People are always sending Paul Smith things. In the office where he sits, and from where he can see the opera house, London rooftops and planes stacking up above Heathrow, he is surrounded by stuff that has arrived by post or by hand or been picked up from somewhere or other. Look around.

There’s at least half a dozen bicycles for starters. He’s a huge cycling fan. Last year, he tells me, a woman brought him a bike all the way from Moscow on his birthday. Then there’s the cycling jerseys signed by his mates Sir Bradley Wiggins and Mark Cavendish.

But that’s just the start. There are books: Beano annuals (“1946 I can see in front of me,” he says), Boy’s Own annuals (“I just had Michael Palin here and he spotted the Boy’s Own. ‘Oh my dear boy. They’re marvellous.'”). There are toys, there are robots, there are hats and there are cameras. He’s a keen photographer. He even takes many of the photographs for his advertising campaigns himself.

So many things. “It’s pretty full,” Smith admits as he looks around. You wonder how many other giants of industry work in an office that resembles a dream version of a 1950s teenager’s bedroom.

Yet a giant he clearly is. He is his own boss, has no shareholders to answer to (though there have been 10 attempts to buy the company, he tells me), is friends with rock stars and his clothes are worn by Hollywood A-listers and the odd prime minister (Blair and Cameron). And if you ever get to see his passport you’ll see it bears the title Sir Paul Smith. Has done since the turn of the century.

Does anyone actually call him Sir Paul? “No, thank goodness.” You never do a Sir Ben Kingsley and demand it? “Absolutely not. I wasn’t even sure about accepting it when I got the letter from Buckingham Palace. I wasn’t really sure because it doesn’t really go with me. Then one of the girls in the office here said, ‘If your mum and dad were still alive they’d be ever so proud.’”

He thought about that and decided that, yes, he’d take it for his parents and his staff. “But I don’t even think it says ‘Sir’ on my credit card.”

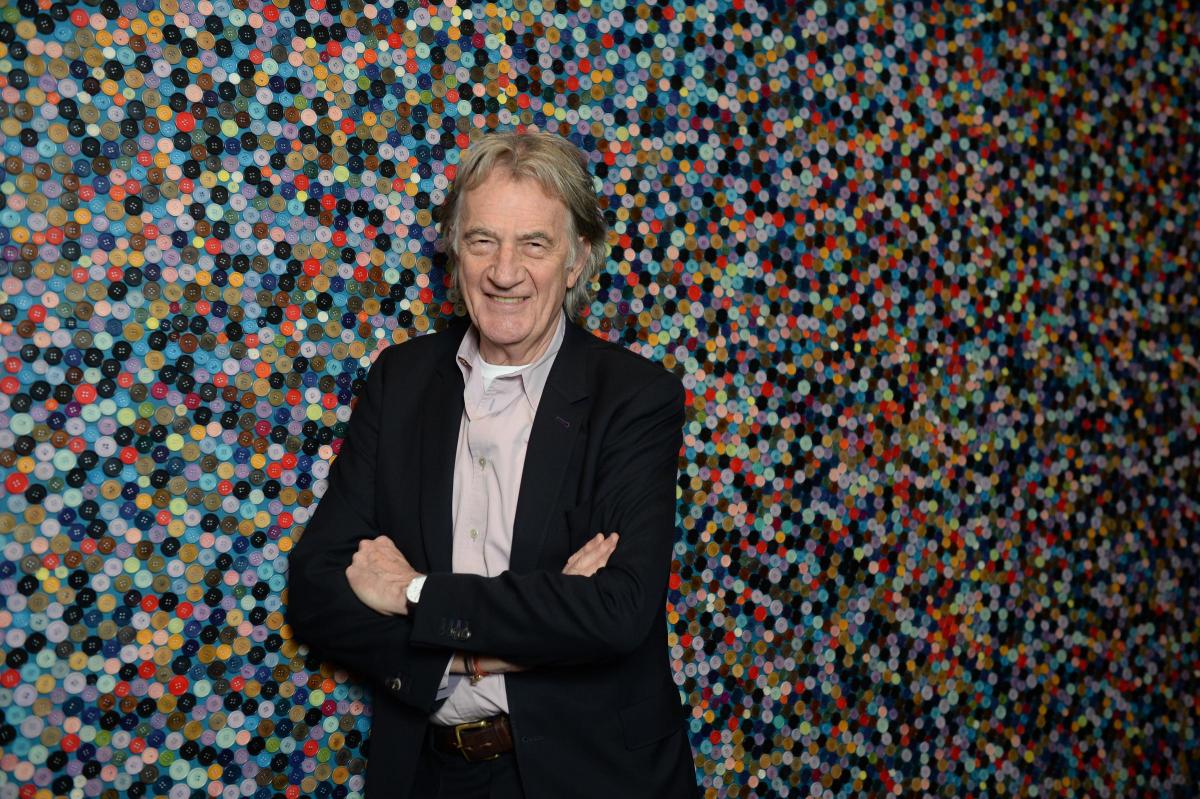

The passport gets plenty of use. Smith travels every Wednesday. This week he travelled to Glasgow. An exhibition, of which The Herald is media partner, on his life and career has opened at the Lighthouse, and he came to give it his blessing. And maybe, he admits, to look around for a building that might work as a Paul Smith shop. “We’ve been looking for years but I’m very funny about the shops. I like them ideally to be in an interesting building, to be not just a shop. Nobody needs another shop.”

There speaks a man who’s already got more than 130 of them around the world.

The exhibition, which has already been seen in London and Belgium, is a glimpse into his cluttered mind. He hopes it will show people he’s still down to earth (he says this a few times in our conversation; it clearly matters to him that we would think him so) and possibly inspire a few of its younger visitors. “I want to leave you with this feeling that you can do things that you might have thought you couldn’t,” he says.

“There’s a little bit of fashion in it but it’s really more about how I work. I hope young people will see I started in a very down-to-earth way and that you can progress, even starting in a way that is quite humble."

Well, indeed. That is the Paul Smith story. The shy working-class boy who made good, so good he is now worth, in conjunction with his wife Pauline, £290 million (according to the last Sunday Times Rich List), who sells clothes in 73 countries and who employs somewhere in the region of 1,000 staff, who started in 1970 in a hole-in-the-wall shop in Nottingham that was only open at weekends. (He spent the rest of the week working in the rag trade to earn a living.)

The exhibition includes a recreation of that shop, a little 12ft square box full of clothes Pauline had designed and things Smith had picked up from the local markets. “I’d have pen knives or posters or stamp albums, things that if you just walked in I could say, ‘Have you seen this? I’ve just found this in the market. Isn’t it interesting?’ It was a way of making people feel at ease. Because if you walked into that tiny shop you were literally right in front of me. It was very small.”

That magpie tendency can still be found in his office and his shops today. His modus operandi hasn’t changed, just the size and the number of stores. And the fact that he is the designer these days ever since Pauline stopped to study painting.

He does seem to live to work. It’s three in the afternoon when we speak and he’s already been in the office for nine hours (and he went for a swim at 5.15am before arriving at the office). He’ll not leave for another three hours.

He’s been doing this for nearly 55 years. Smith left school at 15 to work in the fashion industry. At the time he harboured a desire to be a professional cyclist. There were pictures of Jacques Anquetil on his wall which he’d taken from the French sports magazines he’d save his pocket money to buy. Was his teenage room as cluttered as his office? “No, because I had somebody called a mum.”

His love of the sport has continued to this day. Later this year he’s publishing the Paul Smith Cycling Scrapbook. One for the over-50s, he suspects. Did the fan in him get upset when the likes of Lance Armstrong were revealed to be drug cheats?

“I think the whole horror of all the cheating that’s going on …” he starts and then widens that horror out. “… And not just in cycling. You look at Fifa and corruption and the whole banking fraternity and the crash in 2008 … The world, unfortunately, has become a pretty naughty, bad place. Islamic State and wars and uprisings. It’s all part of this thing that human beings never seem to learn about, which is greed, ego, power, cheating. Nobody seems to learn from it."

He retreats to cycling again. “I am friends with Bradley Wiggins and Mark Cavendish who are clean-as-a-whistle cyclists and good guys and I know lots of fabulous actors and musicians through my job and they’re nice, normal people and there’s no cheating involved and no egos involved.”

Paul, are you seriously saying that there are no egos in the fashion business or the music business? “Oh, masses. I’m not saying there isn’t. I’m just saying I’m blessed with knowing lots of good guys.”

Smith’s cycling career ended before it began when, still a teenager, he cycled into the back of a car and broke his femur. Once he’d got out of his hospital bed he started going to the pub where he met a married woman with two children. She was called Pauline and was a lecturer and a design graduate of the Royal College of Art in London. She could see something in him.

Not his face perhaps. “Many years later,” he admits, "she said: ‘I didn’t fall in love with you because you were good-looking. I fell in love with you because you could make me laugh.’ She’s always kept my feet on the ground. I’m still the guy she met when I was 21.”

He enjoys talking about Pauline. He is openly, happily uxorious. It’s really rather lovely. “She’s very bright, she’s very well read,” he tells me. “She’s read Proust, Isaiah Berlin. She can paint and draw. She can sculpt. She’s ever so shy. Doesn’t like going out, not that social. It’s so opposite to me in many ways, which is probably why it’s worked so well.”

What do you argue about? “We haven’t ever had an argument and we’ve been together since 1967.” What, never? All married couples argue, don’t they? “Never, never, never, never,” he says. We’ll take that as never then.

“I won’t say we haven’t had a bit of a grumble but we’ve never had a proper argument." Then again, he says, “I’ve never had an argument at work. Very odd.”

Listening to Smith you can hear the post-war boy he once was. His vocabulary sometimes seems drawn from those old Boy’s Own annuals. And yet he was very much at home in post-1960s youth culture. By the start of the 1970s Smith was dressing bands such as Led Zeppelin and finding his feet in the male fashion world of the time, a time that, perhaps, saw the first real emergence of something we could label men’s style.

“In the 1960s – especially in London – the second or third generation after the horror of the war had the opportunity of actually expressing themselves in an honest way. And that came through the mod culture and the hippies and music. I was very close to that.”

The hippie style was, he now concedes, “quite silly”, but that wasn’t the point. “It was about self-expression. If you think about London in 1968 we were all dressing sillily with long hair. In France they were setting cars on fire in the 1968 riots. Our expression was more through how we looked.”

Of course the key to Smith’s business success was his ability to package a sense of rebellion into his clothes that could still be worn by those in more traditional professions (“classics with a twist” as the famous Paul Smith PR line always had it).

“If you went into any institution like banking or teaching or the BBC or newspapers just to wear a flowery tie or a colourful sock would have been considered absolutely outrageous [back then]. Even to give a thought to how you looked was considered very feminine and not the thing to do at all.

“I think where I managed to find a little space – it was never a calculated thing – was when I opened my first shop in London in 1979. I did suits that were slightly softer in construction and I would maybe do a Prince of Wales check [in the lining] that traditionally would have a burgundy overcheck. And I would put a lilac overcheck in or something.

“So it was a nudge. It wasn’t a shove. It was this little bit different and exciting. If you opened the jacket up and discovered there was a floral lining that was fantastic because from the outside your boss accepted it, but on the inside you knew you had your own little secret.”

Of course these days heads of banks and top politicians wear his suits. In his private heart of hearts is there anyone he’s seen in his clothes whom he wishes weren’t wearing them? I don’t say the name “Cameron” but I’m thinking it. Clearly he doesn’t have ESP because he doesn’t mention the PM.

“Over the years we’ve done some wacky things that you think, ‘I’m not sure about that on that person. On a rock star it looks absolutely fantastic but …’ I remember standing on Nottingham station considering pushing the man wearing a turquoise coat with dinosaurs printed on it from about 20 years before under the train. But I let him off.”

A womenswear line would eventually follow but only because the likes of Grace Coddington were dressing up models in Paul Smith clothes for photographers such as Bruce Weber and Patrick Demarchelier. He admits he struggled with the women’s line for a long time.

“The first two or three collections were really great because they were just men’s clothes that were made a bit smaller but then there was this whole bloody pressure from the press and buyers: ‘Oh, we need a skirt and we need a dress.' For eight or 10 years it was pretty tough for me because I don’t have a strong feminine side. When you design for women it’s obviously about the clothes but it’s also about the hair, the jewellery, the makeup, the bag and the clothes. And that took me a while to understand. But luckily I have a good team around me. A lot of women architects, interior designers, creative ladies like the clothes and they’ve still got that slightly androgynous look about them.”

One of the reasons he’s happy that he is still the boss of his company is the pressure he can see on other designers who haven’t got that luxury. He mentions Alexander McQueen’s suicide, and John Galliano’s drunken anti-Semitic comments.

“When you look at some of the tragedies – Alexander McQueen, John Galliano’s outburst because of too much pressure and then leaving Dior and now the new designer for Dior, Raf Simons, he’s just left because of the pace. And the designer for Lanvin’s left. A lot of the figures for the big brands around the world are seeing declines in business because of the oversupply of clothes.

“The big brands are in turn owned by merchant banks or hedge fund companies and they’re looking for a big return on their money or shareholders who are looking for more and more profits. I can completely understand why a lot of those designers are under enormous pressure.”

Because he owns the company he isn’t under that heavy weight. Still, time is moving on. Smith is 69 years old. “I’m not. You must have got that wrong, old boy,” he jokes.

I think you’ll find I’m right, Paul. “Gosh, am I? I never really think about age. I don’t do big birthday celebrations, not just because I’m embarrassed. I’m such a bore you know. I never argue. I am very laidback. I enjoy life. I’m sorry about that guys, but I just love every day. I’m not going anywhere unless I get to the point where I’m not quite with it. But I’m surrounded by a very young team and they give you great energy.”

Does he need it though? When I see him in Glasgow he's full of beans. In the five minutes before he goes live on STV he gives me a whistle-stop tour of the exhibition. We talk about the sites he's seen in Glasgow today (I'm not convinced he's convinced), we talk about the room full of things someone has sent him. Unwrapped things. Chairs covered in stamps and the like. And we talk about David Bowie. Because some of us have been talking about nothing else this month.

He shows me a picture he's just been sent. Taken from a photoshoot of Bowie. He blows it up on his phone and in the corner, peering through a gap in the backdrop is Paul Smith. Not quite at the centre but near enough. Maybe, I think, you could read a life – his life – into that image. He goes to talk to the camera. Back to work.

Hello My Name is Paul Smith continues at the Lighthouse, Glasgow until March 20. Tickets £6 for adults, £4 concessions.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here