WE are probably going to hear a fair bit in coming months about the squeeze on household finances easing as inflation likely edges down from its recent highs and nominal pay settlements perhaps pick up a little from a low base.

However, it will be crucial to keep any such narrative in context.

If annual UK consumer prices index inflation does continue to fall back towards its target, it is important for people to keep in mind the basic point that the surge in costs which households have already seen because of sterling’s post-Brexit vote weakness is not in any way being reversed.

We are not talking about deflation. The expectation is that prices will continue to rise but hopefully at a slower annual pace.

The damage that has already been done to household finances from the Brexit vote folly is therefore a permanent, and not a fleeting, thing. Blustering Conservative politicians must grasp this fact.

Read More: Ian McConnell: Amid awful Brexit xenophobia, facts on immigration may make no difference

High inflation is one key reason why the UK now finds itself at the bottom of the pile of major advanced economies in terms of recent and forecast growth.

Annual UK CPI inflation was just 0.3 per cent in May 2016, ahead of the ill-judged Brexit vote. By November last year, it had climbed to 3.1%. It had by February eased to 2.7% but this is still way above the 2% target set for the Bank of England by the Treasury.

After the Brexit vote, given sterling’s consequent weakness was always going to propel import costs higher, it looked inevitable the Bank of England would find itself having to deal with an unhelpful mix of weak UK growth and high inflation. And so it has proved.

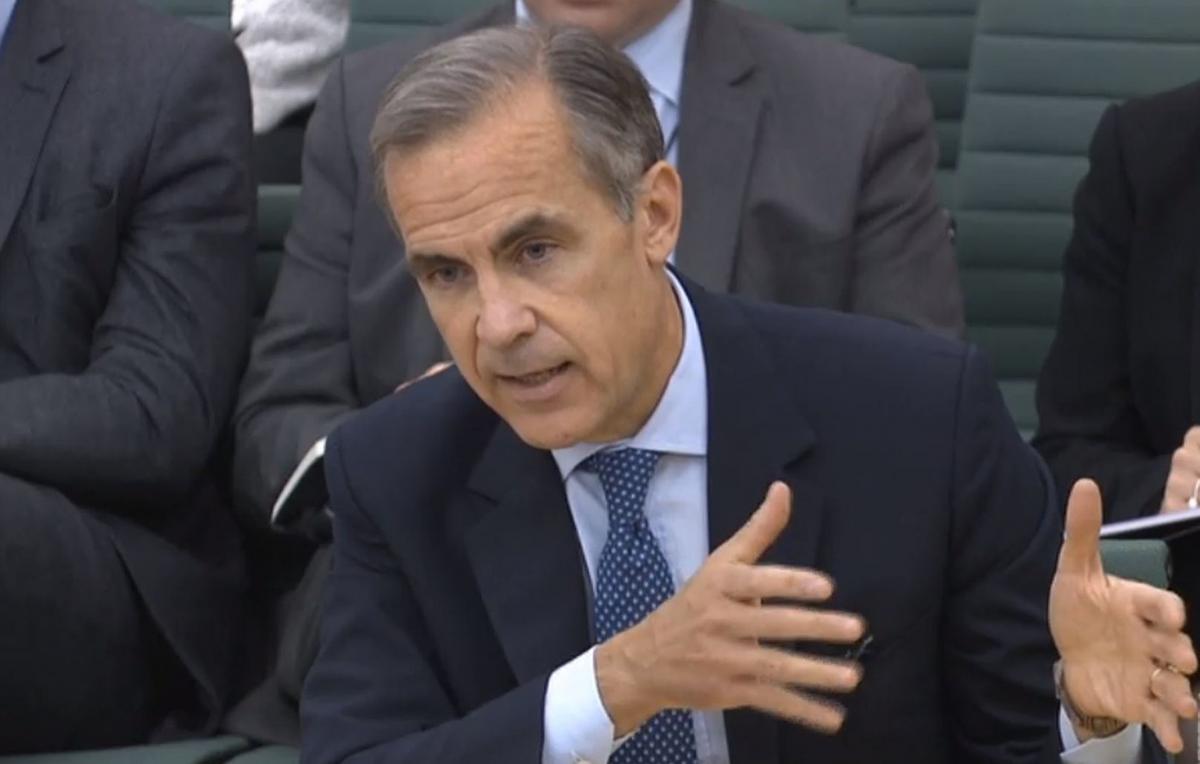

It is an unpalatable combination indeed. And the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee has signalled that, in spite of weak growth and fragile consumer confidence, further rises in interest rates will be needed in coming months to bring inflation back towards target. Bank Governor Mark Carney has, quite rightly, made it plain the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street cannot be expected to offset all of the negative impacts of Brexit.

The MPC raised UK base rates by a quarter-point from a record low of 0.25% in November last year – the first increase in more than a decade.

Read More: Ian McConnell: Brexit theme park would be so much cheaper than this costly fiasco

Economists predict a further quarter-point increase in May, when the Bank produces its new growth and inflation forecasts, and more to come by way of higher benchmark borrowing costs later in the year.

Expectations of a May rate rise were fuelled by minutes of last month’s MPC meeting. These showed two MPC members, Ian McCafferty and Michael Saunders, voted in vain for an immediate quarter-point rise in rates on March 21.

Read More: Ian McConnell: Talk of Brexit ‘betrayal’ is cause for fear among firms

Referring to Mr McCafferty and Mr Saunders, the minutes state: “These members noted the widespread evidence that slack was largely used up and that pay growth was picking up, presenting upside risks to inflation in the medium term.”

The other seven MPC members believed the May forecast “would enable...a fuller assessment”.

While there may be some signs that pay settlements might be improving modestly, we should not get our hopes up too high on this front.

The labour-market shortages created by the plunge in net migration to the UK from other European Union member states seem likely to put upward pressure on pay. These shortages have been highlighted by a raft of sectors, from hospitality to information technology.

However, we are also in an environment in which employers are understandably worried about the implications of Brexit, and this would seem likely to augment their usual reticence on pay, particularly given the grim UK economic backdrop.

With employee rights and union power having been eroded seriously in recent years and decades, many workers would also seem likely to be nervous in the current environment about pushing too much for some better pay rises. Even though such a push would be justified, given many of them have seen their real pay eroded for the vast bulk of the period since the global financial crisis around a decade ago.

And that is even before we get to the misery of the public sector workers. Many of them are rightly pushing for a decent rise in earnings after years of public sector pay caps imposed by the UK Government, but they are facing strong headwinds and look to have their work cut out.

All of this means the pressure on household finances, even if inflation does fall sharply, will not be easing meaningfully any time soon.

Other factors will also be weighing on people’s appetite to spend, notably the growing awareness among many employees that their pensions are going to be far inferior to those of the baby boomers.

South of the Border, the hike in university tuition fees implemented by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition from 2012 will continue to hit the finances of many tens of thousands of households.

All the while, we have the continuing prospect of the UK remaining a laggard among the major developed nations in terms of growth, as it is weighed down by Brexit.

The current spate of casualties and closures on the UK high street, taking in big-name retailers and restaurant chains, highlights the pressure on consumers. This spate is about far more than changing shopping patterns amid the online revolution or altered dining preferences.

At a time when households are having to deal with falling real wages and economic dangers loom large – and the sight of any catalyst that might change their fortunes remains as elusive as ever – consumer-facing businesses such as retailers and restaurants will bear the brunt.

Employees in Great Britain experienced another year-on-year fall in regular pay in real terms in the three months to January, latest official figures show.

The Office for National Statistics said average weekly earnings in the November to January period were, excluding bonuses, down by 0.2 per cent on a year earlier in inflation-adjusted terms. In nominal terms, regular pay in the three months to January was up by 2.6% on a year earlier. This was only a marginal improvement on nominal year-on-year pay growth of 2.5% in the three months to December.

Time will tell if nominal pay growth picks up further. However, even if it does, and inflation falls, households will be having to deal with the significant impact of higher interest rates on the cost of servicing mortgages and elevated unsecured debt. And with all the other pressures on their finances.

Hopefully pay will stop falling in real terms in coming months. However, any claim by the UK Government that this means the pressure on households has eased in any significant way should be taken with a tonne of salt.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel