IT BEGAN last week when Walker and Bromwich’s Dragon Of Profit and Private Ownership was let loose on the Royal Mile. A crowd had gathered in Trinity Apse, the church that once was the Brass Rubbing Centre just off Edinburgh’s main historic drag, to watch its escape, although some children, faced with the size of the green rubbery beast, were wondering how on earth they were going to get it out the small front door. “Perhaps it will fly,” said one very tiny one. No such luck, although it did need four volunteers to deflate it, a sort of slow motion wrestling match which seemed almost as relevant as the performance itself. It certainly got a few laughs.

Walker and Bromwich, who have performed similar socially-minded parades (most recently with a giant pink inflatable love canon) on other occasions, were inspired in this by the philanthropic social idealism of Sir Patrick Geddes, the loose basis for much of the commissioning programme this year, and a Northumberland mine workers banner which used the dragon as a symbol in a bid for social reform.

The dragon reinflated and various bystanders co-opted as Geddesian “leaves” – “By leaves we live, not by the jingling of coins,” they cried out at various points – the lot marched up the Royal Mile to the sound of a brass band, before a performance in which the working man eventually “killed” the dragon. Who knows what the tourists thought, but its mummers scored their points with very good humour, with Tam Dean Burn as the working class hero.

More outdoors art at Jupiter Artland, where Pablo Bronstein unveiled his somewhat outlandish Rose Walk. Bronstein’s practice ranges from drawing to choreography, always inspired by architecture, often satirical. He creates illusory worlds on paper which appear real, melding the modern and the historic. The Rose Walk is like one of his pencil sketches come to life, an imagined history made real. A curious double ended structure of two oversized white pavilions, one Gothic in style, the other a detailed Chinoiserie, they face each other, somewhat improbably, across a narrow, enclosed pathway flanked by what will be red and white roses, as if in overblown celebration of this tiny thoroughfare. A nonsensical folly, the scale is skewed, the proportions out. It’s all slightly Alice in Wonderland, although no pots of paint and brushes have been left to re-tint the buds. It was the stage for a short performance in which two dancers mirrored, in part, each other’s movements, the dancer at the Gothic end curlicued and elaborate, the dancer facing her more circumspect. There’s an opposition of styles and cultures, of attempts to traverse linguistic or cultural barriers, but also the nagging feeling that something is lost in translation.

Marco Giordano’s temporary summer installation is a series of sculptures that, Gardens of Tivoli-like, emit what might be called a scotch mist over those who walk past, just in case you’re not already feeling damp and cool enough this summer. The Glasgow-based artist calls them “blessings” and there’s something unsettlingly ritualistic as well as witty about them, surreal totems emerging from the undergrowth, as if history is breathing down its (gold-plated, in this case) nose on us.

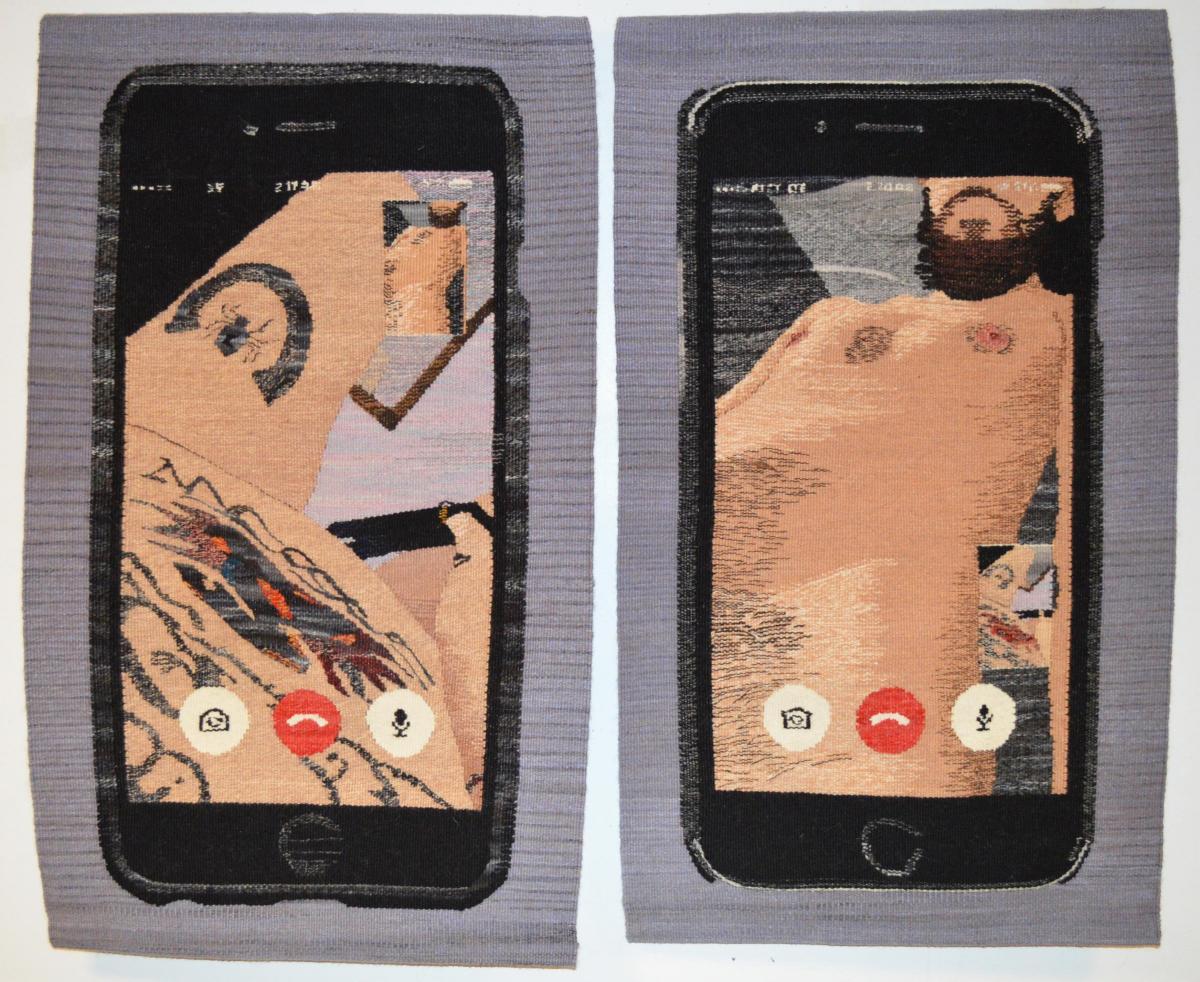

There are more offerings on the walls at Dovecot with “Daughters of Penelope”, an exhibition of tapestry and woven arts created by women weavers and artists at Dovecot. Dovecot’s history has been charted in recent exhibitions. Its founding years were exclusively male, but with the advent of Maureen Hodge in the early 1960s, the much-admired weaver who collaborated frequently with Elizabeth Blackadder, the balance began to change, until Dovecot had its own female directors. There is a fabulous array of tapestry and weaving here, from Christine Borland’s lovely and thoughtful work partially undoing the weaving of Malawian Hezileki Perekamoyo to Joane Soroka’s equally thoughtful and rather moving Sendler tapestry, which works in 2,500 gold-painted ash keys to mark every child that Irena Sendler saved from the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto. The soundtrack to it all is Hanna Tuulikki’s cyclical, haunting duet with a Lewisian singer, a drawn-out reworking of a Gaelic Isle of Lewis weaving song echoing that nature of spinning itself.

A half hour’s walk down the paths that are the former train routes of north Edinburgh takes you to the Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop at Newhaven, conveniently right on the cycle path . Charlotte Barker’s fabulous, large vessels in black and white teeter on carved wooden benches which themselves sometimes seem to defy gravity in their elongated three legged form. There is a wonderful purity of form here, weighty yet light, the hand marks of building visible in the surface under the matt glaze, picked up by the grey late afternoon light coming through the windows. The variety of form is distinct yet subtle, from moon jars to rectangular vessels and jagged forms. On the walls, leaf imprints in black, the whole a series of pot-landscapes with very pleasing depth. Well worth a trip out from the town centre galleries.

Edinburgh Art Festival, various venues until August 27

edinburghartfestival.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here