Macaroni, figs, fruit and porridge: the everyday life and diet of the 60 Roman soldiers who manned a major fort on the outskirts of Glasgow has been revealed.

The Roman soldiers posted to the fort in Bearsden nearly 2000 years ago, an outpost of the Antonine Wall, valued food that reminded them of home as they patrolled the northernmost frontier of their Empire, a summation of years of excavations and analysis of the ruins has found.

The 60 to 100 soldiers based in Bearsden ate macaroni pasta, made from durum wheat, had porridge and fruit for breakfast and ate imported figs, coriander and wheat from France and southern Spain, a new book, Bearsden: A Roman Fort on the Antonine Wall, reveals.

The soldiers, perhaps homesick but also taking advantage of a European trade network under the Roman Empire, ate food imported from Gaul (France), England and Spain.

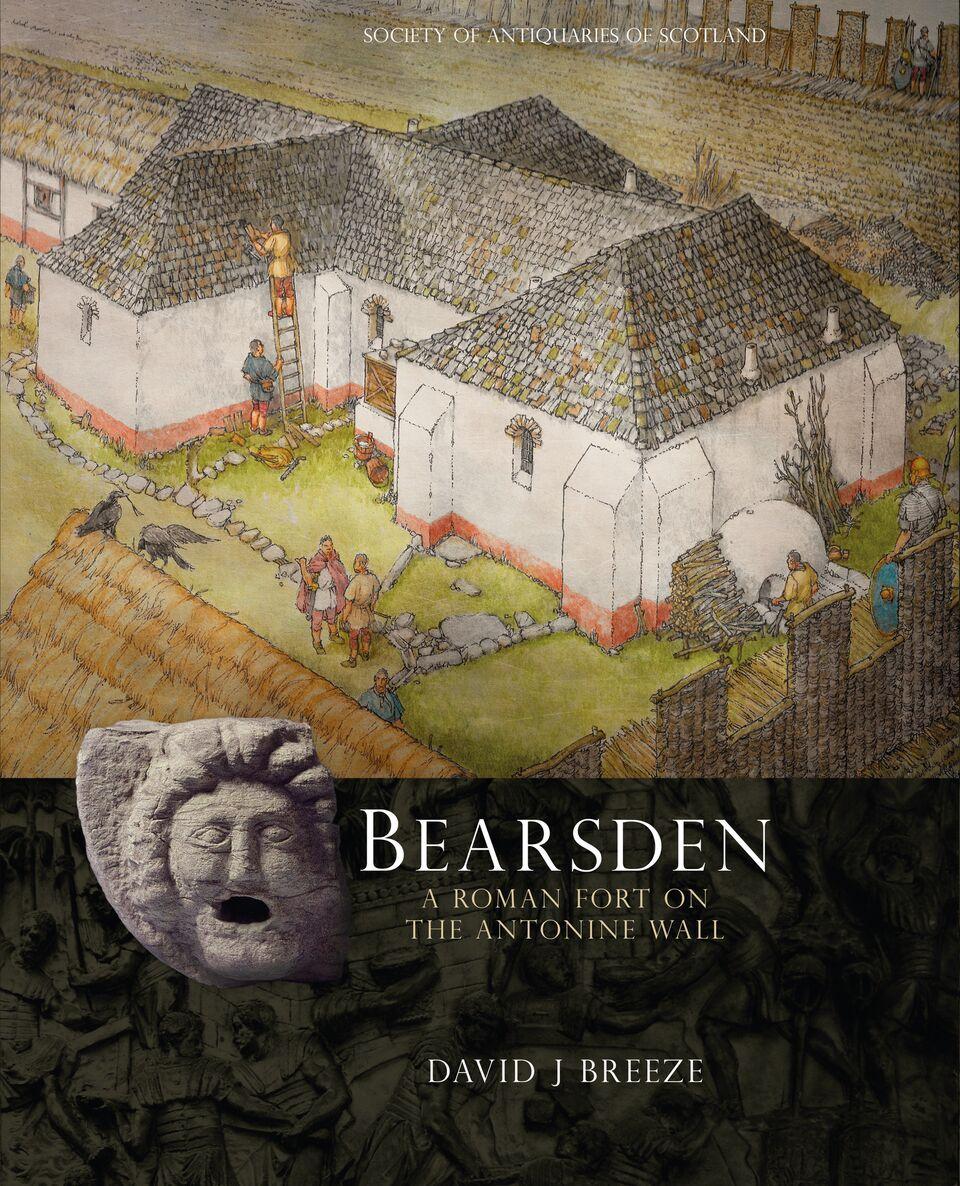

Written by Professor David Breeze, who led the research of the site for 10 years, and who was once named Archaelogist of the Year, the book which sums up the experience of discovering the large Roman fort in Bearsden in the 1970s.

Professor Breeze, now retired but based in Edinburgh, said that the soldiers cooked in their barracks using small braziers, a style of cooking from Africa.

They used celery for medicinal purposes, and opium poppy seeds on their bread.

The soldiers had wide-ranging but mainly vegetarian diet.

The soldiers, armed with swords, arrows and spears, also suffered from whipworm, round worm, and had fleas.

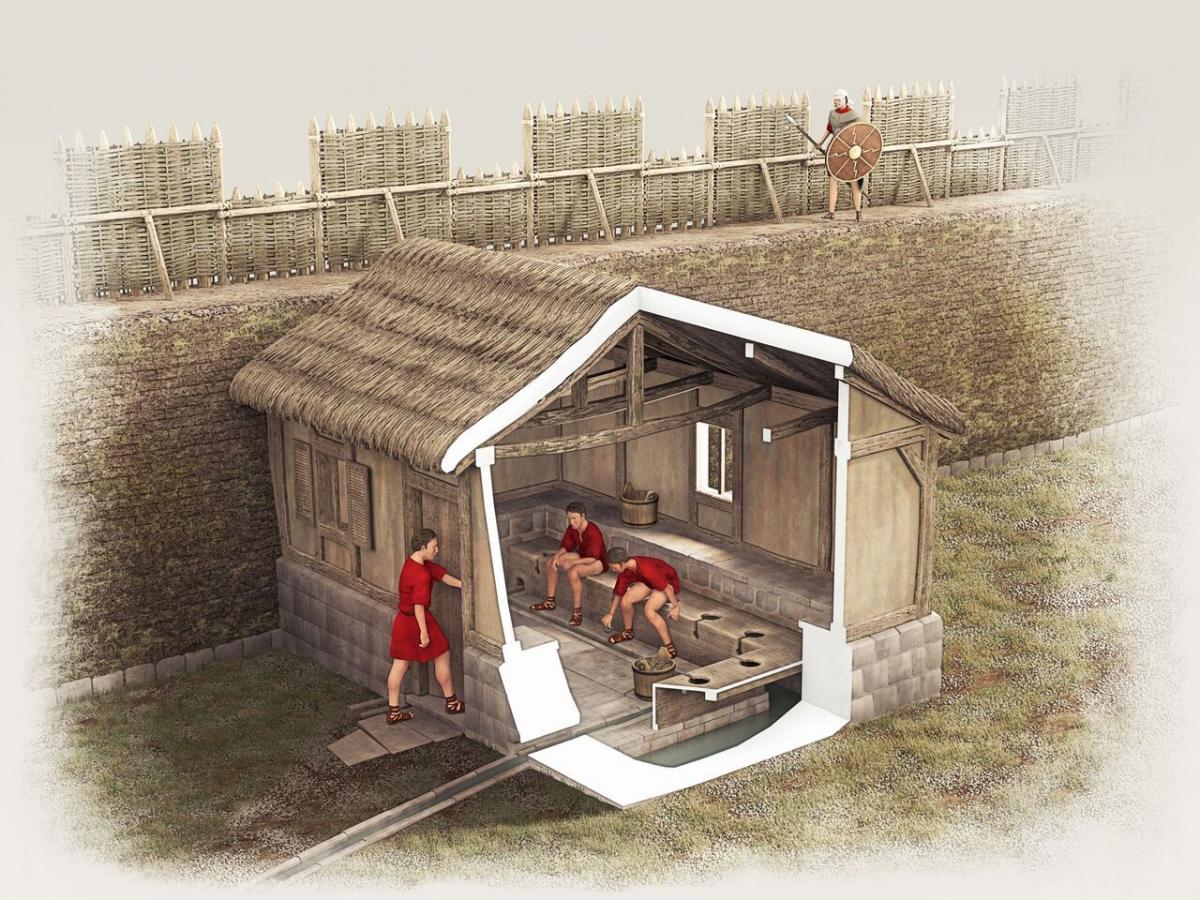

They would play games: a gaming board was found in the bath house at Bearsden.

The soldiers were stationed on the Antonine Wall for no longer than "a generation", to 165AD, he says.

Professor Breeze says he believes the wall, 99 miles north of Hadrian's Wall, was possibly intended to be permanent, but the defence, which ran from Old Kilpatrick on the west coast to near Bo’ness in the east, around 37 miles long, was abandoned when military policy changed.

It is not known what the Romans, whose troops may have included northern Brigantes men from south of the border, called Bearsden, but pottery was made by a firm called Sarrius, a company which evidently moved to Scotland to increase its trade.

Rssearch of the site was aided by painstaking analysis of residues, food remains, pottery and other items by the expert at the University of Glasgow.

The fort, excavated in the 1970s, also included a bath house and latrine.

Professor Breeze said: “We were very fortunate to discover sewage in a ditch, which was analysed by scientists at Glasgow University and demonstrated that the soldiers used wheat for porridge and to bake bread, and possibly to make pasta.

"It also told us that they ate local wild fruits, nuts and celery as well as importing figs, coriander and opium poppy from abroad."

The book, which is part-funded by Historic Environment Scotland and published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, focuses on a range of topics relating to the dig, with expert contributions from specialists in pottery, plant remains, soils, glass, insect remains, amongst other areas.

Dr Rebecca Jones, of Historic Environment Scotland said: "Despite their distance from Rome, the soldiers at Bearsden seem to have been far from detached from the rest of the empire, as evidence shows they regularly received commodities like wine, figs, and wheat from England, Gaul, and Southern Spain – as well as some locally gathered food.

"That’s just one of a number of exciting topics covered in Professor Breeze’s book, which is the culmination of years of hard work both on and off site."

Dr Jones added: "I’m sure that when the excavations were first taking place in the 1970s and 80s, nobody foresaw that the fort would become part of a World Heritage Site. This will be essential reading for anybody interested in the Roman occupation of Scotland."

The book was being unveiled at a launch hosted by Glasgow’s Hunterian Museum, where some of the artefacts discovered at Bearsden are on display, as part of their Antonine Wall exhibition.

The Antonine Wall was on the orders of the Emperor Antoninus Pius in the years following AD 140, the wall was both a physical barrier and a symbol of the Roman Empire’s power and control.

Bearsden: A Roman Fort on the Antonine Wall is available to buy via the Society of Antiquaries website.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel