JEREMY PEAT

Remarkable though this may seem to those who have regularly read this column in recent months, pessimism is not my natural mode. I do not enjoy a good dose of doom and gloom; having reasons to be positive and optimistic would cause me great joy. But alas no such reason has appeared - even upon the distant horizon.

When economic historians examine the present era with the benefit of hindsight it is hugely likely that they will see the UK’s decision to leave the EU as a major folly; and to enter into Brexit negotiations with no strategy and no coherent plan masochistic in the extreme. The adverse implications will be seen as adversely impacting the economy of the UK for distinctly more than one decade.

Of course we still have no real idea as to how the UK will exit the EU; nor indeed do our negotiators. At least the Labour Party has now come out with the beginnings of a credible policy, accepting that maintaining arrangements for trade, etc. on an interim basis would be preferable to some leap into the unknown. However, the UK Government still seems fixated with the view that ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’, when leaving with ‘no deal’ would be disastrous for business and the wider economy.

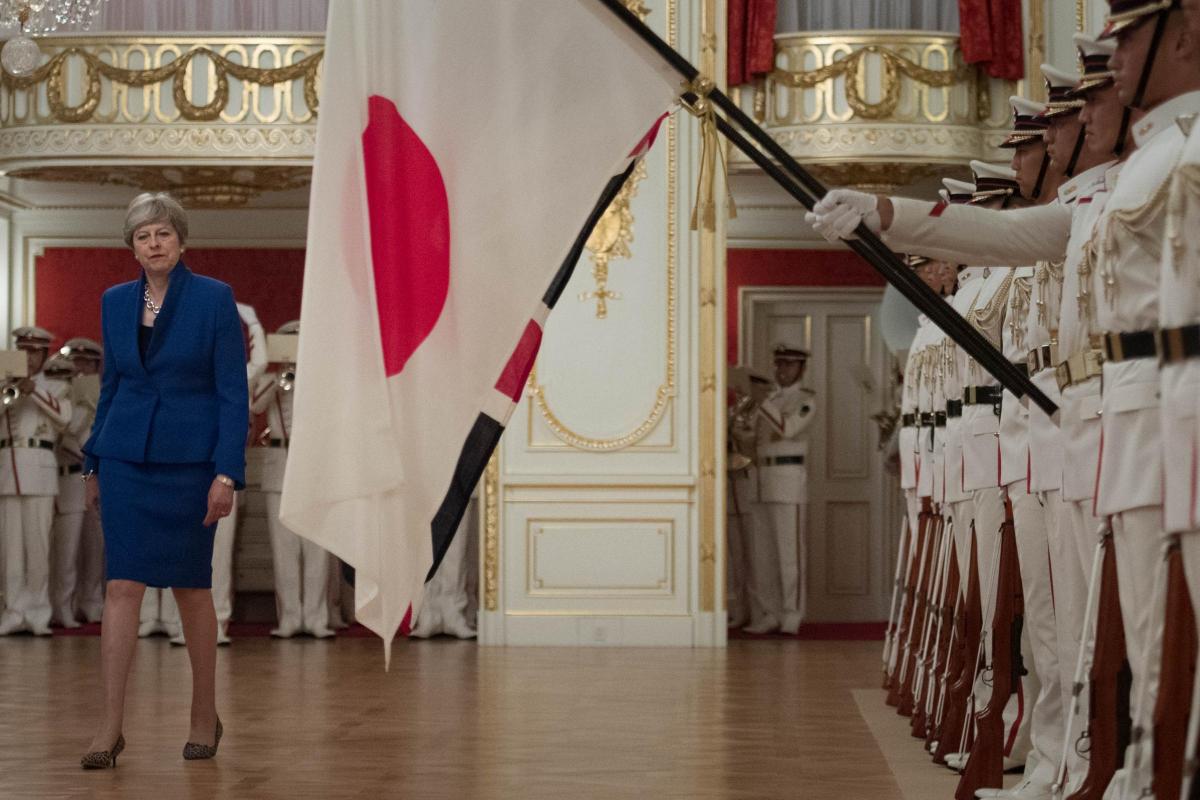

Further, the idea that the UK can somehow negotiate trade deals with other nations in advance of finalising arrangements for EU exit is now being shown as a false hope. Japan is the latest of our major trading partners to indicate that this option is not on the table. Given the scale of Japanese inward investment and the importance of Japanese companies with bases here, the lack of agreed arrangements with Japan for trade and investment would be another major blow to our economic prospects.

The impact is not solely on trade and investment. The SCDI and various employers and employer organisations have stressed the importance to the Scottish economy of labour from the EU and elsewhere. The sectors involved are many and varied – from low skill input to agriculture, to medium skills in tourism and various trades, to high skills in academia and financial services. These people are critical to so much within our economy.

The latest migration data show, understandably, many more citizens from elsewhere in the EU leaving the UK; and far fewer EU citizens entering. In part this will be due to the impact of sterling’s sharp depreciation, a result of the Brexit vote, on the financial value (in euro terms) of employment in the UK. In part it must be due to the huge uncertainties surrounding the future for nationals from elsewhere in the EU so far as a career in the UK is concerned. Anecdotal evidence from a variety of sources confirms this view.

In sum UK’s exit from the EU will have adverse effects on our economy; and the uncertain manner of our exit is aggravating the impact and causing major issues even before our due departure date. Given the apparent mounting hostility between our negotiators and those from the EU, the short term concerns and uncertainties are likely to get worse before they get better. Meantime the prospects of a managed exit, with a close eye on minimising the downside, are reducing day by day.

It is unsurprising that under these circumstances consideration should be given to leaving the UK rather than the EU. Unfortunately the latest data from the annual report on Government Expenditure and Revenue for Scotland – for the financial year 2016-2017 – points up the problems this would pose so far as our public finances are concerned.

This report once more demonstrates that, at least in this continuing period of relatively low oil prices, Scotland has a far higher deficit in the public finances than is the case in the UK as a whole. The deficit figures are slightly lower than in 2015-16 and can be presented in a variety of different ways, but the conclusion is inescapable. Scotland’s deficit is markedly higher than could be entertained on a continuing basis for an independent nation with its own currency; and far higher than would be permitted for a nation set on entering the eurozone.

The cause of the ‘excess’ deficit is not that tax revenue is relatively low, but that public expenditure is relatively high. Revenue per person in Scotland was just under £11,000 in 2016-17 as compared to just over £11k for the UK – a gap of just over £300 per head. But ‘managed’ public expenditure per head was £13,175 in Scotland as compared to £11,739 for the UK – a difference of over £1,400.

As has been well rehearsed elsewhere, there are essentially three ways of reducing the deficit. Taxation per head could be increased, albeit this is not tackling the prime cause of the excess and might have the immediate impact of slowing GDP growth. Or expenditure could be reduced, which would be difficult to achieve to any marked extent without hitting health or education and without adverse effects on welfare. Or the rate of growth could be enhanced, leading to increases in revenue over due course and hence deficit reduction.

This last solution would clearly be optimal but would take time and reductions of substance in public expenditure would be needed in the interim. It is also by no means certain that faster growth can readily be achieved. That is why the First Minister set up the Productivity and Growth Commission under Andrew Wilson. We need their much delayed report as a matter of urgency – both to attempt to minimise the continuing impact of Brexit and to see if realistic options can genuinely be opened up for the future. I very much look forward to reading what Andrew Wilson has to say.

Jeremy Peat is vsiting professor at the University of Strathclyde International Public Policy Institute.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel