After last year’s marathon entry we’re going to keep things tight this week because we’re going off on holiday (drop back in next week for an interview with Joe Sacco from the archive).

So while we pack a couple of new graphic novels in the suitcase we thought we’d just update you on Graphic Content’s recent reading. It may give you some ideas.

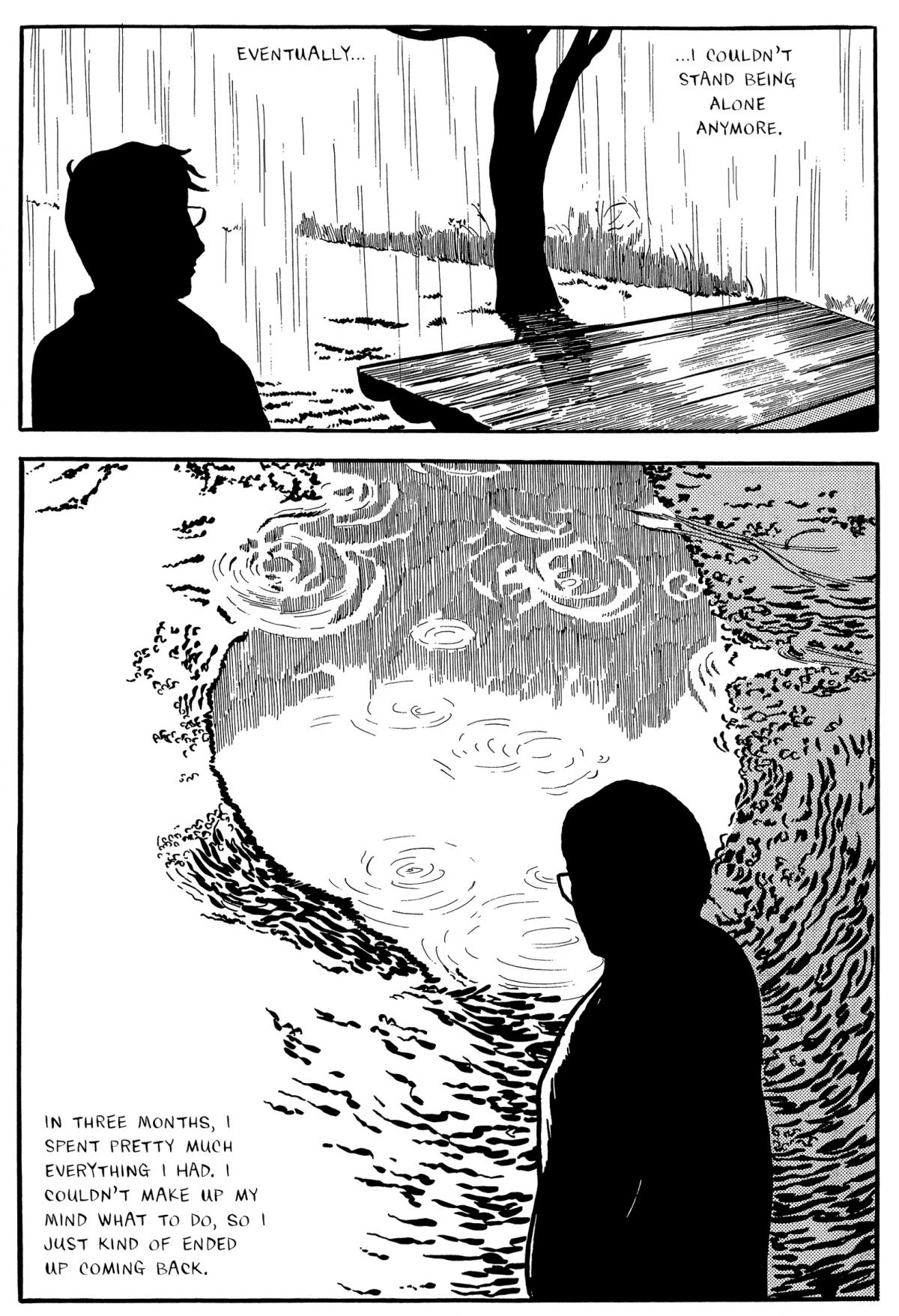

Trash Market by Tadao Tsuge

Occasionally we nominate a Graphic Novel of the Month in this blog. Not every month because sometimes it doesn’t seem merited, and sometimes we have other fish to fry. If we had nothing else on our mind this week then Trash Market might well be this month’s nomination.A collection of strips from the late 1960s and early seventies by the alternative manga creator Tadao Tsuge, they are full of poverty, violence (some of it sexual), riots and despair, sketched out in crude, stiff, ugly shapes. The result is often remarkable.

