When France fell in six short weeks in the summer of 1940, just 10 per cent of its land mass was under Nazi control. French soldiers and their allies had neither been outnumbered nor – radios aside – ill-equipped. They had not fought badly. Yet by the time an armistice was imposed on 22 June, 2.29 million of those who had confronted Hitler were dead, wounded, or prisoners. Of the POWs, 1.8 million were Frenchmen.

It is hard to explain now; at the time, it was impossible to comprehend. Britain turned the Dunkirk evacuation into a kind of victory-in-defeat, determined to obscure the facts of a debacle. France had no such consolations. The “impregnable” Maginot fortifications had proved as useless as French generals. A government that had promised to stand firm had found “compelling military reasons” to take to its heels. And Paris had been declared an open city, prey to be claimed.

That summer saw one of the most haunting events in French (or any other) history. Readers of Irene Nemirovsky’s Suite Francaise, or Leon Werth’s recently-rediscovered 33 Days, will have a sense of it. The government’s sudden departure was interpreted by Parisians, as David Drake writes, “as confirmation that Paris was in danger of becoming a war zone and of falling into German hands”. So began “the exodus”, a human deluge flooding the roads as three million people fled the city.

It was a mad, dangerous, and ultimately pointless affair. When the first Germans trundled into Paris on 14 June “they felt as if they were entering a ghost town”. Yet even as they dashed or stumbled southwards, most of the three million citizens knew that escape was an illusion. Those who had fled in panic soon returned in a haze of shock, shame and anger to attempt to understand what occupation meant.

Other cities, great cities, had fallen to the Nazis. Some had been pulverised in the process. But this was Paris, then as now prone to regard itself as the heart of European civilisation. As the evil Major Strasser would ask of our hero, Rick, in the 1942 movie Casablanca: “Are you one of those people who cannot imagine the Germans in their beloved Paris?”

Many would have not have hesitated over an answer. The cultural pre-eminence of Paris had been an established fact for long enough. France’s intense, haughty pride in the City of Light, with all its affectations, its snobbery and its bloody history, matched the singular fact. If Paris was conquered, if Paris was at risk, Europe and its civilisation were conquered and at risk. In the summer of 1940, unthinkably, the barbarians were inside the gates.

