THE slap of hooves on sun-dried earth. The creak and jingle of harness and harrower. A shallow cloud of dust rolling slowly across the field. This is arable farming as practised a century ago and now being demonstrated by Benny Duncan and his heavy horse, Geordie. Watching them is like peering back through time.

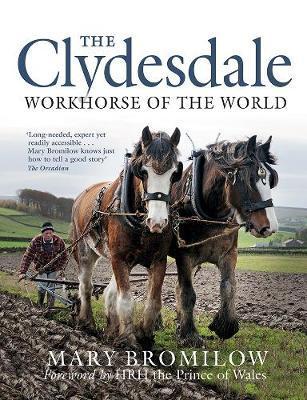

Duncan and his wife Isobel keep four working Clydesdales at their home here at Balmacolm near Cupar in Fife, and I've been invited along with author Mary Bromilow to watch them in action. Bromilow's 2011 book, The Clydesdale: Workhorse Of The World, has just been revised and re-released to cater for the resurgence of interest in a breed that until recently seemed bound for extinction.

“I think we came precious close to losing them,” Bromilow tells me as Duncan expertly steers Geordie back towards the stable yard. “But the way things are going now, they've had a stay of execution.”

By showing their horses at events like this weekend's Royal Highland Show, people like the Duncans are helping sustain the breed. “The more people who go and watch them at shows, the better.”

The logic of Bromilow's argument is that no-one who spends time in the company of these magnificent animals can fail to acknowledge the importance of keeping them in our lives. And after passing an afternoon with Jackson, Star, Davy and Geordie, I have to agree. With their huge frames, gentle natures, soft brown eyes and floppy forelocks, these horses really do, in Bromilow's words, “touch your love button” in a way that's hard to explain.

Reading Bromilow's book, a fascinating history of the breed which includes numerous interviews with Clydesdale aficionados, I was struck by the frequent use of words like nobility, dignity, bravery, courage, honesty and patience in describing these creatures. Does it make sense to credit them with what are essentially human virtues?

“Yes,” reply Duncan and Bromilow simultaneously. What's special about the Clydesdale, says Bromilow, is “the combination of strength and gentleness. They're big, they're strong, but there's no aggression in them. As an animal to work with as a partner, you couldn't pick anything better. They want to work with you. They want to please you. They learn quickly and they don't fight you, by and large.”

“Other horses have minds of their own,” says Duncan, who also keeps ponies. “You've two or three times the training to put into them.”

But can they really enjoy being yoked to heavy loads? “That horse there,” he says of Jackson, “is 18 hands high and weighs about a ton.” “If they didn't enjoy the work they wouldn't do it,” adds his wife – and Bromilow agrees. "Try forcing something that size and weight to do something it doesn't want to do," she laughs.

That steady, amiable temperament has been a hallmark since the early 19th century, when, writes Bromilow, “farmers in the area known as Clydesdale in Lanarkshire set out to breed the type of horse required for more productive farming and to meet the needs of Central Scotland's population growth and burgeoning industry”.

Selective husbandry and the inclusion of genes from a famous Flemish stallion created a sturdy, reliable and elegant horse, which by the end of the 19th century was in such demand at home and abroad that stud farms such as Andrew Montgomery's at Netherhall, Kirkcudbright, flourished. “At the height of the trade,” writes Bromilow, “special trains left Kirkcudbright Station early in the morning, loaded with Clydesdales to be shipped across the Atlantic from the Liverpool docks.” In 1911, some 1,617 stallions left the country.

Here in the UK, government grants placed stud fees within the means of small farmers and “stallion men” like Bromilow's grandfather travelled around the country with those powerful beasts, bedding down at farms where their charges were serving mares. For the owners, the business was lucrative: one legendary stallion, the 1908-born Baron's Footprint, earned £15,000 in stud fees over two seasons and was reputedly capable of serving one mare every two hours, night and day. When he died aged 22, he'd sired around 5000 foals.

For more than 100 years, the Clydesdale horse was a vital industrial force. Most farms kept one or more working “pairs” and at Balmacolm I meet 83-year-old Andrew Smith, who was brought up on the nearby farmstead. “My father was the gaffer,” he says. “There were three pairs and an orra horse, which did odd jobs. All Clydesdales. You had the gaffer, the foreman, the first horseman, second horseman and then the orra man. Each looked after his own pair and they took it week about to feed the horses at 5am before work started at 7am.”

From aged 10 or 11, Smith would drive the horses out to the fields and help with “ploughing, tottie drills, grubbing up, stacking and bringing in the sheaves. I loved it. I couldn't get home from school quick enough”.

By the time he left school aged 15 in the early 1950s, however, there was only one horse left, “Old Belle, a fine old Clydesdale”. Did he miss the others? “You didn't feel it much at the time because you were going into something new and interesting – the tractors. But it's a sad loss to see them go.”

The heavy horse's decline also left a void in cities. Older Glaswegians still talk fondly of the trace horses hauling loads up the West Nile Street hill to the goods station and at one time Glasgow Corporation's four-storey equine tenement block in Bell Street stabled 370 Clydesdales, which did myriad jobs including refuse collection. There's a lovely story in Bromilow's book about a carter struggling to put his horse's nose-bag on. "Hey, mister!” quipped a passing Clydesider. “You'll no' get that big horse intae that wee bag.”

The Falkirk-based soft drinks company AG Barr & Co ran a huge team of horses including the renowned Carnera, a 19.2hh Clydesdale who pulled cart-loads of crates around the streets until January 1937, when he broke his pelvis after slipping on the ice in Cow Wynd. For four hours, his driver and a local vet tried to raise him while weeping girls queued up to feed him buns and mattresses were brought from a nearby furniture store. The sympathetic crowd didn't disperse until, four hours later, Carnera's body was loaded onto a lorry and taken away.

Most poignantly of all, perhaps, a quarter-million British horses were lost on the Western Front during the First World War. Clydesdales were favoured for pulling heavy artillery guns and Bromilow writes movingly of their fate: “They died of disease and exhaustion. They were drowned in mud, gassed and blown to pieces.”

Of those that survived, only 62,000 came home. Some remained in Egypt, where many were maltreated on Cairo's streets; others were butchered for meat in Belgium and France. “It was,” writes Bromilow, “a terrible betrayal after their brave and willing service.”

By now, increasing automation was reducing demand for horses and although many saw service with the food-raising land armies during the Second World War, the decline continued after 1945 and some were shipped live to Antwerp for slaughter. In the 1970s, the Clydesdale was judged by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust to be vulnerable to extinction and by 2010, there were only 5000 left in the world, including just 800 in the UK.

What have we lost, now that those gentle giants have largely gone from our lives? “The relationship with his horse was a crucial part of a man's working life,” says Bromilow. “It was a hard working life but they loved their horses and took great care of them; some went in on their days off to clean the harness. When you take that away, the quality of your working life has gone. You can't build a relationship with a tractor.”

In a neat piece of historical reversal, Benny Duncan's agricultural career started with tractors and he didn't work with heavy horses until his early 40s. Born near the Fife village of Ceres, he began working on farms in the 1960s by which time the industry was already heavily mechanised.

He liked horses, though, and had just bought a pony when a friend who was dying of cancer asked if he'd like to buy his young Clydesdale. “I thought – what am I going to do with a Clydesdale? He pestered me for about a fortnight,” Duncan recalls fondly, “so eventually I said I'd buy it. That was a Sunday. My friend died on the Thursday.”

With the help of another friend, the well-known Clydesdale horse-breeder Ronnie Black, Duncan trained the youngster for driving and within a year he had bought a second horse to make a working pair.

Now 64, Duncan is “supposed to be retired” but he spends long days working with his four horses, which he shows at agricultural events and ploughing matches.

“I trained them all myself,” he tells me. “Star was three when I bought him. The others were nine months old and that's the best time to get them because you can get them into your way of thinking. A horse can sense if you are on the same wavelength.”

“Some people have that real gift of handling horses,” says Bromilow. “And some people, no matter how much they love them, haven't quite got it.”

It's obvious which camp Duncan falls into as he works quietly with Jackson and Davy, fastening the elaborate straps and buckles of their harness before hitching them to the beautiful replica wedding carriage which he drives to order.

“This is traditional old Scottish harness, bought second-hand,” he tells me. “You are talking £3000 for a set.” Keeping these huge animals isn't cheap. The feed bill is £100 per week and four lots of shoes come in at around £500 every five weeks – a sum Duncan doesn't object to, given the farrier's skill level. After all: “If you go into a garage, they charge so much an hour just to stand there playing on their phones.”

At last, the carriage is ready, Duncan is in his top hat and tails and Bromilow has taken her seat. And how thrilling it is to see Jackson and Davy trotting round a bend, blowing gently through their nostrils and lifting their feet proudly as they clop, clop, clop along the path.

As I watch, Duncan's granddaughter, Blythe Sinclair, drops in after school. Aged nine, she's already a skilful horsewoman who can drive, harrow and ride the 18-hand Star (with the help of a mounting ladder). She's also a highly articulate ambassador for horses as non-polluting alternatives to tractors.

Given the revival of interest in Clydesdales, could the horse be set for a comeback as a serious agricultural force? There have, after all, been earnest attempts to prove it's as economical as engine power and a few stalwarts – such as Sillywrea Farm in Northumberland and Craighead Farm in Ayrshire – continue to rely on horses. “They are certainly eco-friendly and there are things a horse can do that a tractor can't,” says Bromilow. “In forestry for example, a horse can get into parts of a wood that are inaccessible to tractors.”

However, the author – who grew up on a farm on Arran where her father was a shepherd – is pragmatic about the chances of a full-blown renaissance.

“You can't practically compare one of today's computerised tractors with a lone horse behind a plough. Given the expectation of productivity these days, it's hard to see how you could turn back to that.”

Then there is the human factor. “Farmworkers back in the day didn't really have holidays. You can't nowadays necessarily expect people to accept that way of life and you can't switch a horse off on a Friday night.”

But around the world, she says, “more and more people are finding new and different ways of using the Clydesdale's strength, agility and willing temperament”. Increasingly popular as a riding horse, the breed is the “backbone” of the Mounted Police Unit in Delaware, US, and Police Scotland have five pure-bred Clydesdales in their Ayrshire stable. Meanwhile, valuable promotional work is being done by the Clydesdale Horse Society and celebrity aficionados such as the actor Martin Clunes.

Equestrian competitions also raise the profile and according to Bromilow, Benny Duncan and his four working Clydesdales are “the ones to watch if you want to see not only how it is done, but how it should be done.”

A self-taught master horseman, Duncan does what he can to hand expertise to the next generation. (“There's an awful lot of knowledge in the cemetery,” he quips.) Meanwhile, rising talents like young Blythe Sinclair suggest the Clydesdale will continue to be championed for generations to come.

Let's hope so. In the city, and in the countryside, we need these animals in our lives. For while we may no longer depend on them to plough our fields and deliver our goods, we owe them a debt of gratitude for decades of service and companionship during some of the darkest chapters of our history. And how much poorer would our lives be if we lost the spirit of kindness and co-operation that, for centuries, linked human and working horse.

The Clydesdale: Workhorse Of The World by Mary Bromilow is published by Birlinn, £16.99. Benny and Isobel Duncan, along with Blythe Sinclair, are competing in various classes at The Royal Highland Show, which continues at Ingliston, Edinburgh this weekend (June 23 and 24)

The people's Clydesdales

The carters who worked with city horses did long days. “Mostly, they had to be at the stables by 6am in order to feed, water, muck out and groom their horses before harnessing them and yoking them to the lorries,” writes Bromilow. Later, back at the stables, “they had to do everything in reverse, taking off the harness, grooming and drying off their horses before feeding them and bedding them down for the night. Many of the horses were so accustomed to their routine that, after a drink in the yard trough, they made their own way up the ramp to the stables and into their own stall to be unharnessed”.

Glasgow's link with the Clydesdale horse continued long after its industrial heyday had passed. Although the cleansing department replaced its horses with lorries in 1956, the animals were used in parks maintenance until the late 1960s and reintroduced in June 1983 as part of the Glasgow's Miles Better Campaign. Since 1990 until recently, the four Clydesdales stabled at Pollok Park offered Christmas dray rides and competed at events such as the Royal Highland Show.

Two of those horses were the original models for Andy Scott's hugely popular Kelpies sculpture and while researching the first edition of her book, Mary Bromilow had the chance to be driven around Pollok Park by the Glasgow Clydesdales.

“I was struck by the smiles that cracked on people's faces the minute they saw the horses,” she recalls. “Not just children or older people, but everyone – people react very positively to them.”

For now, the Pollok Park stables are closed and the horses are not participating at this year's Royal Highland Show. Asked why, the council's press office offers this explanation: “Our Clydesdale horses are currently stabled outwith Glasgow due to a range of difficulties at our own stables in Pollok Country Park. A date for their return has still to be fixed but it is very much our aspiration to have them back in Glasgow as soon as possible.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel