Malcolm Higgins

Two years ago, a doormat went missing from an unremarkable tenement close in the West End of Glasgow. For the residents of 185 West Princes Street, the shabby object’s sudden disappearance might have seemed inconsequential. To the young man who took it, fleeing down the street with his prize clutched under one arm, it meant everything.

His name was Gary Watson, and that doormat was a souvenir – a piece of history, in his eyes at least. Almost four decades earlier, two young men of the same age were making history in that building. From a shabby bedsit on the second floor, they were about to change the way Glasgow defined itself, challenging every stereotype about Britain’s heavily industrialised Second City.

Today, their legacy is still felt here. More than that, it’s shaping the way millennials and young creatives view Glasgow, and their place in it. Scotland’s largest city has always struggled with a reputation for hard men and dangerous streets. Today a thriving music scene and an ever-expanding network of young entrepreneurial artists are changing the way people think about Glasgow.

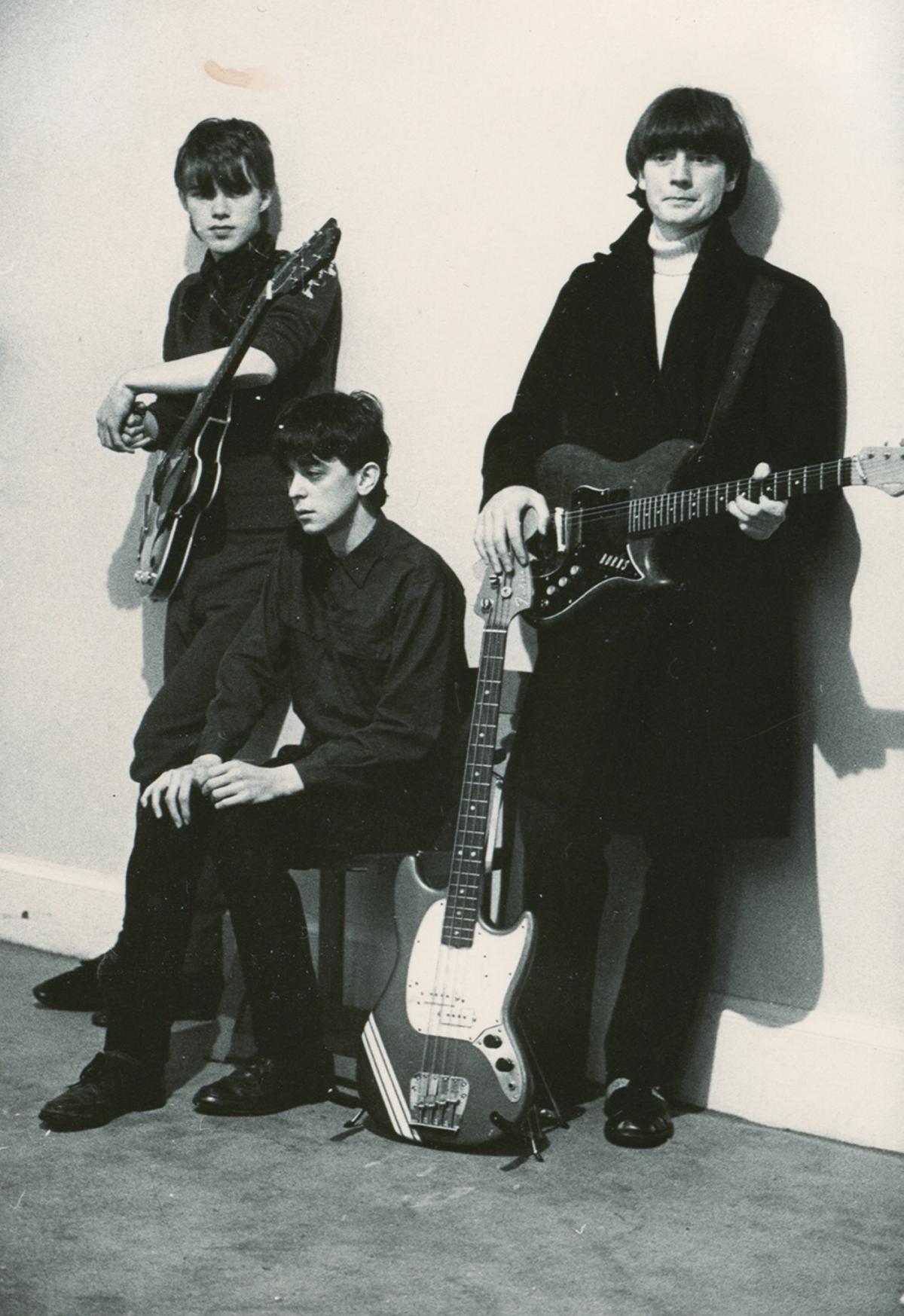

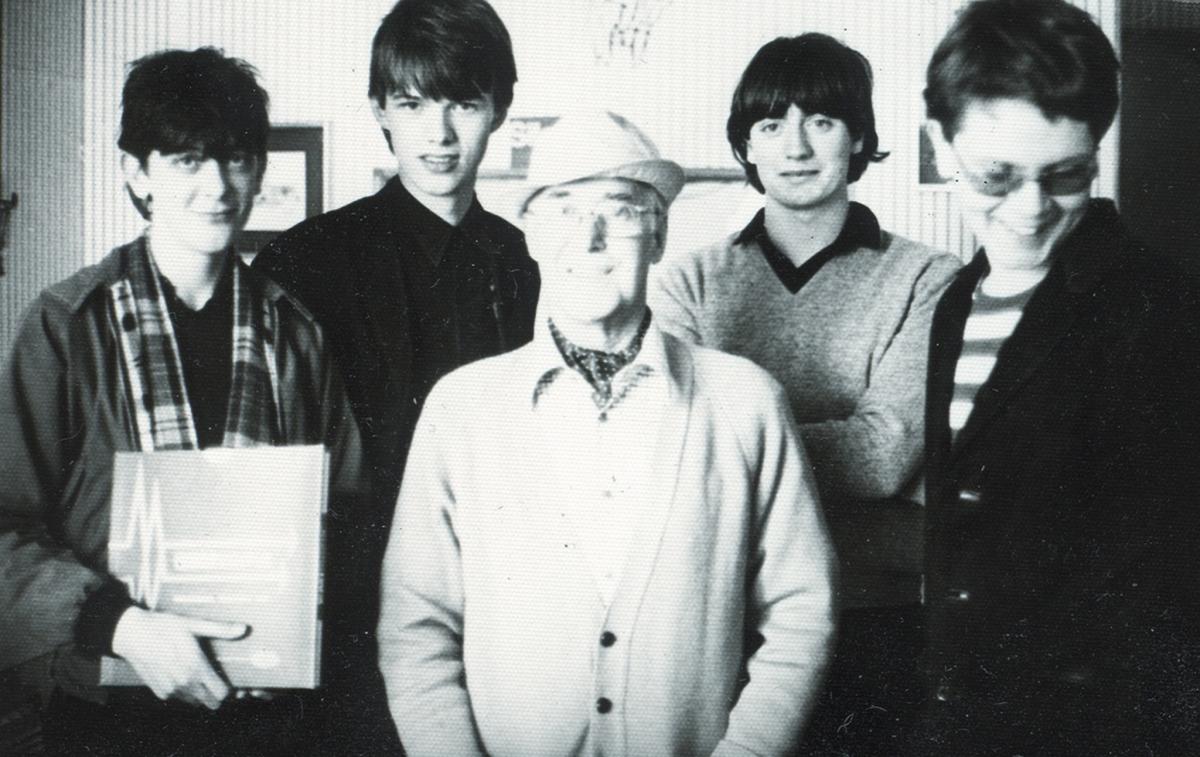

The seeds of change were sown in the late 1970s, when two teenagers began a short-lived but enormously influential partnership. Their names were Edwyn Collins and Alan Horne. Collins formed the band Orange Juice in 1979. More importantly, he and Horne founded a record label to promote the group’s music. The company, such as it was, became Postcard Records, operating out of Horne’s cramped bedsit.

Postcard Records would last for only two years, but they signed a raft of exciting new bands and caught the attention of the major labels in London. Ironically, their success was their downfall, as the groups they worked with – including Orange Juice – would eventually move south, after being picked up by English talent scouts.

Yet the ethos that defined Postcard Records did not die with the company’s closure in 1981. Alan Horne believed that Glasgow bands didn’t need to rely on the major players in London to find success.

They could do it themselves – anyone could.

More than 30 years later, a young man with the same conviction sprinted along West Princes Street with his trophy under one arm.

“I’m sure that doormat wasn’t around in the 80s,” says Hannah Vanessa Thompson, a close friend of Watson. She fronts The Van T’s, a Glasgow band that has leapt to the forefront of the local scene. “I told him, ‘You just stole someone’s bloody doormat!’ but it didn’t matter.

“‘I don’t care,’ he said, ‘I’ve got a piece of Postcard Records.’”

Gigs and shows will accompany Rip It Up exhibition at National Museum

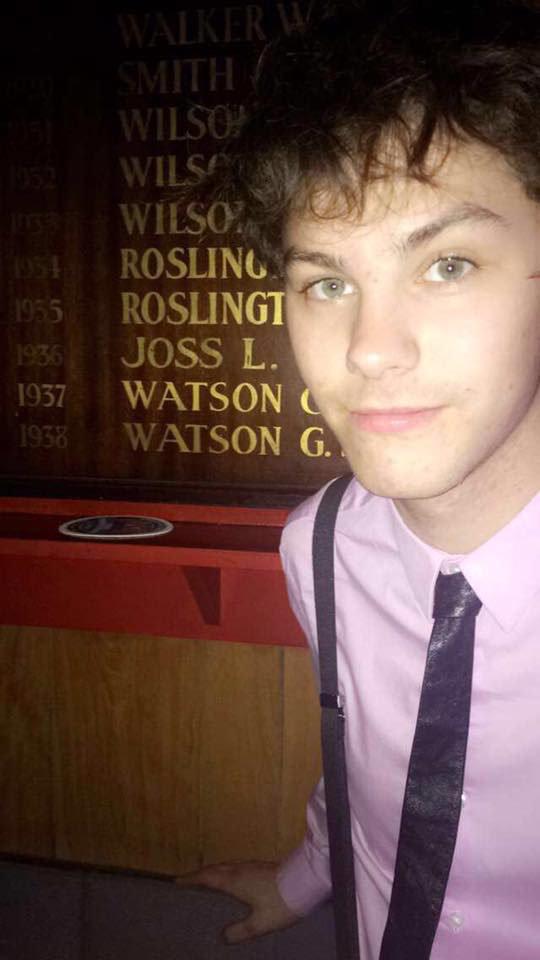

For Thompson, like many of the young creatives now defining the music and arts scene in the city, Postcard Records has a deep personal significance. Watson, whose band The Lapelles was set for success on the national level in 2016, introduced her to the label’s remarkable story when they met at a gig.

“Gary had all these ideas and passions,” explains Thompson. “He was like Alan Horne. They were both people who wanted to make something that was their own, that was different. Something unique.”

The Lapelles were certainly on the rise, but they weren’t the only ones. A number of new and ambitious musicians have appeared in recent years, forming a close-knit community of artists and fans. From the danceable alt-rock of The Van T’s to The Vegan Leather’s 80s-inspired synthpop, there’s no shortage of exciting “ones-to-watch” in the city.

What do all of these groups have in common? They’re just some of the many acts that cite Orange Juice and Postcard Records as a major influence, specifically on their attitude to promotion, attitude, and ethos.

“Gary brought that DIY attitude to The Lapelles,” says Gianluca Bernacchi. His band, The Vegan Leather, is currently recognised as one of the scene’s most prominent groups. “In turn, that Postcard attitude started to rub off on the rest of us.”

There are more than a few similarities between The Van T’s and The Vegan Leather. They both played explosive sets at last year’s TRNSMT Festival at Glasgow Green. Separately, they each became close friends of Gary Watson and The Lapelles. Underpinning it all is a shared love for Postcard Records.

“Sound-wise, a lot of the bands are doing their own thing,” Bernacchi adds, “but everyone in our scene’s going DIY. They’re going to smaller studios in Glasgow, or recording themselves in their homes, and having creative control over it all. The mentality that Postcard Records followed is something that lives very strongly in Glasgow, and in the current music scene in particular.”

That mentality was largely crafted by Alan Horne, whose flat on West Princes Street became the Postcard Records headquarters. From the wardrobe where he kept his paperwork to the pseudonym under which he ran his accounts, he was determined to succeed without help from the mainstream labels in London.

Horne is an enigmatic character to this day. While Collins went on to gain global fame with his solo hit A Girl Like You, Horne was a much more private individual. In fact, much of what he know about him – the character that Watson, Thompson, and many others now view as an inspiration – comes from a single source.

Gigs and shows will accompany Rip It Up exhibition at National Museum

Simply Thrilled: The Preposterous Story of Postcard Records was a 2014 book written by Simon Goddard, a music journalist with a passion for the subject.

Watson often carried a well-read copy of the book with him, and in the last two years it has served an essential role in forming the image of Postcard Records that many Glaswegian millennials are now so enamoured with.

“I wrote the book for love rather than money,” explains Goddard, “which in itself is the story of Postcard in a nutshell. It was always going to be, at its heart, the story of Alan and Edwyn. There were other key people in Postcard … but ultimately it’s the story of Alan and Edwyn. Their story is the story of Postcard.”

That story served as the inspiration for a key element of Watson’s vision, in what has since become a focal point for the city’s creative community.

In 2016 he launched The Spaghetti Factory, named after a West End bar that Collins and Horne frequented. The project involved a series of sessions and interviews, filmed by young cinamatographers and acting as an intersection for multiple different artists and creators.

“In terms of roles, it was just ‘do what you can’,” says Michaela McEnjoy, one of the main producers behind the series. “Gary had a great idea, so we just tried to make it happen.”

The project has seen filmmakers, artists, musicians, and event organisers pooling their resources to build a genuinely independent creative outlet. Furthermore, the majority of the first season was funded by fans and members of the local scene. Mathew Johnston, another producer, coordinated the process of raising the money.

“Gary wanted to make something to mirror Postcard,” he says. “Something quirky and different. The bands that are on the scene at the moment are all helping to create Gary’s vision.”

It’s a vision that, tragically, Watson himself was unable to realise. With The Lapelles poised on the edge of their big break, in discussions with a major label and with a rapidly expanding fanbase, it all came to an abrupt end. The young singer was involved in a sudden accident, and passed away in August 2016.

Echoing Postcard Records, his legacy lives on. With only one third of The Spaghetti Factory’s first season filmed at the time of his death, the community rallied together to finish the job, with everyone – from the local scaffolder who built their stage to the camera crews documenting the project – working to make Watson’s dream a reality.

The importance of committing The Spaghetti Factory to film can’t be understated. The events have allowed a range of filmmakers and cinematographers to collaborate. Within Glasgow’s independent film scene, the Postcard ethos is now an animating force.

Kieran Howe, one of the main filmmakers who worked on The Spaghetti Factory, recently founded his own production company – Odd Socks Films – while in the last two years a string of short features and documentaries have been released under the moniker of Postcard Pictures.

As the name suggests, this latter collective draws inspiration directly from the same source as The Spagehtti Factory. At its centre is Antonis Kassiotis, a young writer and director.

“Even though I’m not in music myself, it was important to find that philosophy and apply it to my own craft,” says Kassiotis. “I make movies, but the independent spirit with which Postcard Records was run is very exciting.”

The work of Postcard Pictures ranges in style and genre. Following on from several award-winning documentaries, Kassiotis produced his short film The Big Spread, which has already gained attention in Glasgow and around the world.

“Postcard had an unapologetic attitude to making music, and making anything,” he says. “You shove it in the world’s face and you make them like it. That’s what you’ve got now – you look around the city and you’re surrounded by people with the same dream. You’re part of a bubbling community of artists.

“Postcard, ultimately, is about young people doing great things – young people punching above their weight.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Goddard, quite literally the man who wrote the book on Postcard Records. When asked to define the ethos of the label, he paints the same striking picture.

Gigs and shows will accompany Rip It Up exhibition at National Museum

“The triumph of romance over resources,” he says. “Dreaming big with the little you have. Having a go. Not being afraid to fail so long as you enjoy it. It’s about having that belief, that romance in your art whoever and wherever you are. Postcard is about that idea as much as any music.”

It’s a simple idea, really. You can do it yourself – anyone can.

@WritingHiggins

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here