SYDNEY Devine arrives in the Glasgow café looking far from his normal ebullient self, ostensibly to talk about his upcoming Scottish tour. But given the events of recent weeks, in which the rhinestone cowboy from Cleland in Lanarkshire lost his son Gary to sepsis, it’s a surprise he’s here at all.

Devine is enduring a tragedy greater than the lyrics of any country and western song he’s ever sung. And its impact is lined into his 78-year-old face. The entertainer’s car sales manager son was just 57 when he died a month ago after contracting sepsis, and had little warning of ill health.

You sense Devine wanted to meet up today not to sell tickets or to reveal why he couldn’t cancel the tour, but simply to connect.

“Yes, on tour again, at my age, but on the back of what’s happened I really think it’s a good thing,” he says in soft voice as he places his cappuccino on the table. “You can imagine what’s been going through my head.”

To be honest, I can’t imagine, Sydney. I can’t imagine what it’s like for a parent to lose a child. It shouldn’t happen that way. I can’t imagine what it’s like to turn up at the hospital, thinking your son has had food poisoning only to be told he has little hope of recovery.

“No, you’re right. And I appreciate you saying that because all too often people like to suggest empathy. I’ve done that too. But the truth is this is a level of grief that can’t be shared with anyone. And you can’t know what it’s like. When my mother and father died I was heartbroken, but this is an entirely different type of pain.”

He swallows hard, the words difficult to form. “I don’t have any enemies in this world, but if I did I would never wish this on anybody. I can’t comprehend it.”

Devine works hard to hold it together. He hasn’t taken his first sip of coffee yet. “When you watch your son die in front of you it’s the worst thing. And I will never get over it. I think about him all the time, day and night. I try to block it out of my head with other thoughts but it’s just not possible. When I go to bed at night I try and think of other things. But my thoughts always go back to Gary.” He pauses and adds, “Maybe, at some point in the future . . . but not now. Certainly not now.”

The singer reaches for the coffee cup. You hope the caffeine hit will help him a little. It’s as much as you can hope for. Over the years, I've always been a good relationship with Devine. A nice man in a very tough business. He has always been decent, always self-deprecating, yet a great believer in his ability to entertain.

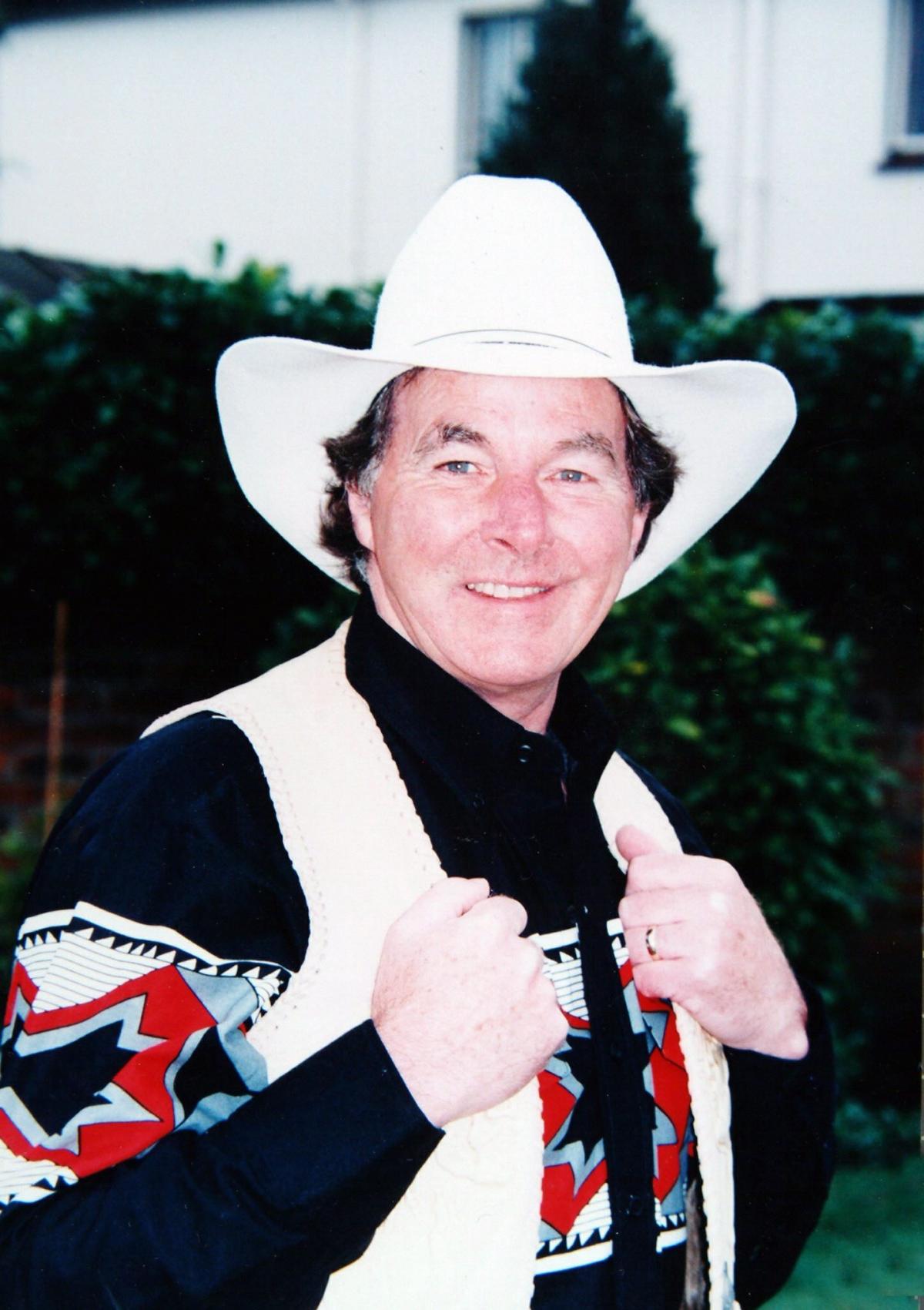

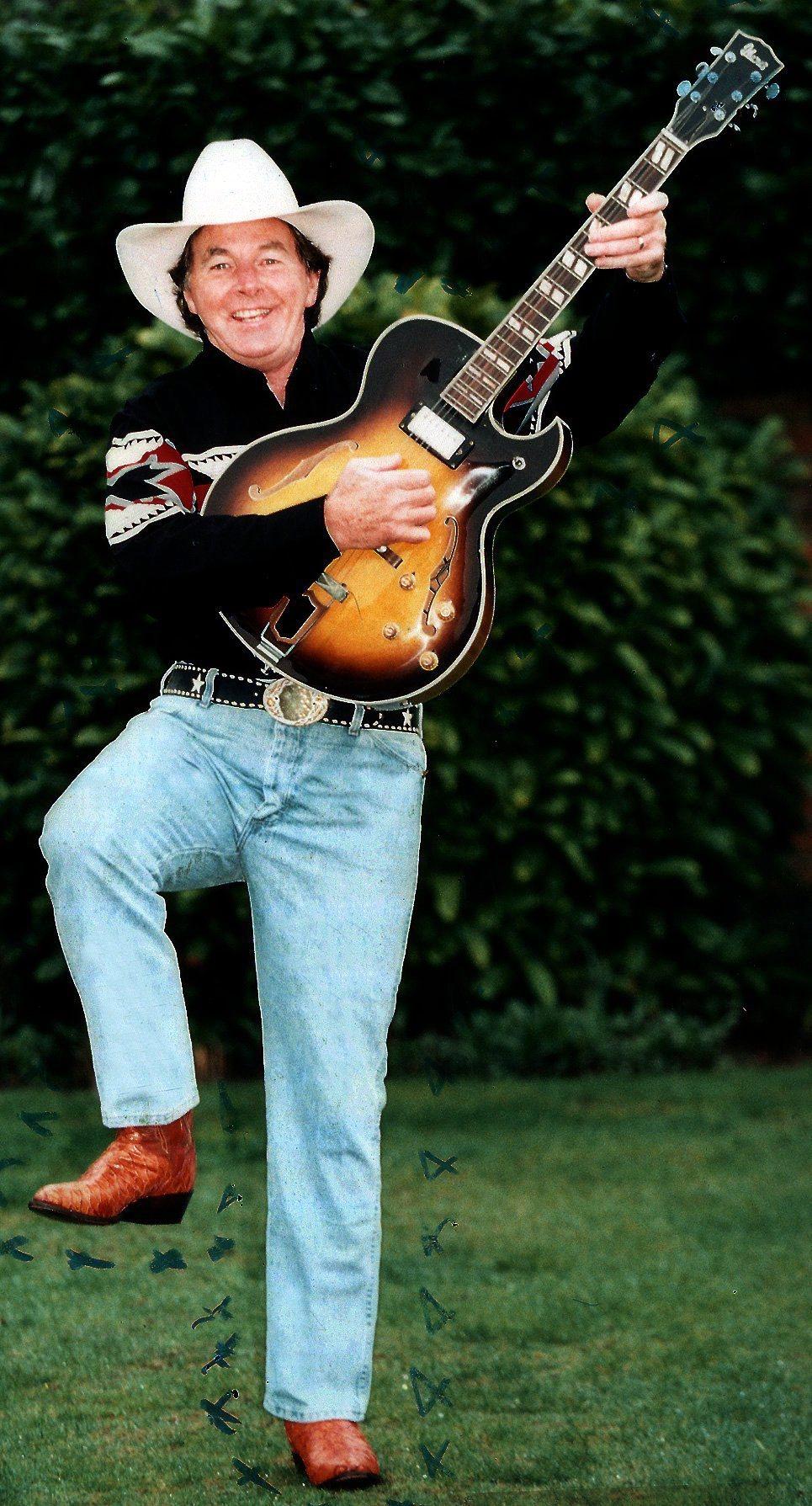

Since beginning his career as a 13-year-old boy whistler on the variety circuit, he’s gone on to sell almost 45million records such as Tiny Bubbles, Maggie and Crystal Chandelier and has had a career as long as Willie Nelson’s hair. It’s partly down to hard work. But success has also been predicated on retaining his Scottishness, mixing it in with Americana to produce a hybrid fans adore. He certainly deserves respect for surviving and thriving in a business that eats up performers like Texans eat Pecan pie. Right now, Devine is nibbling at the edges of a lemon muffin but you sense what he’s really hungry for is a hug.

“I suppose through time the pain will ease,” he says. “But I never realised it would be this hard.”

Thinking of the great moments he had with his son helps a little. “I think of the devilment he caused,” says the singer, breaking into a smile. “Gary loved life. You know, I thought I grabbed all life had to offer but I was at the back of the bus compared to him. Yet, I wish he were doing that right now. I realise he’s gone. And that’s the overwhelming feeling which races into my head. And that’s hard to deal with.” His voice becomes brittle. “Today, I’m in Glasgow to tie up affairs of his estate. It’s still happening . . .”

Father-of-three Devine, who lives in Ayr just yards from the beach, is sharing his grief with wife Shirley whom he met while performing in Aberdeen in 1958. “Sometimes tragedy can pull people apart, but we’re very close. We always have been.”

The current tour had been organised six months ago. With the death of his son, many expected Devine to cancel? “I couldn’t legislate for what had happened. And afterwards, I did wonder if I could go out there.” He takes a gulp of coffee. “Before each tour I like to prepare. I like to be fit. I practise the vocal chords, I sing quite a bit. But how could I feel like singing with all this going on?”

Devine was all too aware it’s the performer’s task to make people happy, to bring smiles to weary faces, to uplift lives away from the dull ache of routine. Yet, he is the man aching inside, every fibre of his being missing his son. “And when you add to that I’m singing country songs, where usually 14 people are killed in the first verse,” he says with a wry smile. “But on this occasion I shall pick my programme very carefully.”

Sydney Devine, MBE is also very much aware his relationship with the audience is a two-way process. He entertains them – and they in turn adore him. He can appear before 1600 people and they sing his praises. That must help? “Yes, it makes me think how lucky I am. But you have to give before you take. I’ve always been a giver. Money has never been of any interest to me whatsoever. Yes, I live in a nice house, but I don’t need much at all. Today, I came into Glasgow on the bus, using my bus pass. I haven’t forgotten where I’ve come from. And I work hard on stage.”

He does. He gyrates. He swings his hips. He sweats. He hollers. Most importantly, he connects. “There are four generations come to the shows,” he says. “And sometimes I wonder why. I guess it’s like those who go to see pantos more than once. It’s a familiarity. But I do know I’ve never forgotten who pays my wages, those who have let me feed my children, live in a nice house and buy a nice car.”

The conversation lightens when we reflect on Devine’s career path. He smiles as he rewinds into the mind of the young man who first stepped on stage. Can he remember why he wanted to become a performer? “Because I was too nervous to steal,” he says, smiling. “And I didn’t fancy becoming a coal miner. Why would I when there was coal in the bunker? I saw no need to go down there.”

Over the years, Devine has had his share of hard knocks along the way, the business deals that collapsed. “I once gave an agent £78,000 for nothing, to get out of a dodgy court case. But I dusted myself down and got on with it. And yes, I’ve ended up with a Mercedes and a nice life but when envious people point this out I say ‘Yes, but that represents a lot of songs.’” How many times has he sang Tiny Bubbles over the years? “Not enough,” he says laughing for the first time.

What’s evident is Sydney Devine is far from consumed with bitterness. Indeed, he has always leaned towards belief in a greater being. But has the loss of his son rocked his faith at all? “It’s a good question but I think you pray when you’re in trouble, where there’s a crisis,” he says. “I think it’s great to believe. And it can help. And I’m not bitter. It’s life. And death. You can’t legislate for any of it.”

He adds, “In many ways I’ve been very lucky in life. I’ve survived aneurisms and heart attacks. And I’m still here. Although I would gladly swap places with my son if it meant I could bring him back.”

We switch track. Back to happier times. We talk of a recent Johnny Cash documentary which leads into his own appearances in Nashville. He smiles as he recalls it. “I was recording with top musicians, and smoking at the time. During a break, one of the session musicians asked if he could share my cigarette, with a look of wide-eyed expectation. He reckoned it was dope. In actual fact it was a Player’s Plain. He took a drag on it and looked like he felt stoned.”

He loved recording his Nashville albums. “It was a phenomenal time. But it was the worse-selling album I ever made.” Too American, not Scottish enough? “Perhaps. Yes, I think fans liked the fact I didn’t lose my roots.”

Devine’s voice takes on a strength and he returns to his loss. It’s not surprising conversation roads lead back to his son. Sydney Devine can’t not speak of him. “If there’s anything good has come out of this, and there isn’t a lot, it’s that awareness is all important. And there’s an understanding of how ineffective antibiotics can be these days. Every drug known to man was pumped into Gary, every tube inserted. He was even tried out on dialysis. But from the time he entered I think they knew he was in trouble.” The singer adds, “Gary was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes two years ago. Doctors, I’ve learned, believe this can make people more susceptible to sepsis.

“What has helped is friends,” he offers. “A pal from West Sound Radio [where Devine once worked] sent me a card and on it was written ‘Grief is the price you pay for love.’ And that’s so true.”

He takes a final sip of coffee. He seems a little more composed. “I’m glad I met with you today. You’ve made me laugh. I feel better.”

Ready to perform again? “Ready,” he says. “I need it. I really do.”

Sydney Devine will be appearing at Largs, Barrfield Theatre April 13, Motherwell Civic Centre April 20, Falkirk Town Hall April 29 and

April 13, April 20, Dundee Whitehall Theatre April 22, Falkirk Town Hall, April 29, The Gaiety Theatre Ayr, April 28. He will appear at the Pavilion Theatre Glasgow, November 9-10.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel