IN the April of 1951 a salesman, newly arrived in Edinburgh from London, was trying to find a certain wine and spirit merchant in Elm Row. He had been walking up and down the street, frowning as he checked off the street numbers.

It was the smell of roasted coffee that alerted him to the shop he was after: a delicatessen, which happened to be closed for lunch. When it re-opened he entered the long, narrow, busy store of Valvona & Crolla, every last inch of it put to some purpose. And the distinctive blend of smells … coffee, brie, fresh bread, mortadella, ham. Spices, too: cardamom, chilli, paprika, saffron. From overhead dangled sizeable strings of salami and pork sausages, dripping onto the sawdust scattered across the floor.

“There’s not so much modern air-conditioning in Elm Row”, reflects Mary Contini, a director of the company, “so the smells accumulate and linger. There are coffee beans, and there’s cheese being cut, and it has an impact. It’s a seasonal thing, too”, she adds. “Just now we have peaches and strawberries. In about two or three weeks we’ll start to get the truffles in: the place will start to fill with the smell of white truffles from Alba, and that takes on a lovely headiness of its own”.

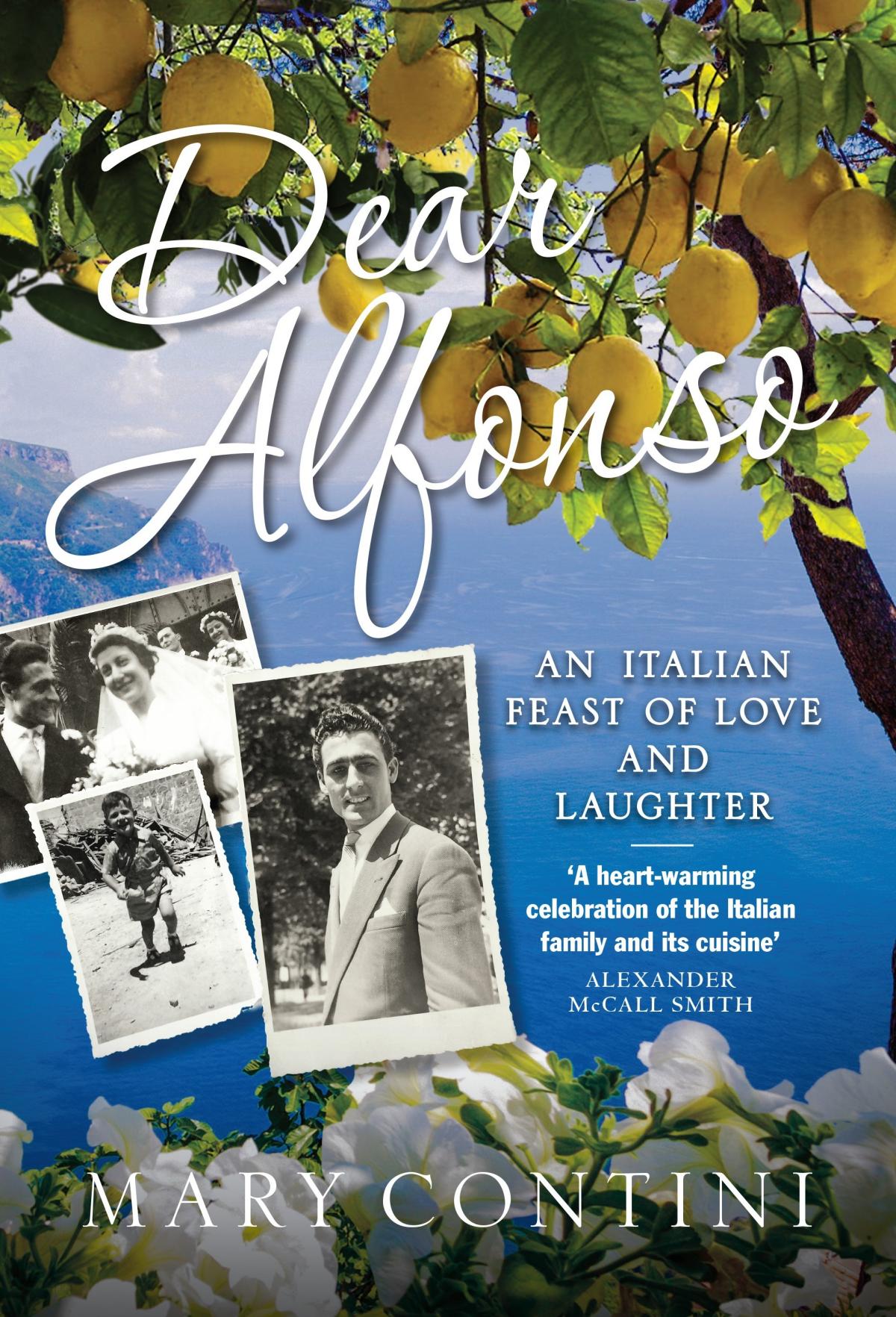

Contini is sitting at an outdoor table at Valvona & Crolla’s VinCaffe in Multrees Walk, ten minutes’ walk from the Elm Row deli and Caffe Bar. We’ve got onto the subject of the smell of food because it crops up often in Contini’s latest book, Dear Alfonso, which tells the story of her enterprising father-in-law, Carlo. Born into poverty in the old fishing port of Pozzuoli, near Naples, he came to Scotland in 1952. He met, fell for, and married Olivia Crolla, and became part of her family’s business, Valvona & Crolla. The book is based on a long-forgotten manuscript of his, addressed with gratitude to someone he had never met – Olivia’s father, Alfonso, who had died in 1940 as an enemy alien - arrested, imprisoned then deported - aboard the Arandora Star, which was torpedoed by a German U-boat and sunk off Ireland with the loss of some 700 lives. Carlo himself died in 2008.

The book reminds you of the startling extent to which food is Italy’s defining passion. As Jamie Oliver observes in his book, Jamie’s Italy, Italians spend ages “arguing about where the best stew is from, or the best pappardelle, or olive oil, or seafood … they’re not being aggressive – they’re simply arguing their point!” The inhabitants of one village will argue that they make a certain thing in a perfect way and look with contempt at another village’s method, he adds.

This attitude towards food also comes over strongly in Contini’s book, as does the Italians’ love of shared mealtimes. “They say in Italy, the Pope and king – when there was a king – ate the same food as the peasants,” she says, “because the food that is eaten is of the earth and of the season, and it’s still the same.

“It’s very regional. One village will eat a different meal from the next, but to the same standard. The press has said that Italy’s food is changing, and that supermarkets have had a big impact, but in our experience, in our homes, there’s still the yearning to eat properly, to eat what grandmother used to make.

“So that habit is not lost – though maybe, if you’re a tourist in Italy, it’s harder to find. But there’s been a resurgence for example, in Sicily, where the food is so fantastic: the restaurants are enjoying a revival and you get fabulous fresh seasonal food served there now. Venice is fabulous as well”.

Contini’s earliest food-related memory is an interesting one. “I was about four, and I was at the table in my own home, which was above an ice-cream and fish-and-chip shop in Cockenzie”, she says. “I remember distinctly that when my older brother and sister were taken away to school, I went round to see what food was left on the table and scooping it all up.”

Another food memory: on Sundays her paternal grandmother, Marietta Di Ciacca, “would make sugo [pasta tomato sauce], home-made pasta, roast chicken, stuffing chicken with ricotta and pecorino … all these traditional dishes, from scratch, and that’s what we grew up with. It was great.

“There was always plenty of food. In Naples, no matter what was on the table it would be shared among everyone who was seated around it.

“When I went to Naples 40 years ago, when I was first married, Vincenzo, Carlo’s brother, was the host. He would sit at the head of the table and say, ‘Come in and sit down’ to anyone who arrived at the door. It’s part of the message of the book: with people who have nothing, the sharing of food with family is natural.

“Carlo’s mother, Annunziata Conturso, used to say that as soon as people got refrigerators, they used to hoard food, so rather than buy for the day they would buy extra, and end up throwing it out”.

With the rise in popularity of takeaways, ready meals and frozen meals, and snacks consumed on the go, some might think that in Scotland we’re straying far from the way Italians celebrate food. Contini disagrees. “I think we’re further ahead than we have ever been”, she says. “There’s more available. If you look round every town there’s far more food specialisms, people enjoying selling food or trading in it. There are farmers’ markets everywhere.

“I’m down on the coast [at North Berwick] now, and there’s a lobster shack on the beach. So people are really interested. They have a natural appetite”.

A recent Cancer UK survey found that consumers across Scotland choose cut-price items with sugar content equivalent to almost 110 tonnes of sugar every day. Contini is convinced that if we can wean ourselves off sugar and eat three meals a day, “you actually get more pleasure out of your food: you don’t feel hungry. That’s a big change that will make a difference”. She recalls the government assaults on smoking and is encouraged that sugar has begun to be targeted.

Fast food is popular in Italy, too, of course. In Via Toledo, the ancient main street of Naples, the current fashion sees people queuing for chips. The chips are served with squid or sprats, and they’re walking out the door. There’s a striving street-food scene, which means you can graze all day long, should you wish.

The recipes in Dear Alfonso, some of which are reproduced here, are from Carlo’s mother, Annunziata Conturso. Her philosophy was very much one of making delicious meals for a large family on the tightest of budgets: wasting food would have seemed like a grave offence. Bread salad; spaghetti with fish-head sugo; rice with mozzarella: in these recipes, you realise, is the story of a family – and the stories of millions of families just like them.

The bestselling American novelist Jonathan Safran Foer once said “stories about food are stories about us – our history and our values”. It’s an interesting quotation.

“I think that’s absolutely the truth”, says Contini. “Our greeting in Italy is ‘hai mangiato?’ – ‘have you eaten?’ – because you have got to survive before you can do anything, before you can think. Before you can have energy to do anything, you need to eat.

“My daughter Olivia has been studying Chinese in China, and when she first went there she was absolutely amazed because it felt like Naples. Everybody is interested in food, all day long. They don’t say to you when you meet, ‘How are you?’ – they say the equivalent of ‘hai mangiato?’. And I think that’s fundamental”.

She laughs as she adds, “But here in Edinburgh, of course, they say, ‘You’ll have had your tea’…

”

Dear Alfonso: An Italian Feast of Love and Laughter, Birlinn, £17.99, is published on Thursday. Mary Contini will appear at the Wigtown Book Festival at 3pm on Sunday October 1, www.wigtownbookfestival.com

Annunziata Conturso's family recipes

Rum Baba

Annunziata never made cakes. As is common all over of Italy, patisserie and gelato are bought as treats in specialist bakery and ice cream shops. Try these baba, but it may be better fun to take a flight to Naples and go straight to the Piazza Trieste e Trento: take a table in the Gran Caffe Gambrinus, sit in the historic painted tea room and enjoy with a glass of Cinzano on ice.

Makes 12 baba

250g strong bread ?our

100g unsalted butter

10g fresh yeast or 5g dry yeast

5g salt

4 eggs

15g sugar

For the syrup,

juice of ½ lemon and ½ orange

500ml water

250g sugar

½ cinnamon stick

1 vanilla pod

1 tablespoon of orange and lemon zest, grated.

Dark rum for drizzling

You will need 12 baba moulds, 40mm in diameter. Grease the moulds with softened butter. You will also need a mixer with a dough hook, as the dough is too soft to be handled, and a pastry bag with a plain nozzle for piping the dough into the moulds. Measure the flour, yeast, salt and sugar into the mixer bowl, then break in the eggs and start mixing at low speed. Once all the flour has been incorporated, increase the speed to medium.

Cut the butter, which should be at room temperature, into small pieces, and start adding it slowly to the dough, without stopping the mixer. Keep mixing until all the butter is well incorporated into the dough, which should be smooth and shiny. Stop the mixer and transfer the dough into a greased bowl. Cover with cling ?lm and let it rise in a warm place for about 1½ hours, or until doubled in size. In the meanwhile, butter the moulds and turn the oven to 165C. Gently deflate the dough with a spatula by folding it over itself several times, then transfer it into the pastry bag and pipe about 25g of the mixture into each mould, or about half full. Let the baba rise until they reach the rim of the moulds, about 25 minutes, then place them on an oven tray and bake for about 15 minutes, until golden. While the baba cool down, make the syrup, placing all the ingredients, except the rum, into a pan and letting them come to a boil. Let simmer for 15 minutes and then cool down. When the baba are cold, place them in a container that can be sealed and pour the syrup over them. Let them soak up the syrup for about 30minutes, turning the container every 10minutes or so, until they are soaked through. Take them out of the syrup and drizzle with rum to taste.

Spaghettini Sciuè Sciuè

In Neapolitan, sciuè sciuè means quickly, in a hurry. Fast food for Annunziata was having something ready when Carlo came home late from a visit to the cinema or taking a girl to a dance.

Serves 2

180g spaghettini

Sea salt

extra virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves

4-5 ripe plum tomatoes

Basil leaves

Add a large handful of spaghettinito a pot of boiling salted water. Stir to make sure they are well loosened in the water. In a wide frying pan warm 4-5tablespoons extra virgin olive oil and add the garlic cloves cut into slivers. Wash 4-5 very ripe plum tomatoes and, using your hands, squeeze them into the frying pan, discarding the skins and the seeds left in your hands. Cook on a brisk heat and season well with sea salt. Tear in plenty of fresh basil leaves and before the pasta is cooked use a fork or tongs to transfer the pasta dripping with the cooking water into the frying pan to ?nish cooking. Ready by the time Carlo has climbed up the 178 steps home. Sciuè, sciuè!

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here