TO SOLIHULL and back. The road to Jamie Murray’s personal and professional fulfilment has been pockmarked by lazy comparisons and diverted significantly by one wrong turn. He seemed to be trapped in a professional cul-de-sac. Two years ago he was running out of road. He makes his debut next week at the lucrative Barclays ATP World Tour finals in London and he is scheduled to play a crucial role as Team GB contest the Davis Cup final, the world cup of tennis. Reaching 30 next year, he is at the height of his career, rated the seventh best doubles player on the planet and contesting two grand slam finals this year.

So how did a career that seemed to stall kick into raucous life? Why and how did a disillusioned Murray, contemplating an irrevocable break from the game, embark on this most spectacular run? How did a sportsman, seemingly condemned to being referred to as “Andy’s big brother”, carve a niche for himself at the elite level?

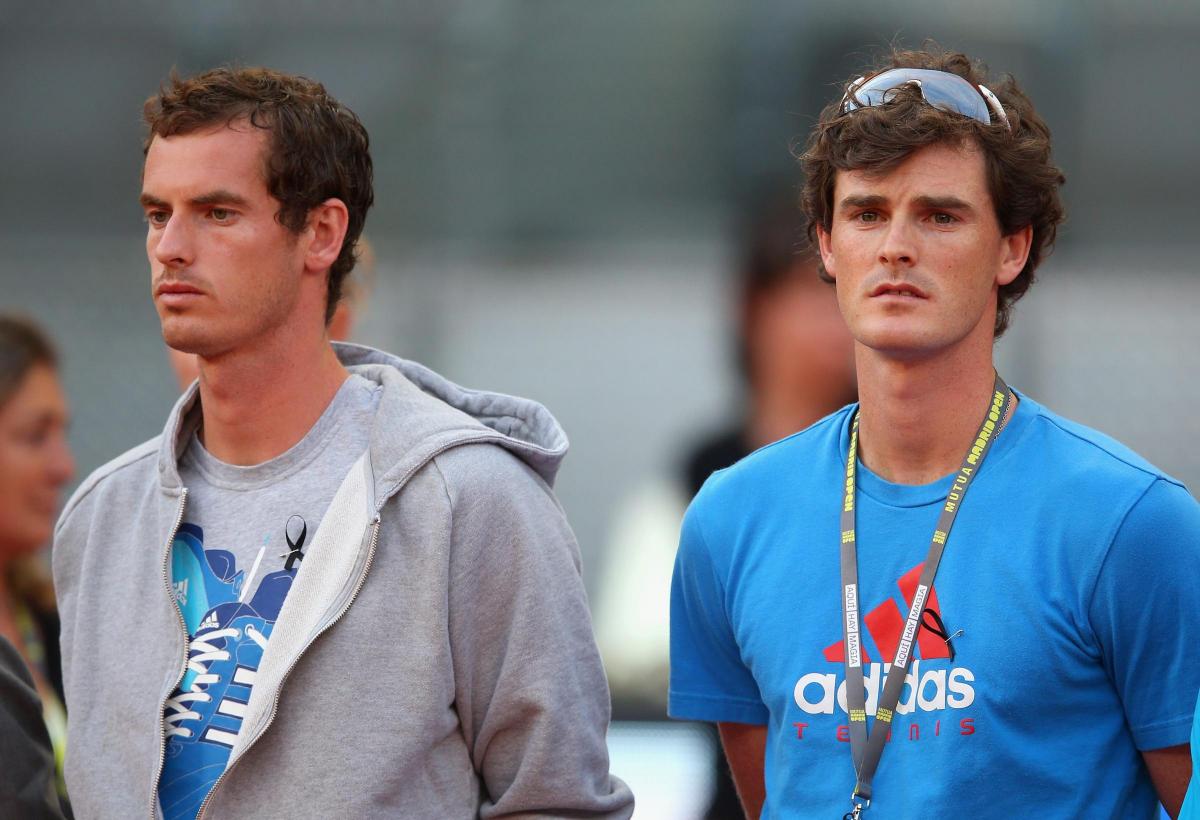

Boys to men: the Murray brothers' journey in pictures

The answer lies in a moment of reflection in Melbourne two years ago. “I was not sure I wanted to keep going,” he says. He had departed the Australian Open tournament in the first round. Grand slam finals seemed merely a dream, if not a cruel mirage. Yet this season he has reached the finals at Wimbledon and Flushing Meadows. Twice as many grand slams this year as his younger brother, I point out. “I have kept quiet about that,” he says. “I am not sure I am going to win that argument,” he says of a brother who has won the singles championships at Wimbledon and Flushing Meadows and has struck Olympic gold.

Jamie and Andy, of course, were once not so careful about choosing grounds for battle. Their competitive instincts were highly honed, perhaps by innate personality, certainly by genetics. Their mother, Judy, was a Scottish tennis internationalist. Their father, Willie, was a combative Junior footballer. As the brothers stared at each other in the aftermath of a doubles victory in Glasgow in September in front of 8,000 spectators that led to Ghent and the Davis Cup final, there was an evident bond. Sparks flew, though, as that link was forged down the years.

The Murray family: Jamie and Andy with mum Judy

And that brings us to Solihull. “We were on the way back from a big junior tournament. Mum was driving the minibus and he [Andy] had beaten me in the final of the under 10 or under 12 or something and he was giving me stick about it. I turned round and grabbed his arm rest. I banged his hand with it. His nail did not recover for years and probably still if you look at it now is not completely like the rest of them. A little reminder for him not to mess with me,” he says. The last is said with a chuckle but the story blows away the theory that Jamie was hampered fatally by a lack of competiveness, the sort of drive that thrust his brother into the elite rank.

Jamie’s progress was not constrained by a lack of desire. He went in the wrong direction but for the best of reasons. A conspicuous talent, rated as one of the best youngsters, he more than held his own in an age group that included Rafael Nadal and Richard Gasquet.

At 12, he left Dunblane for Leys School in Cambridge to attend a Lawn Tennis Association course. He was supposed to take part in the scheme at Bisham Abbey National Sports Centre but that fell though and Jamie returned home after eight months. “I feel that I was not the same player after that experience,” he says. This is said without bitterness. “I maybe was a bit overwhelmed by it all." He was, of course, just 12. He later watched Andy take a similar journey, this time to Barcelona.

Professionally the boys came to a fork in the road. Andy raced into the elite, becoming part of the Big Four of Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic and Nadal. Jamie became a doubles player. His most conspicuous success came when he won the mixed doubles at Wimbledon with Jelena Jankovic in 2007. But in the subsequent years he seemed to have more partners than a dancing host on a Saga cruise liner. But just where was Jamie heading?

HE pauses, but only briefly. “The lowest moment?” he replies. “That would be at the Australian Open two years ago. I played with Colin Fleming and I had a terrible match. We lost in the first round. I had a ranking draw of about 75 in the world, I did not have any partner. I did not have any direction going forward and I was not sure I wanted to keep going.

“I was playing with loads of different people, sort of wandering from one tournament to the next. I did not quite know where I was going. I was despondent about how things were going. There seemed no plan, no direction. I was not sure I wanted to go along the same path.”

He was at a crossroads. He was married happily to Alejandra, a Colombian. The travel was tedious, the present gloomy, the prospects dim. He talked with those around him, including a family well aware of the brutal realities of modern tennis. One close associate told me: “Basically, he decided to invest in himself.”

It paid extraordinary dividends. The first, most important development was his decision to commit to a working partnership with John Peers, a 27-year-old Australian. They almost immediately tasted success, beating 13-time Grand Slam champions and world No1 pair Bob and Mike Bryan in the final of the US Men's Clay Court Championships after coming back from a set down. “It was fortunate that JP came along at the right time and we were able to make a go of it,” says Murray.

This link-up may have an element of fortune in it but there was purpose to other significant moves. He now works with Dr John Mathers, a sports psychologist at Stirling University. “This has definitely helped. I do not want to go into too much detail about what we talk about it but it is nice to get someone else’s input. I have known him since I was very young and he is one of the reasons why I have headed in the right direction and why my performance level has been a lot higher and more consistent.”

Another significant contribution has been made by Louis Cayer, routinely described as the best doubles coach in the world. Cayer travels with the Davis Cup team and Jamie, who has worked with the Canadian extensively over the years, has been able to tap into his expertise. Jamie’s game has always been technically sharp. Left-handed and with a gangling, sprawling frame, he is a distinct presence at the net. His volleying is peerless, his ability to make and profit from angles is part instinctive, part a result of experience and inspired coaching.

The journey from Melbourne 2013 has been rewarding. He and Peers have won six ATP titles, Murray has achieved his highest ever doubles ranking. The tour finals in London beckon. It will also serve as a farewell to the partnership. Jamie will play next year with Bruno Soares, a Brazilian ranked higher than Peers. The trajectory is ever upwards.

The Davis Cup has been an extraordinary bonus with Murray playing a huge role with his brother in winning against France and then against Australia. Jamie, with the stereotypical mindset of the elite athlete, wants more. “I am not yet 30 and I believe the best is yet to come. There are guys still playing at the top of the game in doubles into their forties. With the scoring system, matches can be an hour to an hour and a half long. OK, there are five-set matches in the Davis Cup and in some grand slams but physically, in most tournaments, it is not that taxing. The endurance aspect is not here any more. But every point counts in the doubles so it is stressful. It can invariably come down to championship tiebreaks for money and ranking points. Basically, it becomes a shoot-out for your professional life. That makes demands on you mentally and it tests your technique because you have to make difficult shots in the big moments.” Murray has stood up to this. He has won half a million dollars this year, taking his earnings to more than £1m since he turned professional in 2004. He says: “I have worked hard and I understand my game style and I know how to use it to my advantage. Experience helps. I know what it takes to perform well.”

HIS finest hour comes with his brother. On home turf, or rather hard court. The year of 2015 has witnessed Jamie reaching two grand slam finals but nothing can prepare him for September 17 and the febrile atmosphere of the Emirates Arena in the east end of Glasgow. Andy and Jamie are walking out on to court to face Lleyton Hewitt and Sam Groth in the doubles rubber. Given Andy’s dominance in the singles, a victory for Team GB in the doubles almost guarantees them a place in the final against Belgium. Just short of four hours later, the brothers hug after a five-set match that induced a benign form of delirium in 8,000 supporters.

“It was quite surreal,” he says. “We walked out on the Saturday with Leon [Smith, Team GB captain] and the ovation was amazing. That was a ‘take stock’ moment. When we started out, of course, our parents did not expect us to get where we are – why would you? Scotland had no history of tennis really – but here we are. Hopefully there are kids who will follow in his [Andy’s] or our footsteps.”

Jamie is doing his best to ensure that eventuality occurs. He is passionate about doubles and has launched the Jamie Murray Doubles Cup that seeks to bring youngsters into tennis. He knows doubles is the bedrock of the club game and he is passionate too about the fun and enjoyment it can bring.

It has, however, brought him even more. In the run to the Davis Cup final he has been involved in three extraordinary matches. With Dom Inglot, he took the Bryan brothers to five sets at the Emirates, then with Andy defeated the French pair of Jo-Wilfried Tsonga and Nicolas Mahut in a colossal struggle at Queen’s Club in London. It was inevitable, perhaps, that the showdown in the semi-final with Hewitt and Groth should be similarly spectacular.

Andy, with his two grand slam victories and his eight appearances in major finals, might be expected to be accustomed to the pressure but how does Jamie cope with this noise, this hype, this glare of publicity, this atmosphere laced with expectation? “Yes, I have been thrust in to the limelight,” he says. “The Davis Cup noise levels are extraordinary and so different to tour events. Sure, there is pressure but I feel more proud of myself of getting through these matches because of that. For me, the makeup of our team shows how important the doubles is.”

Basically, the expectation is that Andy will win both his singles rubbers and a successful match for the doubles team gives GB a victory. This places an extraordinary burden on the younger Murray. But it also makes demands on the big brother. “There is the expectation but, to be honest, I do not really think about it, certainly when I am playing,” says Jamie. “You get caught up in the moment. I grew up wanting to play tennis. I wanted to play at the highest level. I wanted to play on the biggest courts in front of the biggest crowds. This is the reward for all the hard work, all the sacrifices. I enjoy it. I enjoy showcasing my talents because most of the year I am competing in front of smaller audiences on a smaller scale.”

But what of playing with his brother? “I have great respect for what he has done as a player,” he says. There has never been a word of envy uttered by Jamie at his brother’s success. “I love seeing him win. I know what he puts into it and how hard he has had to work for everything,” he says.

But is he focused on what Team Murray is about on Team GB duty? “It is funny but we do not look on the match as a family affair or anything. We are totally concentrated on playing the best we can. We are playing for the team, not each other. We are playing for everyone on the bench and everyone who comes out to watch.” But there is that undoubted bond. “I knew and Andy knew against the Australians and against the French that we would give each other all we had, we would go all out. We enjoyed being in the battle with each other and that is what pulled us through in the end.”

There was a fraternal hug as they reached the Davis Cup final to a soundtrack of the Emirates roar. “It was a tough match and swayed towards the Australians at one point. The emotion for me at the end was not the undiluted joy of success but a sort of relief and satisfaction. It was a sort of: ‘Thank God, we got through that.'”

And does that competitive spirit of Solihull still exist between the brothers? “Yes, maybe, but not to the point where we are hitting each other in the back of cars,” he says. “We are competitive – always have been, always will be. We have the same blood.” The evidence of that is persuasive. It can be witnessed on a tennis court and was once smeared on a mini-bus arm rest.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel