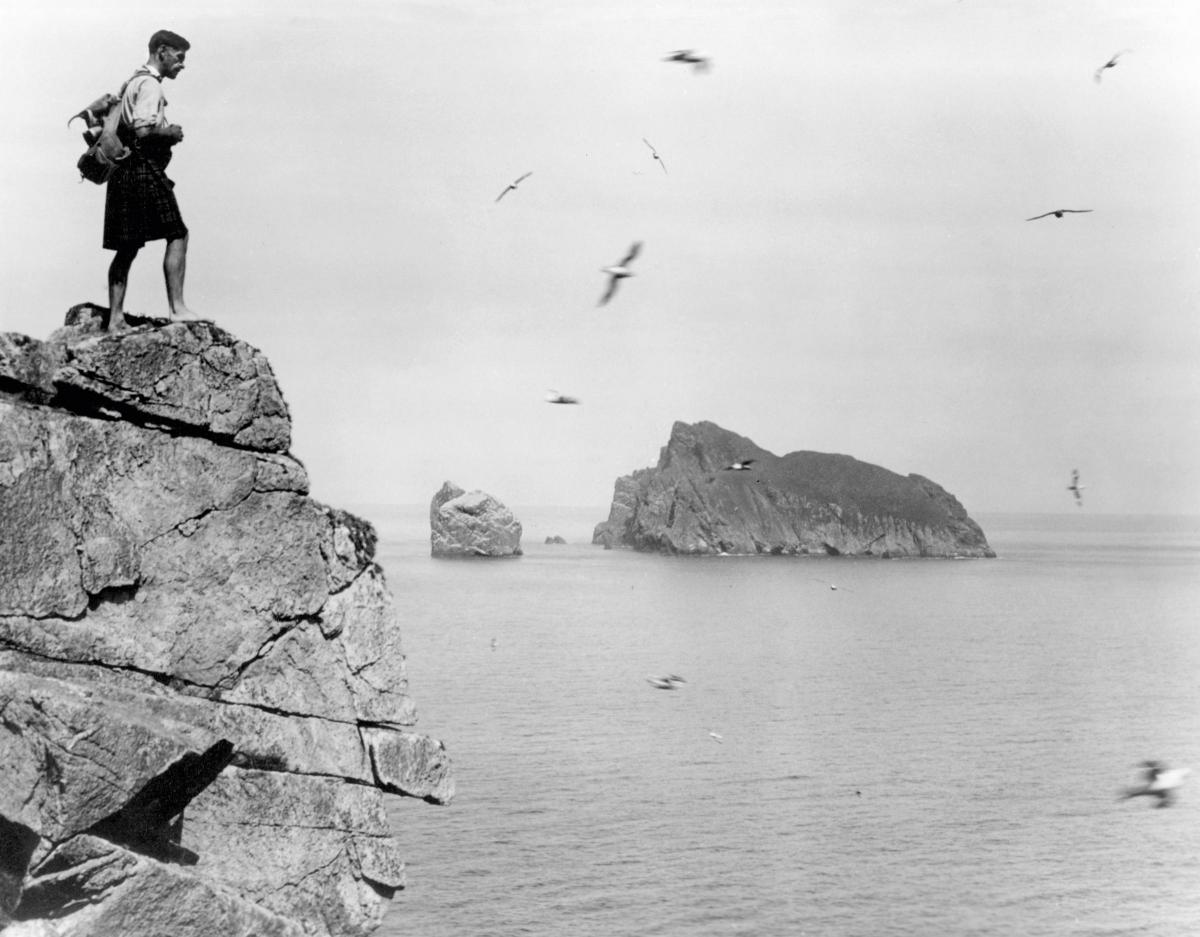

IN the summer of 1758, just 12 years after three Royal Navy warships had visited St Kilda in search of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Reverend Kenneth Macaulay became one of the archipelago's first tourists during an official visit. He recalled standing petrified as the St Kildans

demonstrated their prowess on the crags:

"Two noted heroes were drawn out from among the ablest men of the community: One of them fixed himself on a craggy shelf: His companion went down 60 fathoms [110m] below him; and after having darted himself away from the face of a most alarming precipice, hanging over the ocean, he began to play his gambols: he sung merrily, and laughed very heartily. The crew were inexpressibly happy, but for my part, I was all the while in such distress of mind, that I could not for my life run over half the scene with my eyes."

This is the earliest description of a St Kildan deliberately trying to impress a visitor with a display of their climbing skills: it was a performance that would be witnessed by many over the next 180 years. Macaulay and his fellow adventurers portrayed a visit to the islands as an experience of high drama and romance. In the aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellion, the political temperature of the Highlands and Islands cooled, opening up the opportunity for what Elizabeth Bray has called the "discovery of the Hebrides".

Visits to St Kilda for the most intrepid became more common from about 1800, but notable early travellers, including Thomas Pennant

and Samuel Johnson, never reached St Kilda, and we often need to turn

instead to accounts produced by lesser known writers.

In 1831, George Atkinson set a precedent when he chartered a boat

specifically for the trip. Just three years later, the Glenalbyn became the

first steamship to reach Village Bay, causing "excitement and astonishment" among the islanders. The reaction of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland that same summer is recorded in his journals and letters, which betray both a recognition of the St Kildans' abilities – one islander was noted as "rather intelligent' – and a pressing need to judge them. Tourism, even at this early date, was mixed up with morality and philanthropy.

The sharp-witted St Kildans seized the opportunity to capitalise upon

the chance to sell souvenirs such as cheese, brooches and even apparently dogs. At the same time, Acland provided the St Kildans with 20 sovereigns "to help them build new houses". The impact and intervention of tourists could be both dramatic and well-intentioned, in this case providing the catalyst that brought about the wholesale redevelopment of Hirta's housing and farmland in Village Bay.

The first visit by a scheduled commercial vessel came in 1877. The

steamer Dunara Castle arrived from Glasgow, carrying about 40 passengers on a tour of the west coast that included Skye and Harris. At this time the St Kildans themselves, as well as the romantic landscape, were the subject of a pervasive and perverse interest. Their community was cast as an example of an evolutionary backwater – a survival of "the past in the present". For their part, the islanders looked forward to more prosaic advantages, such as regular post and communication.

The Dunara Castle and other steamers continued to ply the route to St

Kilda until the outbreak of the Second World War. Some of the best-known memoirs of the islands come from this time, such as Richard Kearton's With Nature And A Camera, and Norman Heathcote's St Kilda. As in the years before the war, after 1919 the steamers not only brought an influx of visitors, but also the opportunity to import foodstuffs, as well as export the islanders' own produce.

Some of the most evocative material comes from a small collection of

films held at the Scottish Screen Archive. Footage dating to around 1929 captures a voyage by the Hebrides and features rare demonstrations by the islanders of spinning wool and abseiling on the cliffs for birds.13 After the evacuation of 1930, the steamers continued to visit during the summer, although now their only purpose was to bring the tourists, including some St Kildans, to the islands. Colour film of a trip in the 1930s shows the Dunara Castle in Village Bay more than 50 years after her first visit, with smoke rising from the chimneys at No. 11.

A major hiatus occurred after 1939 when, for the first time in over 60

years, there were no regular trips to St Kilda. The era of modern tourism

began about 20 years later, with the first visits of the NTS cruise ship

SS Meteor. Short trips, although not a new invention, are now far more

commonplace, with as many as five boats coming to the island on any one day. Some 5,000 visitors can now reach the islands each summer.

The effect of tourism on the archaeology of the island is important in two respects. Before the re-occupation in 1957, the practice of archaeology on the island was sporadic and piecemeal, being often undertaken by tourists and "sightseers". In this context, it is perhaps less of a surprise that a visitor like Captain Patrick Grant of the Indian Army, should have been asked to report on the souterrain for RCAHMS (The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland) in 1924.

Early excavators like the ecclesiologist Thomas Muir were only on the island for a short time, while later archaeological studies, such as those of John Mathieson, were represented as a secondary concern. The second effect of tourism has been on the landscape. While crofts were established over much of north-west Scotland by estates and their factors, the catalyst on St Kilda came from Acland, a tourist. Furthermore, the advent of work parties on St Kilda from 1958 has itself created a continuing link between tourism and the active management of St Kilda's landscape – the sites within Village Bay now being kept in a state of arrested decay.

Looking back to the beginnings of tourism, the old steamships that once

provided such a crucial link for the islands also offered trading opportunities and connections. The very existence of the community became enmeshed with seasonal visitors and, even now, their demands continue to have a great impact on both the modern and historical fabric of the islands. On today's St Kilda, it is seldom clear where tourism begins and ends, and which of us is a visitor.

Extracted from St Kilda: The Last And Outmost Isle by Angela Gannon and George Geddes, published by the Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland.

George Geddes will be talking about the book at the Aye Write! festival on March 19, 1.30-2.30pm, the Mitchell Library. The Sunday Herald is the festival's media partner. For programme information and tickets visit www.ayewrite.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here