LAST week, Marks & Spencer announced that it is to close 100 stores by 2022. In a world of fast fashion and sophisticated budget supermarkets, the one-time favourite of the British middle classes is on the slide. But really what is remarkable about Marks & Spencer is that it has been so successful for so long, and said so much about who we are as a nation. One of its biggest-sellers, the prawn sandwich, tells us everything about what it has represented, and drawn us in with for so many decades. For, bundled up in those slices of bread, is a message of convenience, modernity and aspiration. It’s long been about those things that have made our lives easier, but also made us feel that little bit posher. The story of that sandwich, as well as many other technological innovations, is told in this, our guide to Marks & Spencer through the ages – what it’s brought us, what it’s meant to us, and how it’s changed us.

1880s

Pennies well spent

When Michael Marks first set up the penny bazaar that was the precursor to Marks & Spencer in 1884, it was more like the original Poundland than the aspirational store for the middle classes that it would become. “Don’t Ask The Price, It’s A Penny,” its slogan went. What it sold at the time wasn’t so much clothes as haberdashery, since most working-class people then made their own clothes.

1920s

The Marks & Spencer bra

Famously, in a 1987 television interview, Margaret Thatcher was asked if she loved Marks & Spencer underclothes “like the rest of Britain”. “Yes,” she said breathlessly. “Who doesn’t?” That quote from Thatcher, who was at the time one of the store's biggest promoters, sums up the long-running relationship there has been between the British public and the Marks & Spencer lingerie department. It’s a relationship that began in 1926, at a time when fleecy knickers were among their biggest sellers, when Marks & Spencer unveiled its first bra – a simple, functional item with a tiny pink bow at the cleavage. By 1953 M&S was selling 125,000 bras each week, and taking inspiration from American lingerie which used less boning for better comfort. It also introduced cup sizes, and by the 1970s staff were measuring customers’ bra sizes

1940s

Utility Clothing

Marks & Spencer’s experts helped design the ‘Civilian Clothing 1941’, or ‘utility’ scheme, which limited the amount of fabric, number of buttons and other elements to be used in clothing. But that didn’t mean the clothes were dull and drab – the opposite. As Katie Cameron, Marks & Spencer’s archive and outreach officer has put it: "You could only use a certain amount of fabric in a dress, but on the other hand there were fewer restrictions on dyes so we invested a lot in print design. As a result, you actually see a lot of colourful printed garments.” There was a vast array, therefore, of dazzling patterns from cowboys and ballerinas to Egyptian-inspired motifs.

1950s

The Princes Street store

On June 12 1957, the Edinburgh Princes Street store opened its doors for the very first time. The crowd of shoppers that turned up that morning was so huge that police were forced to split the queue into three parts before opening the door. According to sales records, “17 dozen summer dresses, 16 dozen blouses, 15 dozen children’s dresses and ten dozen nylon slips” were sold in the first hour. The store is still the busiest in Scotland.

1960s

Fabric technology

Those hair-raising, static-generating manmade fibres that were a feature of the 1960s and 1970s were often pioneered by Marks & Spencer. In fact, Simon Marks, who was the company chairman in the 1950s, said it was his mission to make the housewife’s life easier, making clothes that were much simpler to wear and wash. Courtelle, an acrylic, wool-like fibre, was first launched, in the UK, by Marks & Spencer during the 1960s ¬ as was Crimplene and Terylene. These fabrics were often drip dry, easy iron and held their colour or shape. They helped liberate women from domestic chores, while at the same time making Marks & Spencer look modern and part of the future.

“Fabulously beautiful, wonderful Terylene, made the St Michael way,” runs the jingle on a 1960s advert in which dancers, dressed in slacks, and skirts that have pleats that are “made to stay” perform a routine that looks straight out of a Hollywood musical. “Fashionable, washable," it added, "and always looks like new”.

Similar adverts exist extolling the virtues of Acrilan and Bri-nylon. “St Michael’s clothes in Bri-nylon are the dreams you can pack and take with you,” says a voiceover, as the film leaps between sunny Mediterranean locations. The new fabrics were aspirational, pitched as part of a life dream life that involved travel, glamour and smart cars. “Bri-nylon stretch swimsuits,” the voice goes on, “that keep their shape and yours in perfect trim. Styles as new as swimming in space."

The chilled chicken

Marks & Spencer set up a “cold chain distribution” system that meant prepared foods could be sold chilled, not frozen and our lives were changed forever. The chilled, rather than frozen, chicken was born.

1970s

Sell by dates

A revolution so crucial that when Marks & Spencer made their 125th anniversary advert they had Twiggy mention it. It’s now hard to remember a life before the sell by date – when people used to have to sniff a food, or take a guess as to whether a food was fresh and safe or not and anything that needed to be kept was frozen or tinned. Then the concept was created in the storerooms of Marks & Spencer during the 1950s, though it didn’t make its way onto the shelves until 1972. The sell-by date remains one of the most significant labellings of food, and the one that makes our entire food system possible.

