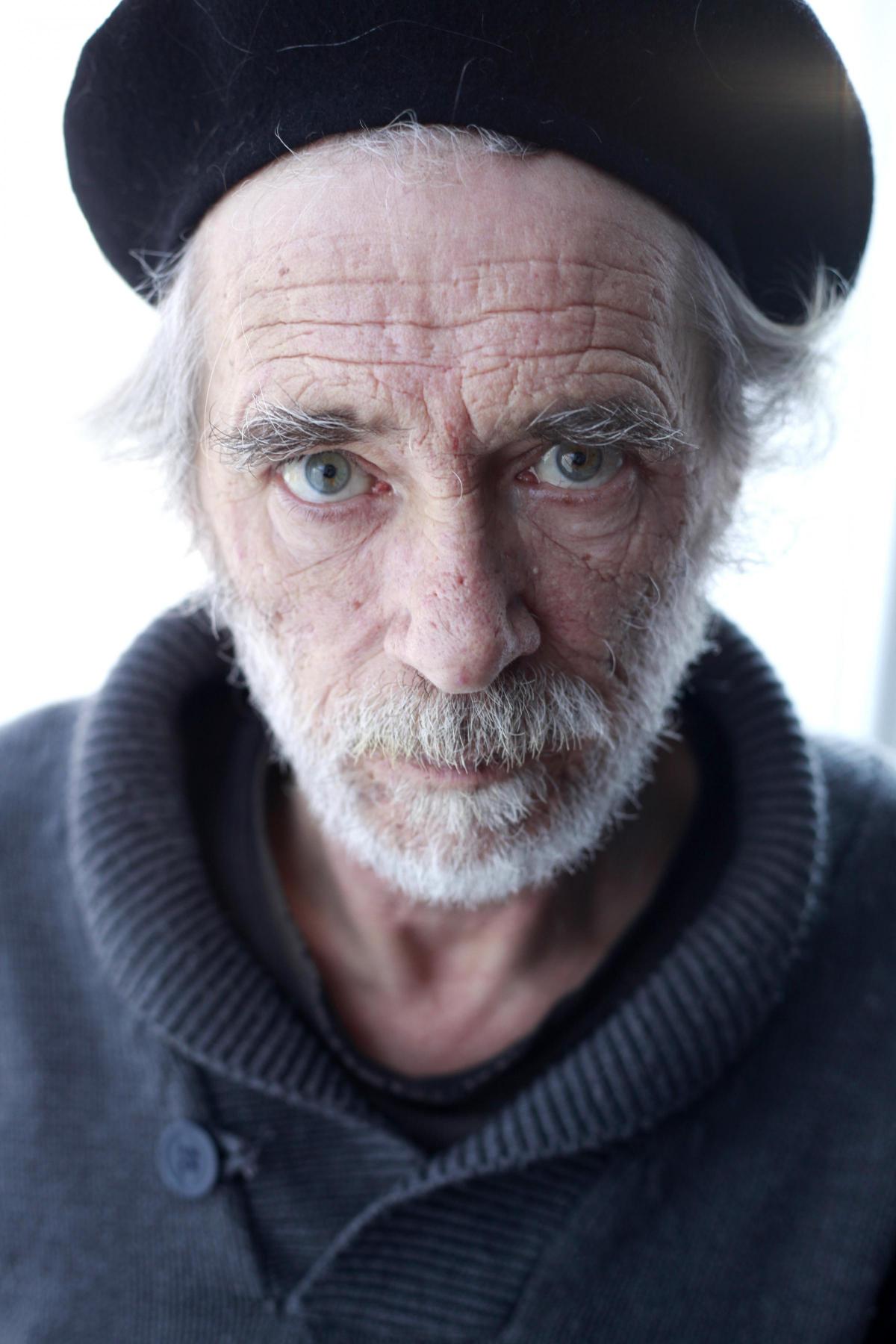

IN the pantry next to our kitchen hangs a large photograph of Michael Marra. It is one of a series taken by participants in a masterclass run by Calum Colvin, whose portrait of Michael, now in the McManus Art Gallery in Dundee, is reproduced on the cover of my book, Michael Marra: Arrest This Moment. Michael is sitting on a stool, hands resting on thighs, with his beret pushed back from his brow and his head turned towards something or somebody off-camera, to his right. It’s a fine picture, capturing as it does the resignation of a man who doesn’t like to pose.

