WHAT IS in a name? Quite a bit, it seems, if you’re an Italian institution with several centuries of Papal patronage and the contours of nation building and 20th century political history etched into your fortunes. The Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia— and no, that title can’t be shortened (I did ask) — is heir to one of the oldest musical institutions in the world, a Roman academy founded in 1585 with Palestrina as one of its earliest members. Back then the name was even longer: the Congregazione dei Musici sotto l'invocazione della Beata Vergine e dei Santi Gregorio e Cecilia, or The Congregation of Musicians under the Invocation of the Blessed Virgin, Saint Gregory and Saint Cecilia. You get the sense they weren’t thinking of hashtagability for the digital age.

The opening weekend of this year’s Edinburgh International Festival features the Santa Cecilia orchestra (let’s work with that) who last visited to Scotland 68 years ago almost to the day. Back then the festival itself was just a bairn, founded out of the wreckage of the Second World War in the hope that art and internationalism could build a better world. Santa Cecilia gave six concerts on six consecutive nights under three different conductors including Wilhem Furtwangler. What a statement it was to invite an Italian orchestra and a German conductor, particularly one who had weathered a complicated relationship with the Third Reich. “With his scanty hair and long neck, he suggests an elderly bird of passage,” noted the Scottish Daily Mail on 9 September 1948. “Personally he is remote and aloof, wrapped in a manner which indicates: ‘I am the inestimable Furtwangler.’”

Santa Cecilia is the symphony orchestra of Rome and a rare thing in Italy as an orchestra not attached to any opera house, and one whose core repertoire comes not from the opera pit but from the Germanic symphonic tradition. Back in 1948 the Romans played Brahms Two and Three, Schumann Four, Beethoven Five. “One would not immediately think of Brahms and Schumann in connection with the performances of an Italian orchestra under an Italian conductor,” reflected The Scotsman on 11 September 1948, “but Vittorio Gui and the Augusteo Orchestra showed in the Usher Hall last night that there is, after all, nothing incompatible between the Italian temperament and the masterpieces of German romanticism.”

That Scotsman reference to the Augusteo reflects a brief period in the orchestra’s history when it occupied one of the finest concert halls in Europe: a 3,500 seat glory built above a mausoleum that housed some of the great Roman Emperors. Problem was, Mussolini had other plans for the mausoleum, eyeing it for the celebrations of the bimillennial anniversary of Emperor Augustus and as somewhere to rest his own noble bones when the time came. So the concert hall was destroyed in 1937, and although an architecture competition was held to resolve the dilemma of where to put the orchestra — some stunning arch-fascist plans were submitted — the Second World War got in the way. A new hall for the orchestra was delayed until Renzo Piano’s Parco della Musica opened in 2002, three hulking beetle pods clustered on the site of the 1960 Olympics in a northern suburb of the city.

Meanwhile orchestra’s calibre waxed and waned along with its various homes and political usefulness. Having been promoted after Italian unification as the pride of a new cosmopolitan nation — basically, Italians wanting to beat the Germans at their own game — only in the past decade has Santa Cecilia entered a new era of musical clout. Antonio Pappano took over as music director in 2005: a conductor born in London to Italian immigrants and an opera maestro who has been music director of the Royal Opera House Covent Garden since 2002. His heritage is unequivocally part of his musical DNA, but Santa Cecilia is Pappano’s first symphonic role and his first appointment in Italy. It’s been a good fit both ways.

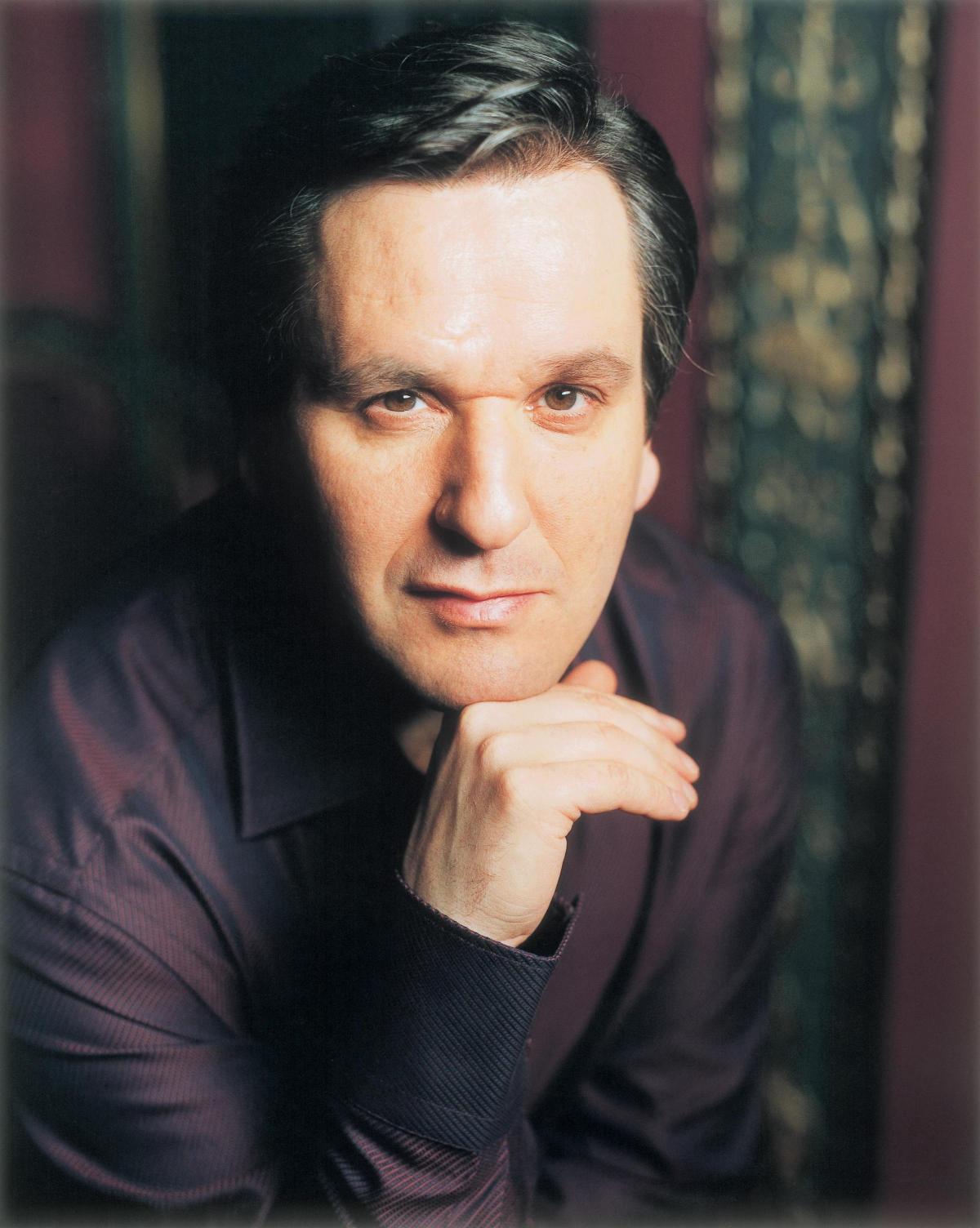

I meet the conductor after a concert in Rome, where posters on street corners declare his name in block capitals: clearly the cult of the maestro runs deep in the eternal city. He leads a fiery performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony, full of big drama and intensely singing lines, and after the concert his dressing room is thronged with benefactors and well-wishers. Our interview doesn’t start until well gone 11pm, despite the fact he’s flying back to London early the next morning to conduct Boris Godunov at the ROH.

When the crowd is finally ushered out and the dressing room door closes, Pappano flops onto a sofa wielding a large bottle of sparkling water. “Oh, it’s all part of the job,” he assures me. “These are the people who keep the orchestra going and I have to embrace the whole thing.” Part of the archaic peculiarity of Santa Cecilia is that it is still run by its Academicians: a list of 70 active and 30 honorary members graced by somewhat illustrious names. Honoraries include Argerich, Ashkenazy, Barenboim, Domingo, Glass, Gubajdulina, Kurtág, Pärt, Penderecki, Rattle. Actives count Chailly, Sciarrino, Morricone, Muti and Gatti (yes, they’re nearly all men) among their number.

And Pappano. “I was lucky to be voted in first time!” he smiles. “It’s a pretty byzantine process. Only the academicians can vote in new members and they have a whole marvellous politics of their own, especially when it comes to nominating a new president.” Potential presidents are described as ‘papabile’ — papal material. “They don’t quite use the white smoke but they might as well.” What’s crucial here is that Santa Cecilia is one of the only major organisations in Italy not run by a government figure. “Usually when the mayor of a town changes then the head of the opera house also has to go. Can you image the artistic upheaval? Whereas we can get on with things without political interference.”

Pappano describes the chemistry he’s built with the orchestra, the work he’s done to fitness the sound, the knock-on impact of that on Santa Cecilia’s status in broader Italian culture. “We’re getting more warmth from audiences than ever before. Part of that might be seeing the band’s relationship with me, part of it is hearing them get better, part of it might be the stability. People here usually laugh when you say that word.”

So what has changed in the orchestra’s playing? What remains the key to its sound? “Well, they’re a symphony outfit with opera in their DNA. That makes them special. They can sing and they can do drama. They play Rossini amazingly” — Rossini’s Stabat Mater is on the bill for EIF’s opening concert — “really capturing the wit and lightness and pizzaz. What we’ve been working on is how to sustain a deeper sound, how to get a symphonic homogeneity at the same time as the flexibility of an opera orchestra that can turn on a penny. We’re still learning how to do that.”

And for Pappano himself? “My role here makes sense in ways that run pretty deep,” he tells me. “I’ve learned a lot about people, a lot about Italians, a lot about Italy.” He’s learned good Italian, too: after the concert he gives a speech in what to me sounds a very convincing Roman brogue. “But most importantly, I’ve learned a lot about music. Because when I don’t have the trappings of costumes and all the other opera stuff, when it’s just me and the players and the audience, that’s when I really start to understand how an orchestra works.”

Antonio Pappano and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia are at the Edinburgh International Festival on August 6 and 7

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here