It also offers us a vision of lives laid low in modern Japan. The title story concerns a group of men waiting around to sell their blood. And as Ryan Holberg points out in an accompanying essay, that story is about as happy as this book gets.

But there’s a power to these stories that grow in part from the fact that Tsuge knows the world of which he writes and draws (he worked for years cleaning in Tokyo’s for-profit blood banks) and partly because for all their crudity there is a potency to his imagery, whether it’s in the absurdist cartoonishness of the violence or the careworn ordinariness of his character’s faces.

His stories have a doomy weight to them but at times meander into unusual places. They do what the best stories do. They make you see the world in a way that you never have before.

Grip: The Strange World of Men

Look,I can’t pretend I really know what’s going on here. This compilation of Hernandez’s turn-of-the-century DC comic is weird and wild with a cherry on top. It’s about – I think – a cult leader, strange powers, Hernandez’s breast fetish, ultraviolence, pulp thrills and some of the most disturbing imagery outwith a Charles Burns comic. The character Mr Skin is comic book Lynchian. And maybe that’s underselling it.

I’m not sure it adds up to very much of anything but it has an icky,messy compulsion to it that keeps you turning the pages.

If you were reading the Sunday Herald a couple of weeks ago you would have hopefully noticed our interview with Eddie Campbell.The accompanying Graphic Novel round-up didn’t go online so we’re rectifying that here:

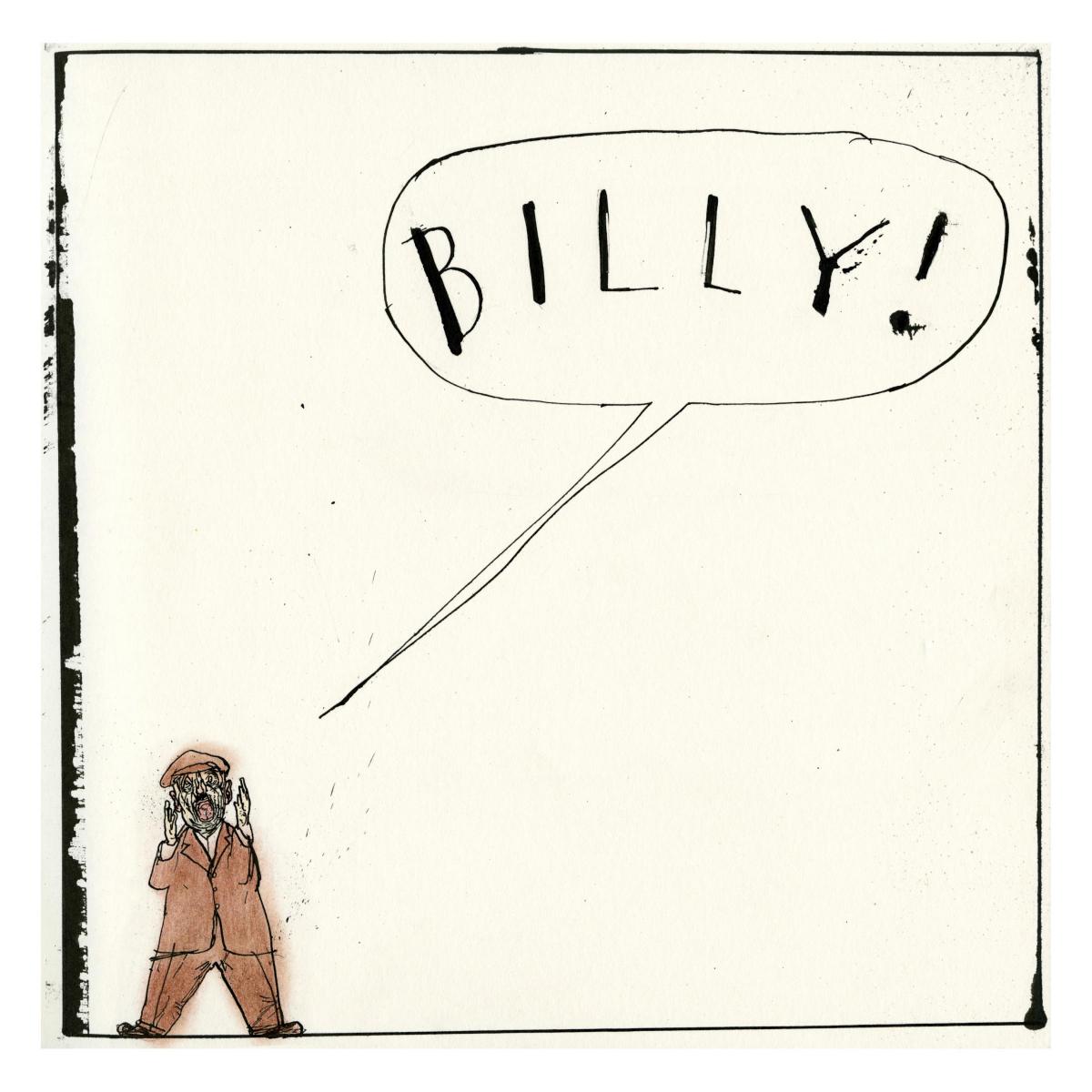

The Pillbox, David Hughes

Golemchik, William Exley

Never Goodnight, Coco Moodyson

Orson Welles did not have a high opinion of his fellow film director Michelangelo Antonioni. “He gives you a full shot of somebody walking down a road,” Welles once said of the Italian film-maker. “And you think, 'Well, he's not going to carry that woman all the way up that road.' But he does. And then she leaves and you go on looking at the road after she's gone."

I thought of that quote reading David Hughes’s new graphic novel The Pillbox (Jonathan Cape, £18.99). About 40 pages in, there’s the comic-book equivalent of an Antonioni long take. Six double-page spreads of a beach scene which shows a couple walking across said beach from before they start to the moment they are in medium close-up.

It’s not an exact comparison. Unless you are watching the Antonioni film on a small screen with a fast-forward facility you can’t skip frames. The reader has more agency than a viewer. So it is up to the cartoonist to try to pace the reader through the story.

So it should be said one of the many pleasures of The Pillbox is that formal one; the manner in which Hughes speeds things up and slows things down, takes control of how you navigate its pages.

An illustrator by trade, Hughes has an inclination towards a scratchy minimalism not a million miles away from Eddie Campbell, but his lines thicken and thin at will, images densify and then clear, circle around and then nest inside other imagery. Grid panels give way to full pages and spreads. Imagery repeats and repeats then breaks away. All in all, it is a masterclass in pacing.

What’s it about, you ask? Ah well. It’s a cool, even chilly take, on the English seaside, ghosts and abuse. Not particularly cheery to be honest. Although there are woolly mammoths too.

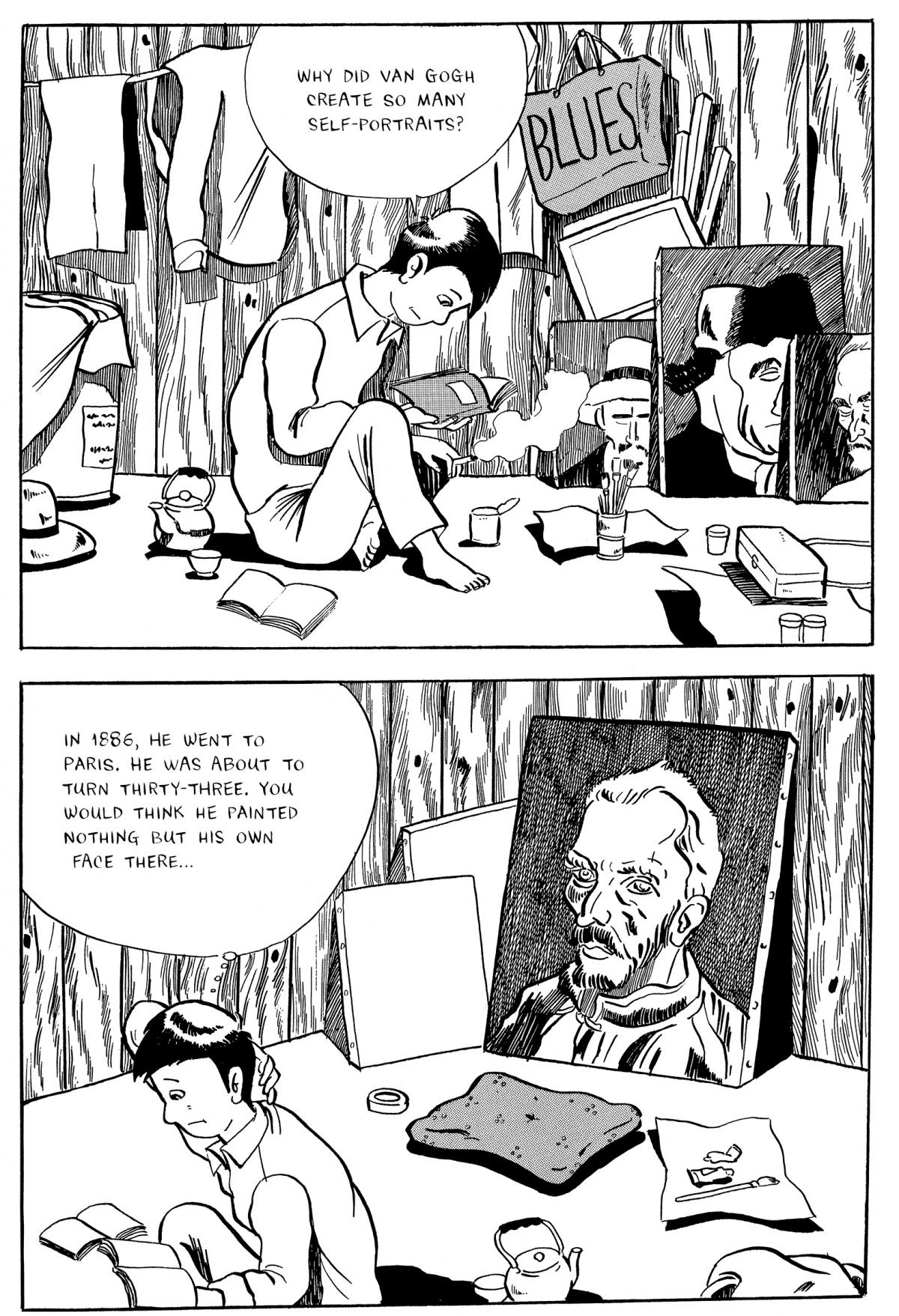

It makes for an interesting comparison with newcomer William Exley’s Golemchik (Nobrow, £6.50), the latest in the publisher’s 17x23 series designed to promote new cartoonists.

If you can see Hughes as a successor to the likes of Gerald Scarfe and Ralph Steadman, Exley’s work is much softer, warmer and sweeter. And more modest. Golemchik takes the format of a comic strip but the tone of a children’s book, telling as it does the story of a young boy’s search for a friend. He finds one in a pile of rocks that becomes animated and goes around clumsily breaking things. The damage here is material rather than emotional.

Exley is confined by limitations of space (Golemchik is less than 25 pages long) and there is a sense of rush and hurry about the whole thing. And at times the tone lurches from as if Exley is being controlled by the story rather than the other way around. But as a calling card this is hugely promising. Visually, it’s also rather lovely.

The same could be said of Sam Bosma’s Fantasy Sports No. 1 (Nobrow, £12.95), a manga-flavoured fantasy containing a baseball-playing Mummy, skeletons and a young wizard, that also benefits from Nobrow’s typical high production values.

But for something that has as much bite and weight as The Pillbox there’s Coco Moodysson’s Never Goodnight (The Friday Project, £14.99), the graphic novel that was adapted into the film We Are the Best, directed by Moodysson’s husband Lukas.

Moodysson’s art here is crude and clunky but it fits the narrative she wants to tell. Set in 1982, it’s the story of a trio of girls who form a punk band (even though they don’t have any instruments) in a bid to take control of their lives. It’s a story that’s both sweet and spiky -– maybe a mix of mohican and mohair – told in short, sharp vignettes that sketch out teenage frustrations. “Your parents may be more annoying than ours ...” one of the girls says to her friend at one point. “That’s what I keep telling you,” the friend says. “I win.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here