With the pantry door closed, a stranger to the house wouldn’t know that Michael is behind it. Often, though, the door lies open, and then it seems, looking at him, as if he is listening to whatever conversation is going on in the kitchen. But whether the door is open or closed really makes no difference: he is still there. It is amazing how much he is still there.

Michael and I spent a lot of hours sitting on either side of the kitchen table, talking. He could make a cup of black coffee last a very long time. I wish now I could remember all the things he told me across that table. I can’t, but I do remember a lot.

During the summer of 2016, I worked my way through a box of photographs, theatre programmes, scrapbooks and other miscellanea amassed by his wife Peggy, as I tried to find a way into telling Michael’s story. I had been trying for a while. To begin at the beginning and follow a chronological line from there might have been the obvious route but it didn’t seem to fit with the kind of man he was. “Obvious” isn’t the first word that comes to mind to describe Michael. Clear, coherent, audible, unmistakable, distinctive – all of those, yes. But Michael Marra, obvious? I don’t think so. So I began to wonder how he would do it. Where would he start, if it was down to him to make sense of that accumulation of memories? Possibly by saying it was not a project that interested him or one in which he wanted to invest any of his energy.

After he died his family were united in their opinions of how he would have felt about the outpouring of tributes and appreciations of him as a songwriter, performer and person. “Horrified”, his wife Peggy said. “Mortified”, “highly embarrassed”, his daughter Alice and son Matthew were sure. “He would have winced,” his older brother Nicky said. “Double-winced,” his sister Mary added. Or, as his younger brother Chris put it, it would have been “a pure minter”. So maybe he would tell me he had better, more important things to do with his time than tell his own story.

Then I might reply: “But it’s not your time, Michael, it’s mine.” And he would stop and consider that. Thinking of it as somebody else’s project, he would want to make some observations, even offer some help. Because he was that kind of man: considering, considerate, thoughtful, observant, helpful. He would want the thing to work, for the other person.

I was also, for reasons largely beyond my control, way behind schedule. Michael would have understood. Running late? He could easily have advised slowing down, or even stopping and going back a few stages. He had a good appreciation of effort and attention to detail. He understood that some jobs take more time than you thought was available. “The apple will fall when the tree is ready,” he said once, when asked when the next album was coming out. He always wanted to get things right. More than once he told me, “If it’s easy, it’s probably not worth doing.” Which is a sentence containing reassurance and discouragement in equal measure: the sort of formula Dundonians pride themselves on. And Michael, to the marrow, was a Dundonian.

Already I found I was talking to him and he was talking to me, and not for the first time since he left us. When he was alive, the prelude to such a conversation would be a phone call. “Hello. James?” The unmistakable gravel of his voice. “It’s Michael.” As if it could be anybody else. “Are you working?” (He expected you to be.) “Do you have time for a chat? Good. I’ll come round.” By the time I’d made the coffee, round he would have come. And we would go from there.

I wanted to ask Michael about songwriting, about where the songs came from, how they ended up in the form they did. And I wanted to ask him about where he came from. Origins and outcomes. It seemed to me that these things must be connected. Actually, that was just a pretext. What I really wanted was to hear his voice again.

I thought I caught him

glancing quickly away when I went into the pantry for something. I didn’t close the door behind me.

James: You decided early on that you wanted to write songs. How did you know that?

Michael: Music was always very important in our home when I was a boy. We all loved listening to it and playing it. I was curious, even when I was six or seven, about how it was made. May I ask why that photograph of me is in there?

J: It felt appropriate. It’s right behind where you used to sit.

M: I used to sit here in the kitchen.

Now I’m in a cupboard. Where it can

be quite dark.

J: It’s not a cupboard, it’s a room. It’s called a ‘butler’s pantry’.

M: A butler? You are not selling this well.

J: Think of it as a metaphor. That thing you used to say about having your name in brackets. About being behind the scenes, off-stage, and everybody else singing your songs.

M: You probably didn’t catch that.

J: Catch what?

M: My wry chuckle. It’s true, though, I didn’t know what Burt Bacharach looked like until I was in my 20s. I liked that, the idea of the song speaking for itself, the writer being invisible.