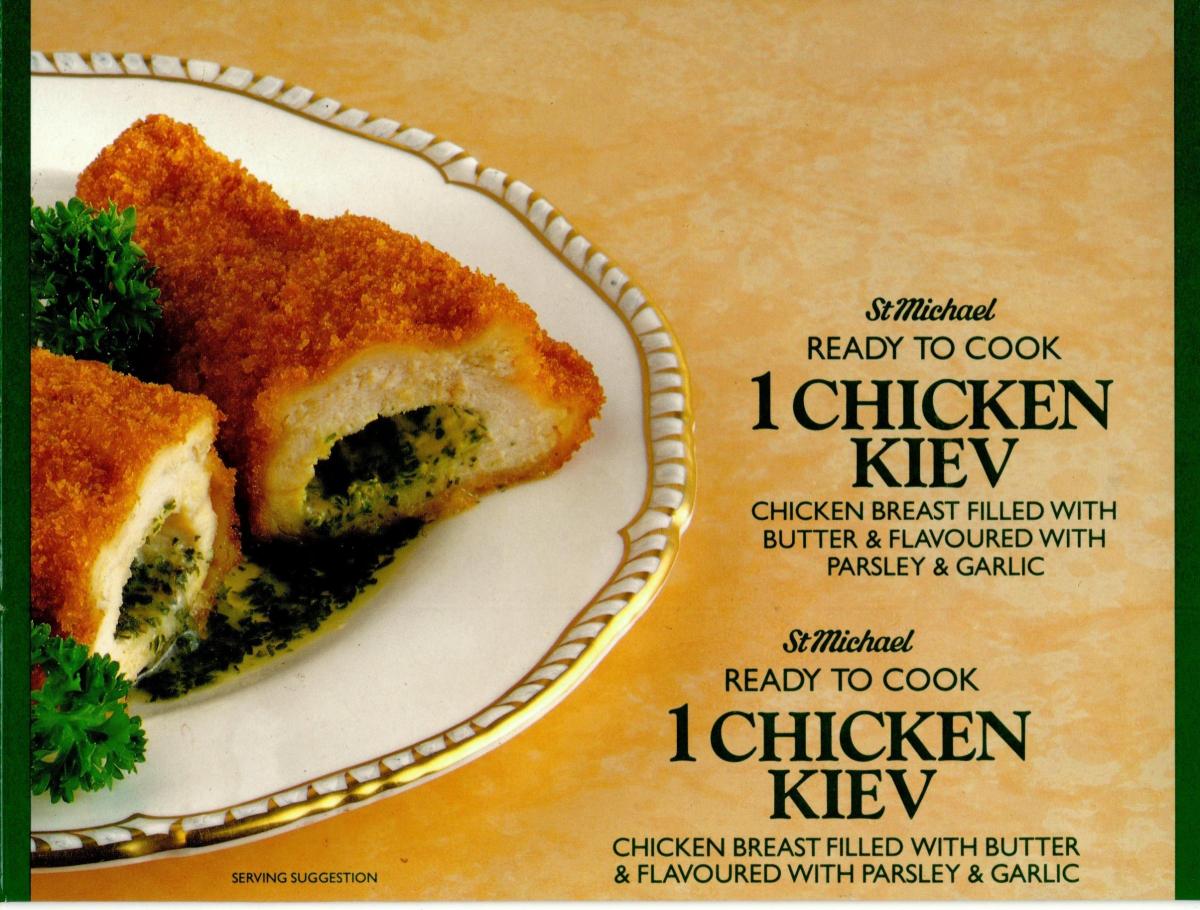

The Chicken Kiev

In 1979 the Chicken Kiev arrived and changed our food landscape forever. Almost impossible to make at home and irresistibly flavoursome, it was so popular it required a dedicated new factory. The TV dinner had been born and aspirational convenience food was on its way. "I remember very well thinking it was rather posh," the food writer Rose Prince recently recalled in an article in The Independent. "It seemed like something exotic and quite bistro." Behind this revolution was a chef called John Docker, who had given Marks & Spencer a call, suggesting that the British public was entitled to be able to buy restaurant-level food to enjoy in their own homes. The ball had started rolling. Come the 21st century what started with the Kiev would become a massive multi-billion pound industry. Currently half of the ready meals in Europe are sold in Britain.

1980s

The packaged sarnie

Back in the 1980s just about the poshest snack you could get was the M&S prawn and mayonnaise sandwich. In fact, the sandwich chiller at Marks & Spencer was just about as everyday aspirational as life got. if one thing changed our lives more than anything else, it was the supermarket’s invention, in 1980 of the packaged sandwich, or “sandwedge” as it has been called. The innovation came, almost by accident, when a few unsold sandwiches from the café in the Marble Arch store were packaged up and sold, but soon it was being rolled out throughout the country. The Edinburgh Princes Street store was one of the first to trial it, with staff constructing sandwiches in a stockroom. Since then we’ve turned into a packaged sandwich nation - eating £3.5 billion worth of the things a year.

The Thatcher years

Margaret Thatcher and Marks & Spencer seemed a marriage made in capitalist heaven, and the prime minister wasn’t shy about bigging up her favourite store. “I do go to Marks & Spencer quite a lot,” she said in one 1987 television interview, “Or they kindly send things in. They’re marvellous. Their cut is excellent and they’ve now got all kinds of colours.” But the connection was about more than taste, or supporting British retail. Lord Sieff, the last of the actual Marks & Spencer dynasty, was also one of Thatcher’s heroes, a man who had taken his family business to new heights of retail success. Sieff also backed the Conservative Philosophy Group.

1990s

The M&S party bite

Who needed to spend hours slaving over a blender to create the perfect hummus or salmon mousse, when you could just dash into your local Marks & Spencer and make them provide the party for you? Ready made food wasn’t just about ready meals, it was about entertaining – particularly for the hard-working, hard-partying, metropolitan Bridget Jones set. In one of author Helen Fielding’s columns, Bridget describes her friends coming round with M&S food – “one tub hummus & pkt mini-pittas, 12 smoked salmon and cream cheese pinwheels, 12 mini-pizzas, one raspberry pavlova, one tiramisu (party size) and two Swiss mountain bars” - which they eat while debating “emotional fuckwittage”. The column was a sharp portrait of casual entertaining in aspirational 1990s Britain.

Peak Sparkle

This was the decade when Marks & Spencer reached peak success, making over £1bn in pre-tax profits in 1997 and 1998, but also began its downward slide. Back in the early 1990s it was even cool to wear Marks & Spencer clothes. The Rise and Fall of Marks and Spencer cites Vicki Woods, the former editor of Harpers & Queen, describing how back then, her young staff would spend afternoons in M&S. They were “rootling through every garment in the store, looking for the M&S star purchases: the things that looked as though they came from Bond Street but sold for a tenth of the Bond Street mark-up.”

Noughties

Food Porn

“This is not just a chocolate pudding. This is a melt in the middle Belgian chocolate pudding served with Channel Island cream,” drooled Dervla Kirwan in a voiceover so sultry that it felt like it belonged on some 1970s soft-focus porn. Nigella Lawson had already made this kind of sexy delivery her trademark, but Marks & Spencer took it and made it sell food. The advert sent the chocolate pudding sales soaring. This wasn’t just food porn, it was an M&S food porn advert.

Bye bye St Michael

Something started to go wrong. Was it that clothes weren’t right? Was it that Next seemed to have seized grip on the clothing market in the UK? Was it that there was a new breed of supermarkets emerging on the British high streets? Was it that using British suppliers, rather than goods imported from low-cost countries like their competitors, was too much of a burden? Probably it was all of these things, and many more. The store switched to overseas suppliers. It dropped its iconic St Michael brand, and replaced it with 13 others. But the slide kept happening. Then, the financial crash came in 2008, hitting Marks & Spencer particularly hard.

2010s

The miracle skirt

In 2015 the Marks & Spencer story was all about the skirt that saved the company and jump-started the first rise in profit in four years. The skirt, for those who don’t remember it, was mid-length, suede and brown, and probably would have gone unnoticed if it were not for the fact that style guru Alexa Chung was photographed wearing it. But Chung and the publicity around the skirt performed a miracle and in May, when it went on sale, it quickly sold out. However, some were not convinced. The Guardian's Hadley Freeman claimed the skirt represented "a triumph of M&S PR over actual fashion for women".

Stuck in the middle

The last eight years have only brought relentless bad news stories from the supermarket, the latest of which has been that they are to close 100 stores by 2022. There are many reasons behind this – one of them being that other companies are doing aspirational food very well. In 2014, sales at John Lewis and Waitrose overtook those at Marks & Spencer.

One idea that is often cited as part of the problem is that Marks & Spencer is caught in the difficult middle ground of retailing. People are going to them just for occasional treats, while exploiting the bargain deals for other products at Lidl and Aldi, or fast fashion chains like Zara and H&M. “M&S is the literal middle of everything,” wrote Mark Ritson in Marketing Week. “It emerged from the middle of the country, as a Jewish peddler travelled the cities of England selling his wares ... It priced itself in the middle. It offered a middle level of quality above the traditional fare but below high-end, exclusive products. It even established its sales associates as somehow between the standard shop girls that populated stores in the mid-20th century and the snooty sales people of the high-end department stores. But the middle is no place to be anymore.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here