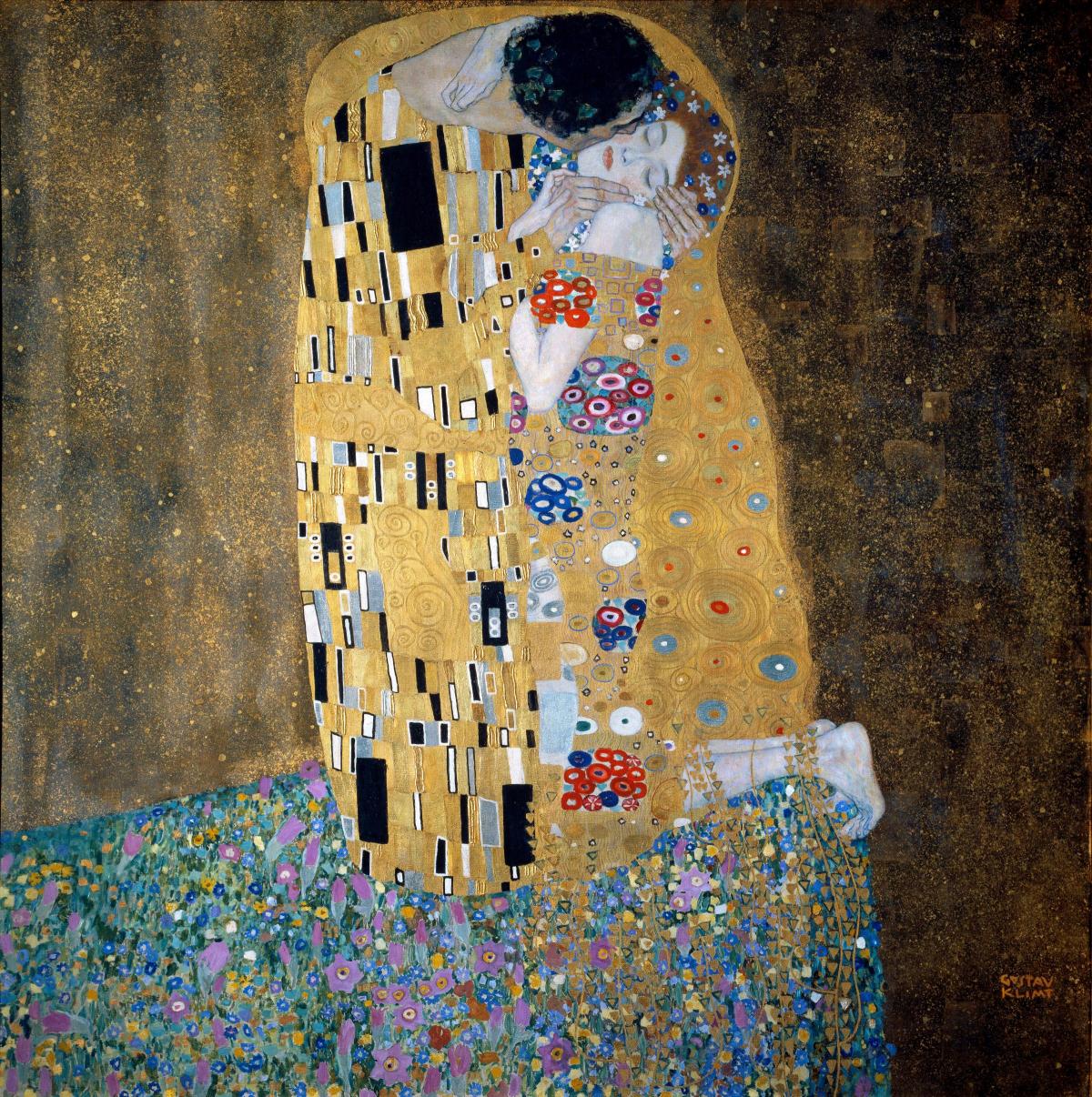

IT is one of the most famous images in Western Art, a beautiful depiction of two lovers wrapped in an intense and elaborate embrace.

Gustave Klimt’s Art Nouveau masterpiece The Kiss still has the ability to captivate and disturb viewers today, just as it did in Vienna in 1908 when it was first exhibited and caused such a sensation. But it may not have been painted at all had it not been for the influence of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his creative circle, argues one expert.

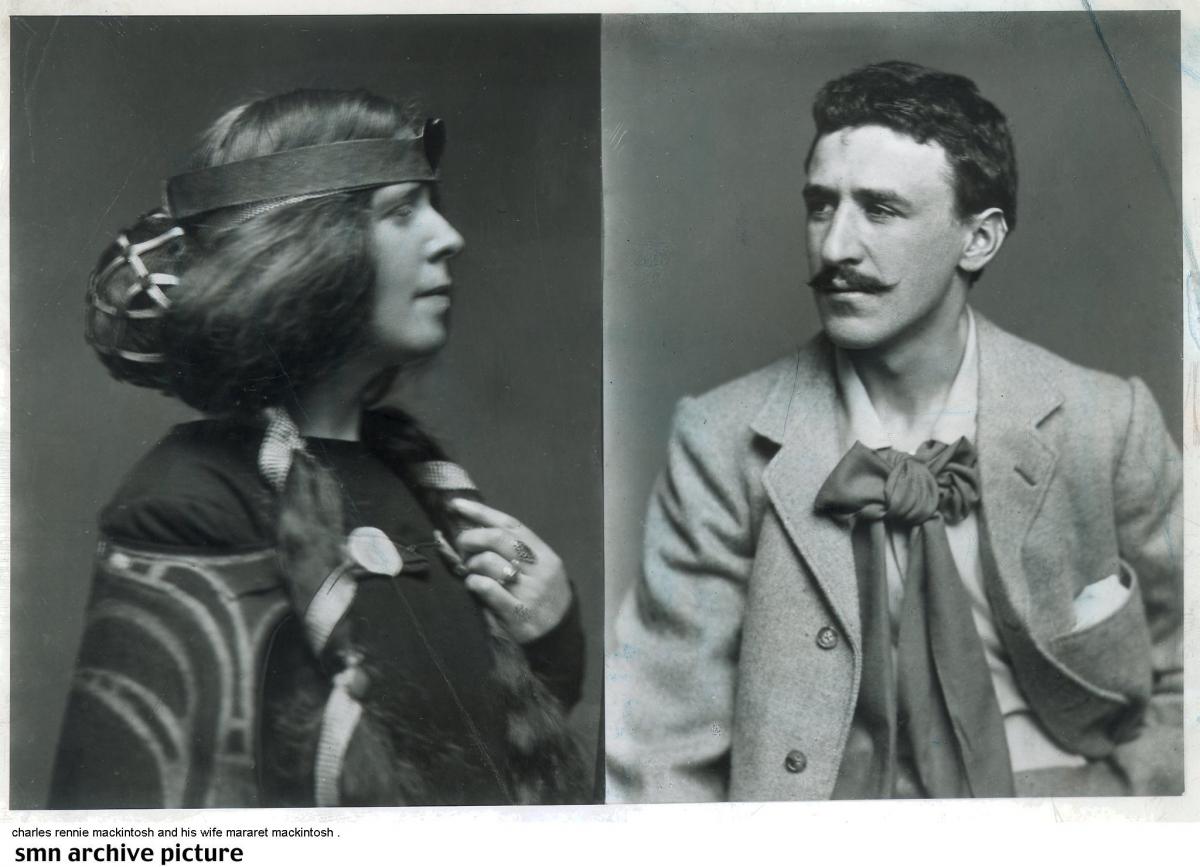

The modern style being created in architecture and design by Mackintosh and his close associates in Glasgow in the late 1890s and early 1900s was being feted across Europe at a time when few in the UK recognised its significance. And, following positive reviews in German and Austrian art magazines, Mackintosh, his designer wife Margaret Macdonald, her sister Frances Macdonald and her husband Herbert McNair, were invited to show at the eighth Vienna Secession exhibition in 1900.

The Four, as were known, made an immediate impact. Like Mackintosh and his circle, the Vienna Secessionists were also looking to break from the past and find new ways to create and interpret art and design, and they found kindred spirits in Glasgow.

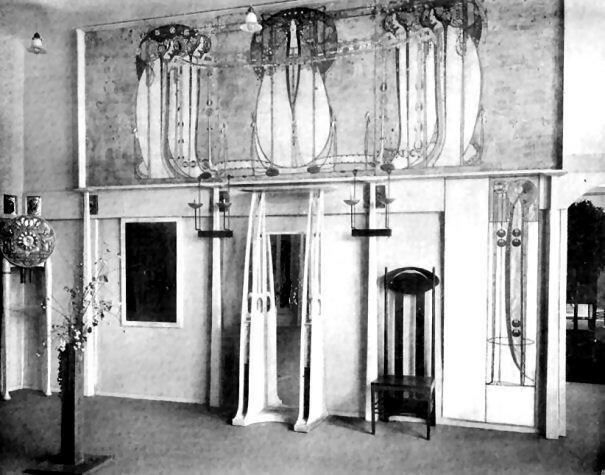

A surviving photograph of Mackintosh’s room at the exhibition highlights just how radical his ideas about interior design were. Gone is the gaudy Victorian fashion for crowding furniture, replaced by an elegant minimalism that would have seemed both shocking and exciting to contemporary eyes.

Sparse pieces of furniture - including one of Mackintosh’s iconic high-backed chairs – are set against tastefully decorated walls. Placed high on one of them is Margaret Macdonald’s stunning gesso panel The May Queen, a wide, three-section piece depicting stylised female figures that was originally commissioned for Miss Cranston’s Ingram Street Tea Room in Glasgow. Macdonald’s work currently has pride of place at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum as part of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Making the Glasgow Style exhibition, staged to coincide with the 150th anniversary of his birth.

The room in Vienna was both a critical and commercial success, and artists and designers such as Klimt, architect Josef Hoffman and Koloman Loser were impressed and inspired.

“The work of The Four was a revelation to the Viennese, with Klimt and Hoffman particularly taken aback,” says Stuart Robertson, director of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society. “In fact, Klimt’s career was on a bit of a decline at the time and he was particularly inspired by what he saw. You can see the influence on his later work – there is a point where he changes his approach.

“I don’t think you would have seen work like The Kiss if it hadn’t been for Mackintosh and the Glasgow influence.

“We see this influence directly in the Beethoven frieze Klimt did in Vienna in 1901.”

Indeed, the Secessionist exhibitions that followed the visit of The Four immediately picked up and ran with elements of the new Glasgow style, moving towards stripped back, de-cluttered interiors a la Mackintosh and Macdonald, an approach the couple were fully embracing at their own flat in Mains Street, Glasgow, now the corner of Blythswood Square and Bath Street.

According to gallery owner and writer Roger Billcliffe, what appealed to many Europeans was the way the Glaswegians treated each room as an entire work of art, a concept referred to in German as Gesamtkunstwerk.

“This concept already existed in the Germanic way of thinking, but Mackintosh was reinventing it and giving it new use and meaning in the modern world. His designs made a real impact and liberated what furniture could look like.

“Mackintosh was interesting because he ignored how people usually made furniture at the time - he designed a shape and told the craftsmen to build it. He wasn’t defined by the limitations of the material.”

The artistic reputation of Mackintosh and The Four was gaining traction on the continent and in 1902 they were asked to exhibit at a major exhibition of contemporary decorative arts in Turin, Italy. Each had their own room and followed similar principles to the Vienna exhibition, showcasing composed walls with only occasional pieces of furniture.

In the years that followed, the Vienna Secessionist artists, designers and architects flourished too, buoyed by commissions from rich European patrons. One of them, the textile industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer, also revered Mackintosh, and travelled to Glasgow to meet him and Macdonald. He hired the pair to work on his house in Vienna.

And, when the Secessionists were setting up their ground-breaking studio and workshop in Vienna, the Wiener Werkstatte, it was Mackintosh they turned to for advice. By this time World War One had broken out, however, and he was unable to make the journey from Scotland to Austria. He sent them a letter saying: “I wish I could be with you, I would help you with a mighty shovel.”

“They shared a relationship based on inspiration,” explains Robertson. “Hoffman saw Mackintosh as the leader of the modern movement, a spiritual brother. And Mackintosh was hugely supportive of them in return.

“Indeed, it is my own theory that if war had not broken out Mackintosh and Margaret may well have gone to live in Vienna – that is where his accolades were coming from. Many in Germany also admired his work and there were more wealthy patrons willing to spend money there and in Austria. By this time Mackintosh had also exhibited in Moscow.”

But where the likes of Hoffman and Klimt were being hired for dozens of commissions a year, Mackintosh received only two or three in Britain. This, according to Billcliffe, set the Glaswegian back in comparison to his European peers.

“Mackintosh simply didn’t get the same type of exposure here as he did in Europe,” he says. “In Scotland he didn’t really get a fair crack at the whip because apart from the likes of Kate Cranston and William Blackie [for whom he designed The Hill House in Helensburgh], there weren’t many clients around looking for cutting edge architecture.

“Most wealthy people want to be a bit flashy. They want to say “look what I can afford”. You don’t really get that with Mackintosh.”

Indeed, in 1915 Mackintosh and Macdonald moved to Suffolk, then later to Port-Vendres in southern France, where he mainly concentrated on watercolours. The couple returned to London in 1927, but a year later Mackintosh died of cancer of the throat and tongue.

In central Europe Mackintosh remained influential, particularly as the likes of Hoffman went on inspire influential modern pioneers such as the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier.

“In Germany Mackintosh still has a significant reputation,” says Billcliffe. “Had he lived longer, however, I don’t think he would have followed the Bauhaus style. Those designers were trying to break with the past, where Mackintosh was trying to bridge the gap between the past and the present.

“Indeed, many Europeans still come to Glasgow specifically to see the work of Mackintosh, and while they are here they discover other Scottish artists and architects. He remains an influence in himself and a gateway to the work of others.”

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Making The Glasgow Style is on now until 14 August at Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery. Tickets are £7 and £5, children go free.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here