THEY were hidden away from Scottish society with diagnoses such as melancholia, imbecility and a weak mind.

But now the lives of patients who spent years, in some cases decades, in a Victorian asylum have been made widely accessible to the public.

The letters, photographs and case histories of patients who were confined to Stirling District Asylum have been conserved and catalogued by archivists at Stirling University over the last three years.

Within the 50 volumes, passed to the university by the NHS, are tales of ordinary people who - affected by mental illness and other health problems - led extraordinary lives.

Among them a farmer, James Dempster, who had spent some time in the United States and was admitted in 1881 with a “supposed cause of insanity” of “sunstroke".

His uncle reported that while staying at the family home in Clackmannan he had threatened both his sister and a servant. While the staff found him to be "very quiet and no trouble", the records show he was upset by the possibility of horses crushing fairies in the hospital garden. A note from September 1709 says he “takes a great interest in the small stream beyond the house and says that fairy children play there and gets wildly excited if a horse is driven through the stream as it may kill his fairy children."

Karl Magee, archivist at Stirling University, said: "Every individual story is different and every individual story is interesting in its own right. The case books contain notes from thousands of patients but it is very easy to get caught up in stories of each individual."

Opening in 1869 Stirling District Asylum had admitted more than 9000 people by 1918, many of them paupers.

From 1890, Mr Magee said staff began photographing patients - something which makes the archive particularly attractive.

"People doing family history research may never have seen a photo of their family member before," he said. "The vast majority of patients were classed as paupers so they were quite poor and in need of assistance, so they would not have had access to cameras."

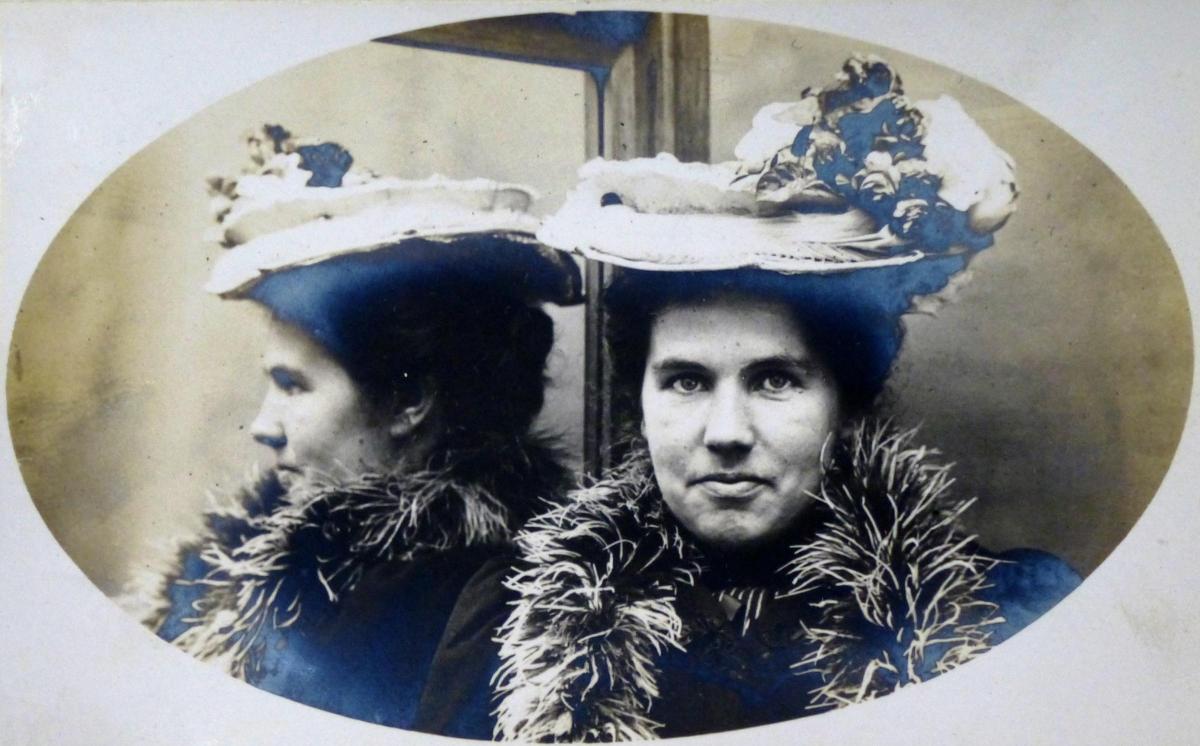

Standing-out is a striking dark-haired lady, wearing a white hat adorned with flowers and a fine feather boa. She is Susannah Robb, a married housewife from Bathgate, who was admitted as one of the few private patients in 1908 with a form of "delirious insanity” caused by an infection post childbirth. Standing by a mirror, with lips that seem to suppress a grin, it is hard to believe she was found away from her home with no idea where she was or how she got there. She left the asylum in August 1908 against medical advice but returned the following January apparently unable to cope.

Other patients appear luckier - at least when it came to rejoining the community. Archibald Norval was admitted in 1892 at the tender age of 28 diagnosed with "the insanity of epilepsy". He suffered a seizure playing football in the hospital grounds that autumn and subsequently endured a trepanning operation where the skull is drilled to relieve pressure on the brain – a common technique at the time. He was discharged the following year and in 1894 wrote cheerily saying he was working 14 to 15 hours a day as an engineer.

Others such as Hugh Flemming, a clerk admitted aged 34, lived in the asylum until their death. Mr Flemming's own father had been a patient at the same institution and he arrived believing his wife was trying to poison him. A love poem he wrote in 1895 suggests he dreamed of happier times: "A visit to sweet Campsie Glen/ I sincerely fondly wish/ For there in youths bright happy days/ I used to go to fish."

Mr Magee said releasing the archives, previously held by NHS Forth Valley, filled a gap in central Scotland as records for Glasgow and Edinburgh asylums were already available.

Family historians and those researching medicine, nursing and the Victorian language are among those who have already looked through the pages. The records are accessible at Stirling University library. Artwork produced by artist Sharon Quigley with patients and staff at the now-named Bellsdyke Hospital in response to the archives will be on display at the University’s Pathfoot Building from January 23 to May 27.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel