Here is former prime minister Tony Blair's statement in response to the release of the Chilcot Report:

The decision to go to war in Iraq and to remove Saddam Hussein from power in a coalition of over 40 countries led by the United States of America was the hardest, most momentous, most agonising decision I took in my ten years as British Prime Minister.

For that decision today, I accept full responsibility.

Without exception and without excuse, I recognised the division felt by many people in our country over the war, and in particular I feel deeply and sincerely - in a way that no words can properly convey - the grief and suffering of those who lost ones they loved in Iraq, whether members of our armed forces, the armed forces of other nations, or Iraqis.

The intelligence assessments made at the time of going to war turned out to be wrong, the aftermath turned out to be more hostile, protracted and bloody than ever we imagined.

The coalition planned for one set of ground facts, and encountered another. And a nation whose people we wanted to set free and secure from the evil Saddam became instead victim to sectarian terrorism.

For all of this I express more sorrow, regret and apology than you may ever know, or can believe.

Only two things I cannot say. It's claimed by some that by removing Saddam we caused the terrorism today in the Middle East, and that it would have been better to have left him in power. I profoundly disagree. Saddam was himself a wellspring of terror, a continuing threat to peace and to his own people.

If he'd been left in power in 2003 then I believe he would once again have threatened world peace and when the Arab revolutions of 2011 began he would have clung to power with the same deadly consequences that we see in the carnage in Syria today.

READ MORE: Calls for Tony Blair to face legal and political action on Iraq

Whereas at least in Iraq, for all its challenges, we have today a government that is elected, is recognised, is internationally legitimate, and is fighting terrorism with the support of the international community.

The world was, and is, in my judgement, a better place without Saddam Hussein.

Secondly, I will never agree that those who died or were injured made their sacrifice in vain. They fought in the defining global security struggle of the 21st Century against the terrorism and violence which the world over destroys lives and devastates communities and their sacrifice should always be remembered with thanksgiving and with honour when that struggle is eventually won as it will be.

I know some of the families cannot and do not accept this is so. I know there are those who can never forget or forgive me for the having taken this decision and who think that I took it dishonestly.

As the report makes clear there were no lies, Parliament and Cabinet were not misled. There was no secret commitment to war, intelligence was not falsified and the decision was made in good faith.

However, I accept that the report makes serious criticisms of the way decisions were taken and again I accept full responsibility for these points of criticism even where I do not fully agree with them.

I do not think it is fair or accurate to criticise the armed forces, the intelligence services or the civil service.

READ MORE: Tony Blair takes responsibility for Iraq 'mistakes' but made in 'good faith'

It was my decision they were acting upon.

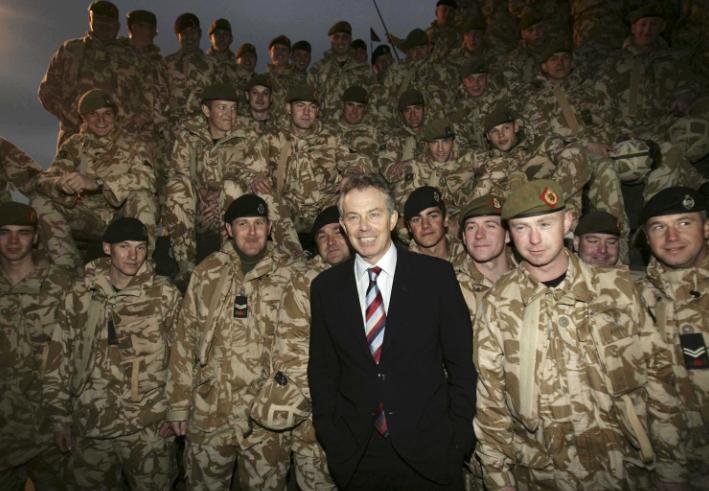

The armed forces in particular did an extraordinary job throughout our engagement in Iraq, in the incredibly difficult mission we gave them. I pay tribute to them, any faults derived from my decisions should not attach to them.

They are people of enormous dedication and courage and the country should be very proud of them.

Today is therefore the right moment to go back however, and look at the history of that time so that those, even if they passionately disagree, will at least understand why I did what I did, and learn lessons so that we do better in the future.

First: Why was Saddam a threat? My Premiership changed completely on September 11 2001. 9/11 was the worst terrorist atrocity in history.

Over 3,000 people died that day in America, including many British people, making it the worst ever loss of life of our own country's citizens from any single terror attack.

In fact, 9/11 was not of course the first terror attack. Prior to then, 23 countries had suffered terrorist attacks of this nature: in 2002, 20 different nations lost people to terrorism.

For over 20 years as well, the regime of Saddam had become a notorious source of conflict and bloodshed in the Middle East.

He had attempted a nuclear weapons programme, only halted by a preventive strike by the Israeli military in 1981, and used chemical weapons in the war he began with Iran, a war which lasted seven years with around a million casualties.

Out of the Iranian experience came Iran's own nuclear weapons programme.

He invaded Kuwait in 1990, he used chemical weapons extensively against his own people, for example in the massacre of Halabja where thousands died in a single day.

The international community made frequent attempts to bring him into compliance with UN resolutions, calling for him to give up his programmes.

As at March 2003 he was in breach of no fewer than 17 such UN resolutions.

In 1998, following the ejection of UN weapons inspectors from Iraq, President Clinton and I authorised military strikes on his facilities and from that point regime change in Iraq became the official policy of the US administration.

In a country where a majority of Iraqis, Shia Muslims and 20 per cent of the population of Kurds, he ruled with an unparalleled brutality with a government drawn almost exclusively from the Sunni 20% minority, though many of his victims were also Sunni.

Saddam was not the only developer of weapons of mass destruction.

Libya had a programme, North Korea was trying to obtain nuclear technology.

The network of the Pakistani scientist AQ Khan was an active proliferator of such techonology and Iran's program had begun.

But only one regime had actually used such weapons. That of Saddam.

Intelligence still valid indicated al Qaida wanting to acquire such material and 9/11 showed they were prepared to cause mass casualties.

So it's important now that we're here, 15 years after 9/11, to recall the atmosphere at that time.

America had never suffered such an attack on its own soil before. Its population were devastated. They regarded themselves at war.

The Taliban who had given sanctuary to al Qaida had been removed from power in Afghanistan in November 2001.

But the 2002 Bali bombings, in which over 200 victims, mainly Australians, lost their lives, showed the continuing threat. All western nations were changing their security posture, we were in a new world.

And at that time we did not know where the next attack, threat or danger would come from. The fear of the US Administration which I shared was the possibility of terrorist groups acquiring, either by accident or design, chemical weapons, biological weapons, or even a primitive nuclear device.

The report accepts that after 9/11 the calculus of risk had changed fundamentally. We believed we had to change policy on nations developing such weapons in order to eliminate the possibility of WMD and terrorism coming together.

Saddam's regime was the place to start.

Not because he represented the only threat, but because his was the only regime actually to have used such weapons, there were outstanding UN resolutions in respect of him, and his record of bloodshed suggested he was capable of aggressive, unpredictable, catastrophic actions.

In addition, the UN sanctions imposed on Iraq were crumbling and therefore containment was faltering.

The final Iraq survey report which was conducted into Saddam's WMD programme and ambitions after the Iraq war, and whose findings are accepted in this report, found that Saddam did indeed intend to go back to developing the programmes after the removal of sanctions.

So I ask people to put themselves in my shoes as Prime Minister.

Back then, barely more than a year from 9/11, in late 2002 and early 2003, you're seeing the intelligence mount up on WMD.

You're doing so in a changed context of mass casualties cause by a new and virulent form of terrorism.

You have at least to consider the possibility of a 9/11 here in Britain and your primary responsibility as Prime Minister is to protect your country.

These were my considerations at the time.

The lead up to war - there was no rush to war.

The inquiry rightly dismisses the conspiracy theory that I pledged Britain unequivocally to military action at Crawford, Texas, in April 2002.

I did not and could not, as they explicitly in their report conclude.

I was absolutely clear publicly and privately however that we would be with the USA in dealing with this issue, and I made that clear in the note to President Bush of the 28th of July 2002. But I also said we had to proceed in the right way and I set out the conditions necessary, especially, that we should then go down the UN route and avoid precipitate action as indeed the inquiry report finds.

So, as again the inquiry finds, I persuaded a reluctant American administration to take the issue back to the UN. This resulted in the November 2002 UN Resolution 1441 giving Saddam 'a final opportunity' to come into 'full and immediate compliance with UN Resolutions' and to cooperate fully with UN inspectors.

Any non-compliance was defined as a material breach.

Finally, and only under threat of military action, Saddam permitted inspectors to return but his co-operation was neither full nor immediate - see the report of the inspectors to the UN in January 2003 and that of the 7th March 2003, again referred to in the body of the report.

However, by then there was substantial disagreement at the UN Security Council. America wanted action, President Putin and the leadership of France did not.

In a final attempt to bridge the division I agreed with the inspectors a set of six tests based on Saddam's non-compliance with which he had to comply immediately, which included things like interviews with those responsible for his programme and which up to then had been refused except in a country where obviously these people would be subject to intimidation.

So these six tests were drawn up in a resolution accompanied by an ultimatum that non-compliance would result in military action.

So again I secured American agreement to a new resolution, vetting tests which if he had passed would have avoided military action.

But the United States understandably insisted that in the event of continued failure, the UN had to be clear that action would follow. And this was the approach rejected by Saddam.

The Americans and the UK and other partners from over 40 nations had assembled a force in the Gulf ready for military action.

President Bush made it clear he was going to act.

The British Government, under my leadership, chose to be part of that action, a decision endorsed by Parliament, with the leaders of the opposition being given access to exactly the same intelligence and advice as given to me.

Now, the enquiry finds that as at the 18th of March, war was not, and I quote, the "last resort".

But given the impasse of the UN and the insistence of the United States for reasons I completely understood, and with hundreds of thousands of troops in theatre which could not be kept there indefinitely, it was the last moment of decision for us, as the report indeed accepts.

However, as at the 18th of March, there was gridlock at the UN.

In resolution 1441 it had been agreed to give Saddam one final opportunity to comply.

It was accepted he had not done so. In that case, according to 1441, action should have followed.

It didn't because by then, politically, there was an impasse.

I say the undermining of the UN was in fact refusal to follow through on 1441, and with the subsequent statement from President Putin and the President of France, that they would veto any new resolution authorising action in the event of non-compliance, it was clearly not possible to get a majority at the UN to agree a new resolution.

As the then president of Chile explained there was no point since any decision by a majority would be vetoed.

So, on the 18th of March, and this is the vital thing to understand, given especially what Sir John said this morning, we had come to the point of binary decision: right to remove Saddam or not, with America or not.

The report itself says this was a stark choice, and it was. Now the inquiry claims that military action was not a last resort, though it also says it might have been necessary later.

With respect, I didn't have the option of that delay. I had to decide. I thought of Saddam, his record, the character of his regime.

I thought of our alliance with America, and its importance to us in the post 9/11 world, and I weighed it carefully.

I took this decision with the heaviest of hearts. I have, already as the inquiry finds, consulted our armed forces and received their commitment to be part of it and their view that we should be part of it.

If you read my private notes to President Bush from March 2002 onwards you will see my caution, my recognition this was not like Kosovo or Afghanistan, and my desire to do this if at all peacefully.

But as of 17 March 2003 there was no middle way, no further time for deliberation, no room for more negotiation. A decision had to be taken and it was mine to take as a Prime Minister.

I took it. I accept full responsibility for it. I stand by it.

I only ask with humility that the British public accept that I took this decision because I believed it was the right thing to do based on the information that I had, and the threats perceived, and that my duty as Prime Minister at that time in 2003 was to do what I thought was right, however imperfect the situation or indeed the process.

At moments of crisis such as this, it's the profound obligation of the person leading the government of our country to take responsibility and to decide. Not to hide behind politics, expediency or even emotion.

But to recognise that it is a privilege above all others to lead this nation.

But the accompaniment of that privilege when the interests of our nation are so supremely and plainly at stake is to lead and not to shy away.

To decide and not avoid decision. To discharge that responsibility and not to duck it.

Neither history, not the fearsome raucous conduct of modern politics, with all its love of conspiracy theories and its willingness and addiction to believing the worst of everyone, should falsify my motive in this. I knew it was not a popular decision.

I knew what its costs might be politically, even though that shrinks into complete insignificance beside the human cost.

I did it because I thought it was right, and because I thought the human cost of inaction, of leaving Saddam in power would be greater for us and for the world in the longer term.

So the action commenced on the 18th of March, in less than two months, American and British armed forces, and those of other nations, successfully deposed Saddam.

And that part of the campaign, which was after all a major part of our strategic objectives, was brilliantly conducted by our military and we should never forget that.

In June 2003, a UN resolution was agreed, putting the coalition forces in charge of helping the country to a new constitution with UN support and under a UN mandate.

In August 2003, the UN mission had to withdraw however, following the bombing of the UN headquarters in Baghdad by al Qaida. And in 2004 the country slid into chaos and instability, especially following the al Qaida bombing of the Samarra Shia mosque.

A state of near civil war continued until the surge of American forces began in 2007 which restored the country to relative calm.

In 2010, a largely peaceful election, in which the party with the most votes was a non-sectarian coalition, was held.

And in 2010, Al Qaida in Iraq was effectively defeated. In 2011, the Arab spring began.

The remnant of Al Qaida Iraq, left for Syria, built its space in Raqqa, and then came back over the border into Iraq renamed as Isis, and helped by the sectarian nature of the Maliki government, exploited the situation in Iraq and created what we see today.

We should never forget that as a result of the removal of Saddam in 2003, Libya agreed to yield up its nuclear and chemical weapons programme.

This led to the complete destruction of the programme under international inspection, which turned out to be much more advanced than we knew, which had it remained in the hands of Gaddafi, would have itself posed a serious threat.

The AQ Khan network was shut down.

I come to our alliance with America.

Whilst the inquiry accepts it was my prerogative as Prime Minister to be with the United States in military action, the inquiry questions whether this was really necessary and the importance I attached to the alliance.

9/11 was an event like no other in US history. I considered it an attack on all the free world. I believed that Britain as America's strongest ally should be with them in tackling this new and unprecedented security challenge.

I believed it important that America was not alone but part of a wider coalition. In the end, even a majority of European Union nations supported action in Iraq.

I do not believe that we would have had that coalition, or indeed persuaded the Bush administration to go down the UN path, without our commitment to be alongside them in that fight.

Throughout my time as Prime Minister first with the Clinton administration and then with the Bush one, Britain was recognised as the United States' foremost ally. It served us well in Kosovo, and allowed us to protect more innocent people than we could have alone.

We were America's core partner in the post-9/11 world and I believe that was right.

I believe there are two essential pillars to British foreign policy, our alliance with the United States and our partnership in Europe, and we should keep both strong as a vital national interest.

People can disagree with that but that was my judgement as Prime Minister.

I come to Saddam and weapons of mass destruction. For more than half a decade I've always apologised for the inaccurate intelligence - in particular for the intelligence that Saddam had a stockpile of chemical weapons.

The inquiry endorses the findings of both the Hutton inquiry and the Butler inquiry that there is no evidence that intelligence was improperly included in the September 2002 dossier or that Number 10 improperly influenced the text.

But though it makes no finding of impropriety it finds that the intelligence had not established beyond doubt that Saddam possessed WMD.

I only ask that people read the reports given to me, first in March 2002 and then in September 2002 and on many other occasions, for example, in the note written by my senior adviser days before military action.

In hindsight we may know that some of this information was not correct, but I had to act on the information I had at the time.

I would point out two other things, first that virtually every intelligence agency had reached the same conclusion and for very good reasons: Saddam's previous use of weapons, his complete disregard for the mass destruction of human life, and the eviction of UN inspectors in 1998.

Secondly, it is essential to consider the findings of the Iraq Survey Group. Conducted by leading UN weapons inspector with 1,400 people in his team.

This was done after the war in 2004 on the basis of interviews including with Saddam himself and his leading officials. The very interviews denied the inspectors in 2003.

It's right to read that report, because it is authoritative. The inquiry itself calls it significant. But with respect to them they never explained its significance.

The Survey Group finds that Saddam's priority in the late 1990s and 2001 to 2003 was to get sanctions lifted. But once they were lifted they find it was his intent to reconstitute his programme since he believed it to be essential to his personal and political survival.

Above all, this survey group report finds that he intended to go back to a nuclear programme, fearing the Iranian development of nuclear weapons, and that he kept his teams and capability to develop those, and chemical weapons, once sanctions were removed.

Now of course, we can never know whether he would have done this.

But I ask; If you knew for a fact this dictator had used chemical weapons on his own people and those of other nations, for a fact had lied about having them so he could continue to produce and use them, and for a fact that he had killed thousands of his own people and those in other countries with no respect whatever for human life or norms of normalised behaviour, would you have wanted to take that risk of leaving him in place? Or would you have wanted to eliminate it?

Saddam in my view was going to pose a threat for as long as he was in power.

Now the planning and the aftermath.

The inquiry makes several criticisms of the planning process for the aftermath of the invasion. I accept that especially in hindsight we should have approached the situation differently.

These criticisms are significant. They include failures to seek assurances and better planning from the American side, which I accept should have been sought.

The failures in American planning are well documented and accepted.

I do note, nonetheless, that the inquiry fairly and honestly admit that they have not even after this passage of time been able to identify alternative approaches which would have achieved greater success.

And this, I would suggest, is for the very simple reason that the terrorism we faced and did not expect would have been difficult in any circumstances to counter. This is the lesson we learn from other conflict zones, especially Libya, Syria, Yemen, and others also.

Our planning proceeded on the basis of those risks of which we were principally warned, namely the possibility of humanitarian disaster, the use of WMD by Saddam, resistance from the regime, and the challenges of reconstruction.

In the event though, the report does not deal with this in detail, the real problems were those caused by terrorism, and from quarters we did not expect.

Al Qaida, whose attacks on the UN, on reconstruction on the Shia population, tipped the country to the brink of civil war in 2004 and 2006 IED attacks and other acts of terrorism from the Shia militia, supported by Iran.

The inquiry does find that there were warnings about sectarian fighting and blood-letting, I accept that, but I would point out that nowhere were these highlighted as the main risk, and in any event what we faced was not the anticipated internal blood-letting, but an all-out insurgency stimulated by external arms and money.

We also now know that the Assad regime in Syria was deliberately sending terrorists across the border to cause terror and instability, and this had a major impact on the coalition's ability to make progress in the country.

In short, we ended up fighting exactly the same elements that we're fighting everywhere in the world today from the same origins - Shia extremism on the one hand and Sunni extremism on the other.

The consequence was that as we were trying to rehabilitate the country those elements were trying to wreck our efforts by sectarian violence and that is what we did not foresee.

The inquiry finds that in particular in January 2003 there were no full options papers presented to Cabinet.

I note that Cabinet alone debated Iraq 26 times in the run-up to conflict.

There were 28 meetings of the ad-hoc committee with relevant ministers present.

However I accept I could have, and should have insisted on the presentation of a formal options paper to Cabinet.

I come to the legality. The report does not make a finding on the legal judgment of the then attorney general.

There are very good reasons for not disputing it. The whole negotiating history of resolution 1441 in the UN made it clear the US and the UK had always refused language that obliged a second resolution.

The defining of the obligations of Iraq and the agreement that failure fully and immediately to comply was a material breach was a reasonable basis for action.

The advice of the attorney general was in line with that of other law officers in other nations and distinguished legal experts though I fully acknowledge and respect that others took a different view.

Where the politics is hotly contested the law will be also.

I understand why the inquiry finds that the process of coming to legal opinion was far from satisfactory but it does not alter the legal conclusion.

It was after the detailed meetings the Attorney General had with US and UK officials, explaining the negotiating history of 1441 that he came to the view that it was not necessary for a second resolution.

On the 27th of February he gave that view orally, on the 7th of March he provided that advice in writing. I accept in retrospect it would have been better to have provided the full written advice to Cabinet, that this was not the legal precedent and in any event was not requested by the Cabinet.

I accept there is a case for providing it to Parliament. But none of these matters of process alter the fact that his advice in the end was clear and is not challenged by the inquiry.

The inquiry at one point said there was no indication of why I gave my view to the attorney general that Saddam as of the 13th of March 2003 was in material breach of 1441.

As the attorney general has explained, my view is not legally necessary since 1441 had determined what constituted a breach. But nonetheless he sought my confirmation of what I thought.

Saddam was accepted by everyone including the inspectors not to be fully complying - he had a long history of deception.

The whole basis of my six tests was to address the failure to comply.

Indeed intelligence that is still considered valid, shows Saddam, at the time in breach of UN resolutions, instructing his officials to remove any evidence of WMD or programmes for its development.

The issue was rather whether despite the breach, he should be given more time.

I accept, of course, it is better politically, if the Security Council makes such a determination. But by then, given the position in the security council, given the fundamental disagreement, it was clear there would be no agreement, irrespective of the circumstances.

I come to this important point: is the world safer or less safe as a result of the removal of Saddam in 2003?

The report never deals with this issue in specific terms. But again with respect to the inquiry, this issue has to be debated if we're to reach a conclusion on the wisdom of the judgement I made.

I ask that fair-minded people at least consider the following: If we had withdrawn the threat of action in 2003 and pulled back our forces, we would have found it almost impossible to reassemble those forces in that number.

Now Sir John says today that it might have been necessary to take military action later. He accepts that. But I don't see how we would have reassembled that force. Sanctions would have swiftly eroded over time I would suggest.

It would have been hard to have kept an invasive process of inspection in place.

So Saddam would have remained, and immensely politically strengthened. Plus he would have had the benefit of a hundred dollars a barrel oil.

This is where the Iraq survey group is so important. It indicates that he would have resumed his earlier development of nuclear and chemical weapons.

If that is conceivable, as it surely is, then his removal avoided what would otherwise have been an unacceptable risk in my judgment.

I acknowledge completely and I respect the other point of view, I simply ask that people respect my point of view, and the judgment I took, on the facts I had, at the time.

We then come to the state of Iraq today, because it's still engaged in conflict - a conflict that goes on all over the Middle East.

But to those who say but for the action of 2003 Iraq would be peaceful in 2016 I ask them to consider the following:

There is no doubt that the sectarian policies of the Maliki government contributed to the renewed conflict in Iran, but the decisive event of the last five years in the Middle East is the Arab Spring which began in 2011.

Starting in Tunisia regimes across North Africa and the Middle East were toppled or put under sustained attack.

In the case of Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and Yemen the regimes fell. Then in early 2011 the revolt of the Syrian people against the Assad regime began.

In Syria, as with the Saddam regime in Iraq, effectively a small minority ruled the majority on sectarian lines.

Except in this case, in the case of Syria, with the Sunni in the majority.

Between 2003 and 2011, by the way, all of those regimes had remained in power, not one of them had changed.

So supposing Saddam had stayed in power in 2003, I ask this counterfactual: Is it likely that he would still have been in power in 2011 when the Arab Spring began?

Is it likely that the Iraqi people would have joined the Arab Spring when all the countries were part of it and this was the most tyrannical regime of any of them, with the vast majority of people excluded from power?

And is it likely that if the Iraqi people had revolted, if there had been an uprising, that he would have reacted like Assad in Syria?

Surely it is at least possible that the answer to all of those questions is affirmative. In that case, the nightmare of Syria today would also be happening in Iraq, except with the Shia/Sunni balance inverted. Consider the consequences of that.

Even if you disagreed with removing Saddam in 2003, we should be thankful we're not dealing with him and his two sons now.

Saddam was himself deeply sectarian. As the latest research shows the leadership of the regime was heavily sectarian and deliberately made so.

And to those who think removing Saddam was the cause of the turmoil in the Middle East and there is some unbroken line between the removal of Saddam in 2003 and what is happening in Iraq today, I say the following.

After the surge of 2007, Al Qaida was defeated and marginalised.

In 2010 Iraq was relatively stable.

It was in Syria, after the Arab Spring, when AQ became Isis, head-quartered in Raqqa. Syria where we failed to intervene, Syria the very opposite of the policy of intervention, where more people have died than in the whole of Iraq, with the worst refugee crisis since World War Two and with no agreement as to the future.

At least for all the challenges in Iraq today, there is a government actually fighting the terrorism and doing so with Western support, internationally recognised, including by Saudi Arabia and Iran, as a legitimate government, and with a Prime Minister welcome in the White House and in capitals across the globe.

None of this excuses the mistakes we made. None of this excuses the failures, for which I repeat I take full responsibility, and apologise.

But it shows, that in the uncertain and dangerous world we live in, all decisions are difficult.

Each has consequences predicted and unpredicted, and the only thing a decision maker can do, is to take those decisions on the basis of what they genuinely believe to be right and that is what I did.

In the final passage I will draw a few lessons from this conflict and then conclude and then take your questions for as long as you wish to ask them.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel