She is one of the world's photographic pioneers, a hitherto obscure Scottish woman who helped create some of the earliest photographic masterpieces.

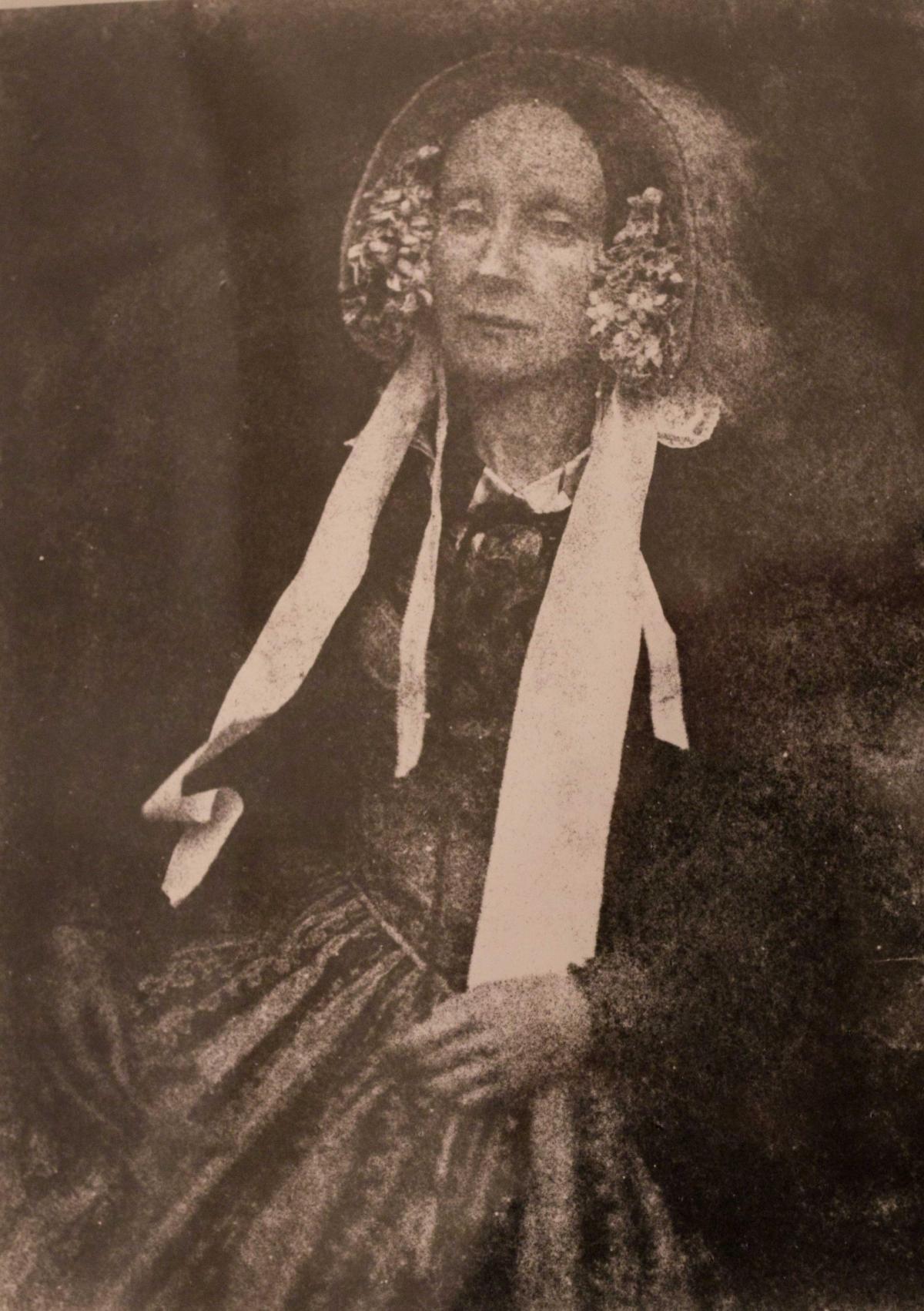

Now a mysterious photographic portrait of a Scottish lady in a bonnet, sitting with blackened hand, has been identified as Jessie Mann, a Perthshire woman who lived in Edinburgh in the 1840s and was a key associate to the ground-breaking Scottish photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson.

The discovery comes as Ms Mann, and her crucial role in the development of early photography, is to be recognised officially for the first time in a major exhibition.

Jessie Mann, and what is now firmly believed to be an image of her and her sister, is to be highlighted in the major Painting With Light exhibition, which opens at Tate Britain on May 11.

The exhibition comes as a portrait has been discovered which is likely the only surviving full image of the enigmatic Ms Mann.

Roddy Simpson, a leading photohistorian and honorary research fellow at the University of Glasgow has identified the picture, a portrait of an Unknown Woman, as her.

The image, Unknown Woman 15 in the National Galleries of Scotland archives, shows the woman in a bonnet with a discoloured hand - Ms Mann is likely to have stained her hand using a chemical, silver nitrate, required at the time for the photographic process.

Silver nitrate blackens skin, and the calotype technique used by Hill, Adamson and Mann uses paper coated with silver.

Although her precise involvement in the complex and artistic calotype photography of Hill and Adamson is unknown, a letter from the painter James Naysmith to Hill, written in 1845, asks about the health of Miss Mann, “that most skillful and zealous of assistants”.

The Tate's show, curated by Carol Jacobi, curator of British Art, features an image of Two Women in Bonnets, taken in the 1840s.

One of these women is now firmly identified as Jessie Mann, and was the basis for an image of her in a major painting of the Free Church's Disruption of 1843, painted by Hill.

Ms Jacobi said: "This is a very good opportunity to bring her into better view - she was present right at the start of modern photography and was a clearly a key figure in their work."

The Disruption painting, a large work painted by Hill over 20 years with its portraits based on photographs, is also in the show.

Mr Simpson, who has unearthed many of the scant details of her life, said of the new image: "The bonnet, the high brow, she really could be Jessie Mann - early photography was a dark art and her hands were likely stained by silver nitrate."

He added: "It was general knowledge in Edinburgh at the time that she was working with Hill and Adamson on their photography.

"There are no official images of her, but this could be her. Naysmith wrote about her, and what she contributed to their work is open to speculation.

"She probably did a lot of printing and processing. She was obviously quite sophisticated and educated - she was definitely an associate, not a servant.

"This exhibition is exciting because she is being acknowledged for the first time, one of the first women to be involved in photography, Hill and Adamson revolutionised it and she was a key contributor."

Hill and Adamson created thousands of calotype portraits, views and landscapes, and have been acknowledged as the forefathers of modern photography. More than 5000 of their images are held by the National Galleries of Scotland.

Hill, a painter and member of the artistic establishment, teamed up with Adamson, a master of early photographic techniques.

They hired Miss Mann to help them capture the likenesses of the 450 ministers who had seceded from the Church of Scotland in the Great Disruption to form the Free Church of Scotland.

Mr Simpson also found the image, Two Women in Bonnets, in the Special Collections Department at the University of Glasgow.

Two other British women involved in photography in the 1840s were Anna Atkins and Constance Talbot.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here