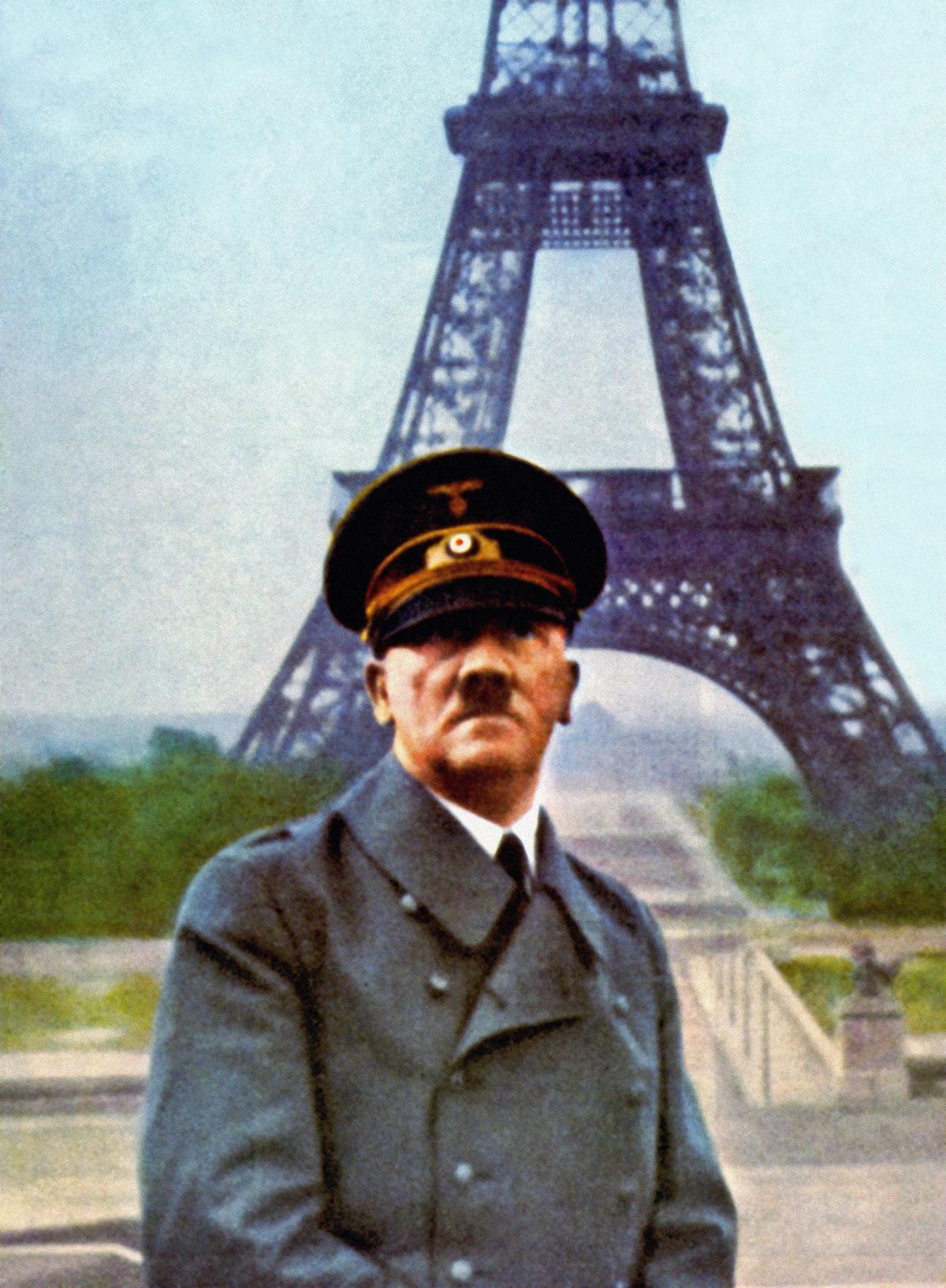

These notions were taken seriously. Given the reality of Hitler’s regime, we might hesitate before doubting them. Yet one striking thing about Drake’s marvellous history is the extent to which the Nazis, too, venerated Paris. Their devotion was shot through with resentment and envy, but their Fuhrer was quick to award himself a tour of the city’s landmarks. When they were not brutalising and robbing the citizenry, his underlings – under strict instructions to behave decorously – couldn’t get enough of Paris.

The citizens, deliberately avoiding eye contact, would refer with patronising irony to ces messieurs (“these gentlemen”). Paris might fear and despise the Nazis. It might have been humiliated by them. Realistically, it might have few weapons with which to oppose them until the Resistance rose in the days of the Liberation. But Paris would never be impressed by les Boches. The Nazis, as though proving a point, hated “this pejorative term”.

For the most part, Drake allows innumerable facts to speak for themselves. Implicit in his study, nevertheless, there is a question: why Paris? Why did its fate seem to matter so much in 1940, to victors and vanquished alike, when most of the continent was subjugated? Why is there these days a large, growing body of literature by non-French writers devoted to the war-time tribulations of the French and their capital? Perhaps those assumptions about Europe, civilisation and barbarism are not so quaint after all.

Part of the fascination has something to do with the fact that Britain and the United States did not endure occupation. In parallel is the complicated truth of the French experience. Countries spared the test wonder how their societies might have coped; France still struggles to come to terms with what happened. British chauvinists seize on “the myth of resistance” - a fatuous misrepresentation – as though to assert, nonsensically, that “we” would not have been craven. Yet we wonder.

What animates curiosity is the suspicion that if Paris could fall so easily Europe’s vaunted civilisation must have had a weak heart to begin with. Pre-war France certainly incubated plenty of fascists of its own. Communists, equally, were significant actors in the city’s dramas. Democracy, as embodied by the Third Republic, had for much of the time been an unstable, crisis-ridden farce before the fall.

Ordinary Parisians were meanwhile as varied as humanity. Generally they were the most perplexing breed of all: they were ordinary. Drake has relied heavily on their diaries and memories, a technique that other historians of the period have questioned, but one that is here fully justified. Common folk have few motives for deceit. Besides, Drake also makes use of newspapers, police records, film and radio while remaining perfectly aware of their provenances. As a mosaic, it works wonderfully well.

So we hear of writers and resistants, schoolgirls and police, teachers and thugs. There is the appalling Bonny-Lafont gang of sadistic criminals growing rich on an alliance with the Gestapo. There are publishers falling over themselves to ban books while a few souls risk all to disseminate words of inspiration. There are convinced fascists, mere opportunists, and people who took to resistance almost as a means to stay sane. A handful of rich parasites prosper; ordinary Parisians go hungry, freeze, and struggle against loneliness and fear with no way of knowing when, or if, the nightmare will end.

Jews were banned, robbed, blamed for food shortages, blamed for the war itself. Official Paris, in Vichy’s name, did more than it was bid by the Nazis in the rafles (round-ups), most infamously during la Rafle du Vel’d’Hiv in the summer of 1941, when 8,160 parents and children were despatched to the camps from a hell-hole in the Velodrome d’Hiver indoor stadium, a hell-hole run by the French. Yet as the irritated Nazis discovered when the numbers deported fell short of their targets, “Jews were being hidden and protected by non-Jews”.

As the author puts it in his concluding pages, French revisionist histories have in recent decades substituted one generalisation for another, “opening up a new era during which the myth that ‘everyone resisted’ was replaced by the fiction that ‘everyone collaborated’.” That kind of fiction masquerading as truth, absolutist and implacable, is dangerous.

Instead, Drake’s book contains two “tiny” minorities: those committed to resistance and those committed to collaboration. Alongside those groups there was a majority “focused on doing their best to survive increasing hardship and deprivation while making as few compromises as they could”. In their lives, perhaps, there was a larger human truth.

Paris At War: 1939-1944, by David Drake (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, £25)

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here