REINTERPRETING MOTHER GLASGOW

When Pat Kane saw [Michael Marra’s collaborative theatre production] A Wee Home From Home at the Tron Theatre, he sent Michael, by letter, an incisive analysis of the show, and asked him for the tune and lyrics of Mother Glasgow. The song was a huge success for the Kane brothers’ band Hue And Cry when they released it on their 1989 Bitter Suite album. But Michael was conflicted about the way Pat Kane changed the phrasing and tenor of the song, effectively reinterpreting its deeply critical take on the sectarian divide in Glasgow. In an interview with David Belcher a couple of years later he admitted as much:

“It’s become I Belong To Mother Glasgow. It worked on the show and made sense when A Wee Home From Home was on the telly near Christmas. On the telly you had violent images of Orange bands, a wine bottle smashing on a fence, the Union Jack in the colours of the Irish tricolour. Pat Kane sings it so beautifully, and I’m very grateful to him, but that song confuses me now. The danger’s in the tune … It’s a bit seductive.”

He elaborated on this theme elsewhere: “It is not a song that says ‘I love Glasgow, it’s a nice place’. It’s a complaint, it’s a song about the wonderful gift of communication that Glaswegians have that’s been twisted and I still hear educated people coming away with this bigotry that you just don’t get in our part of the country, but I hear it often in Glasgow. It makes you feel ill. And Mother Glasgow is about that, the waste of great communication.”

THE MICHAEL MARRA WE KNEW

Liz Lochhead, poet

“He was a one-off. He turned everything upside down and made you see it differently. His way of looking at things was so exciting and illuminating – even if he revealed it just by an off-the-cuff remark or a wee joke. He changed me in ways that nobody could change him. Once you had known Michael, you wanted to conduct your own life as much as possible as he conducted his, with that quiet confidence in his own brand of integrity. An awful lot of people who knew Michael became better people because of knowing him.”

Rab Noakes, musician

“It can’t be underestimated how unique Michael was. You can sing Michael’s songs – I put Guernsey Kitchen Porter onto my latest album and Niel Gow’s Apprentice on an album I did in the early 1990s, so you can find a way into the songs – but you’re not going to catch the same things that Michael Marra did. He’s inimitable in that sense. And he has no successor either.”

Alice Marra, daughter and musician

“For somebody who didn’t go to school that much, he knew an amazing amount. When you’re little you think that your dad knows everything – everybody thinks that about their dad – but I remember having conversations with friends when somebody would say, my dad knows everything, and I would be thinking, no, but my dad really does know everything. Anything you asked him, he had an answer. We did a lot of quizzes, that was always a big thing in the evenings, the four of us with a quiz book, and he would get every single question right.

“People imagine we must have grown up in a house which was constantly full of music, but it wasn’t like that. When he finished working, he didn’t want more music. When he came out of his room he wanted to watch TV. But I do remember one time when I had Kylie on really loud, he said, one day you’ll find Joni Mitchell and everything will be OK. And I did!”

Karine Polwart, musician

“Michael had a songwriter’s voice like no other. And I’m not talking about the gorgeous gravelly sound he made when he opened his mouth but about his eye and his ear for people and place and particularity. There’s such humanity to Michael’s songs, even when he’s writing for laughs. He’s expert at satire but doesn’t sneer. Baps And Paste is one of the funniest songs I’ve ever heard but I never for a minute think Michael’s being cruel. He’s just got it. And that’s maybe part of why he is so loved in his own city.

“There’s a beautiful quote attributed to Woody Guthrie that says: ‘I hate a song that makes you think you are not any good. I hate a song that makes you think that you are just born to lose. Bound to lose. No good to nobody. No good for nothing.’

“I reckon Michael held that in his heart as a writer too, because it’s his humility and his humour and his humanity above all else that distinguish him.”

Alice and Chris Marra, Rab Noakes, Karine Polwart and others will join James Robertson at Arrest This Moment: Celebrating The Life Of Michael Marra In Words And Pictures at the Pavilion Theatre, Glasgow on Thursday, February 1 at 7.30pm as part of Celtic Connections. The Sunday Herald is the festival’s media partner. For tickets and full programme details visit www.celticconnections.com

James Robertson and Liz Lochhead will also be present a celebration of the life of Michael Marra at Glasgow’s Aye Write! festival on March 16 www.ayewrite.com

Arrest This Moment is published

by Big Sky, £16.99

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here