Stephen Boyle

In the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment, psychologists gave children a choice between a marshmallow now or two marshmallows in 15 minutes. Children who waited tended to do better at school and in later life. Scotland needs to pass its own marshmallow test if we are to capitalise on the opportunity to improve our economic performance. Doing so in 2016 will be challenging as we deal with a declining oil industry and a world economy in which growth is slow or slowing in important markets.

One of the brightest spots in the world economy is the UK. It will grow for a seventh consecutive year, albeit at a slower pace than in 2015. Consumption and business investment will lead the way. Trade again looks set to disappoint, hobbled by a strong pound and weak demand in Europe. Fiscal repair means a modest contribution from government. Growth will be sufficient to boost employment, pushing unemployment below five per cent.

Despite consistent growth and low unemployment, inflation remains a distant threat. Even as the effects of the oil price fall and sterling’s rise begin to fade, price pressures will remain modest. A consequence of the depth of the last recession and a series of trade union reforms is that labour lacks the confidence and the strength to push for large pay rises. With inflation bottled, Bank Rate will likely remain at 0.5 per cent throughout the year.

The main threats to UK growth come from abroad. The euro zone continues to struggle with high unemployment and slow growth. The Five Presidents’ commitment to devote the next ten years to completing fiscal and political union along with the euro zone’s adherence to intrinsically growth-limiting monetary and fiscal policies mean slow progress there for years to come. That matters to the UK, as Europe remains by a distance its largest export market. The downside risk comes from more banking or sovereign debt crises, which would seriously dent UK growth.

China’s slowdown is a product of excessive investment funded by borrowing mainly from its banks. A financial crisis is avoidable as the state has the resources to recapitalise banks. Slower growth still, seems likely, however. While China is of modest direct importance to the UK, the effects on countries like Germany that make substantial imports to China will affect already-weak Europe and, hence, Britain. The worse outcome would be a full-blown crisis, leading to a very sharp growth slowdown.

For Scotland, the picture is more troubled than in the UK as a whole. A gap has opened up between unemployment here and in the rest of the UK. Data published last week showed Scotland barely growing between July and September last year. The monthly Purchasing Managers Index surveys show Scotland flirting with recession while the UK motors along at a decent enough rate.

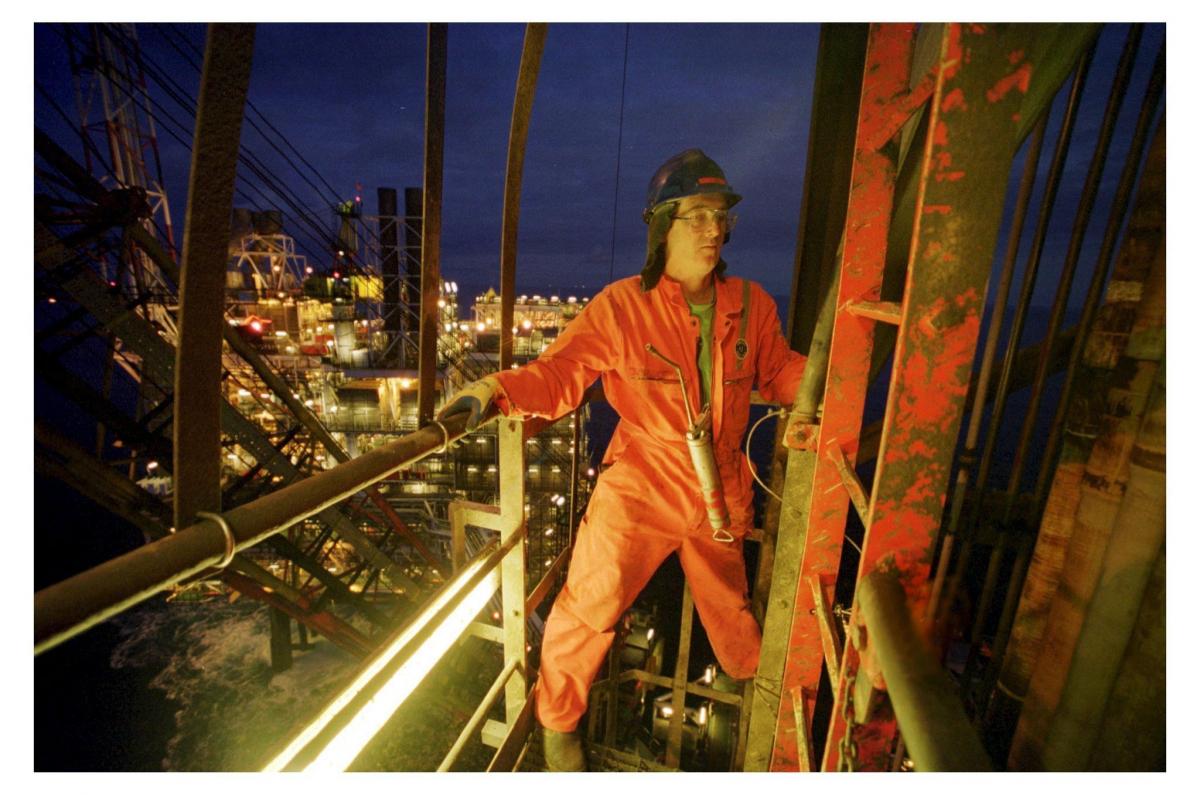

The reason is oil and the impact is most evident in the North East. There are 406 council areas in the UK. Of these, five saw a rise in the number of people claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance, a measure of unemployment, in the last year. In three of these, the rise was no more than three per cent. In the other two, Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire, the increase was almost 60 per cent. Rents, house prices and hotel occupancy and room rates are all falling in the city and its hinterland. To date, the oil supply chain has weathered the storm by cutting costs and drawing on its cash reserves to mitigate the fall in demand that followed the 65 per cent price fall of the last 18 months. With the need to cut costs by 40 per cent from 2014 levels to make new investment profitable at $60 per barrel, never mind what $30 would require, more extensive restructuring of the industry will take place in 2016. Its effects will spill into the wider Scottish economy, slowing growth.

Challenges like this make passing the marshmallow test all the more important for Scotland. We are already a rich and successful nation, close to the top of any global league table. Yet income per person here lags 30 per cent behind the best performers. We could be £10,000 per person per year better off if we were more productive. As well as more money in people’s pockets that would mean the opportunity for more generously funded public services.

There is no secret formula for faster economic growth. All it takes is investment that creates new and better assets than those we have today. Superior assets will generate more income tomorrow than we currently earn. But investing for tomorrow means sacrificing consumption today. We need to leave more of the marshmallows where they lie.

In choosing our investments we should follow the evidence about what works and then stick to our course for the long-term. When investing in people, by far the highest rate of return comes from investing in our very youngest. The earliest years are when non-cognitive skills like communication and perseverance develop most, or don’t. They are essential to effective learning, as well as to making people more productive workers when older. We have taken valuable steps towards this kind of support and education in recent years. Our scarce resources need to be skewed further towards our youngest children.

Scotland is currently benefitting from transport investment – for example, the Queensferry Crossing and the M8/M73/M74 – that has blunted the effects of the oil downturn. We know what types of transport investments yield the highest returns: roads that unblock congestion, allowing the network to flow more freely. The return on these is consistently higher than for most things on rails, including an allowance for the environmental impacts of different modes. Continued investment in such, often small, road projects will produce substantial benefits.

Ultimately, growth comes from technological progress, which in turn depends crucially on innovation. Research is an important cornerstone of innovation and we should persevere with an approach that concentrates investment in our very best universities. Yet the innovation that is most important in Scotland will be what each of us should do every day: learn from competitors, suppliers and colleagues about what they do and adapt it to our circumstances, thereby enhancing productivity. For that we need skilled people, which brings us back to the importance of human capital investment.

Investment is the right thing to do but it is not easy. Winning the prize of being £10,000 per year better off will not happen quickly. It will take at least the willpower and dedication of the child who leaves the marshmallow for 15 minutes.

Stephen Boyle is chief economist at Royal Bank of Scotland

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel