On September 24 2002 the UK Government published a dramatic assessment of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

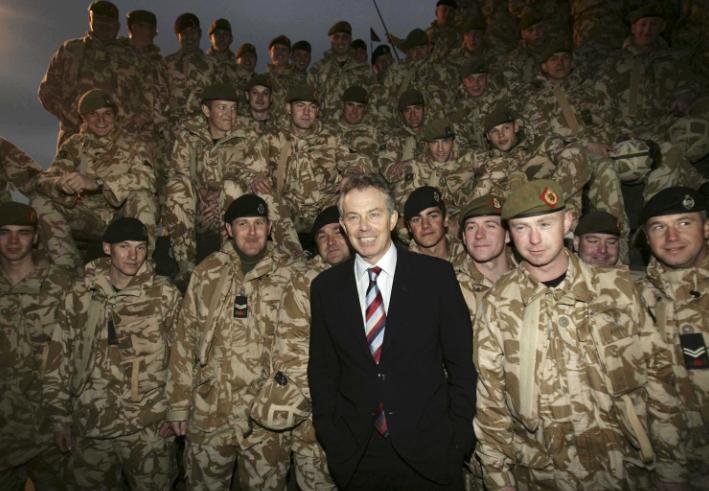

Included alongside the dossier was a foreword by the then Prime Minister Tony Blair, which said that some WMD would be "ready within 45 minutes of an order to use them".

It was on the back of "flawed" intelligence like this that the 2003 British invasion of Iraq was launched, an almost seven year long official inquiry has concluded.

More than 200 British citizens would die in the conflict, as well as, by July 2009, at least 150,000 Iraqis, most of them civilians.

The Chilcot report reveals a damaging litany of failures in the run up to the invasion, the war itself and its aftermath.

The drumbeat to war caused Mr Blair and others to overestimate their abilities and lose perspective.

Soldiers were left without necessary equipment, including helicopters.

Britain's military role would eventually end "a very long way from success" forced to do "humiliating" deals over hostages with local militia to bring attacks on British forces in Iraq to an end.

And even the intelligence ministers could have been entirely fictional - and dreamt up by a Hollywood filmmaker.

The report found that "questions were raised (within the intelligence services) about the mention of glass containers...

“It was pointed out that glass containers were not typically used in chemical munitions; and that a popular movie (the 1996 film The Rock starring Sean Connery) had inaccurately depicted nerve agents being carried in glass beads or spheres."

Yet the report shows that in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks Mr Blair urged then US President George Bush not to be hasty over Iraq.

The country was run by a brutal dictator, Saddam Hussein.

But there was nothing to specifically to link him to the terror attacks.

However, the report found, by November 2001 the UK Government had changed its tune.

Mr Blair was now advocating a "clever” long-term strategy that could eventually lead to regime change in Iraq.

By the time of the now infamous meeting at the Prairie Chapel Ranch in Crawford, Texas, in April 2002, there had been a further change.

Mr Blair had been advised that Saddam would not leave without force and within the UK Government contingency plans were already underway for a potential invasion.

The former Prime Minister has faced accusations that he told Mr Bush in Crawford that the UK would back him, no matter what.

Sir Christopher Meyer, the British ambassador to the US at the time, told the inquiry that it was "not entirely clear to this day … what degree of convergence was, if you like, signed in blood at the Crawfordranch".

Mr Blair has denounced as a "myth" and that the two men agreed to look at the idea of a UN Security Council resolution to present Saddam with a clear choice, either weapons inspectors back in or face the consequences.

In July that year, however, months before MPs approved military intervention, Mr Blair sent Mr Bush a message entitled ‘Note on Iraq’.

It began: “I will be with you, whatever”.

On Saddam, Mr Blair added: “He could be contained. But containment... is always risky”.

However, the Labour leader did demand action on three key areas – the Middle East peace process, work on UN support and a shift in UK public opinion.

He told the president: "In Britain right now I couldn't be sure of support from Parliament, Party, public or even some of the Cabinet. And this is Britain. In Europe generally, people just don't have the same sense of urgency post 9/11 as people in the US."

The Labour leader also stressed the the importance of trying to establish a link with al Qaida in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks - none was ever found.

In December, however, Mr Bush decided that inspectors were destined to fail and resolved to go to war.

By the end of the following January, according to the report, Mr Blair had accepted that timetable.

There was another attempt at a UN resolution, but by March it was clear that most counties in the security council opposed the idea.

Afterwards Mr Blair and his foreign secretary Jack Straw blamed France.

But the report disagrees.

It accuses the UK Government of "undermining" the authority of the UN Security council with the march to war.

Its damning conclusion is that the peaceful options were not exhausted.

Military action in Iraq might have been necessary at some point, but in 2003 there was no "imminent threat".

So what then of the WMD?

The report found that the "flawed" intelligence given to Mr Blair was “not challenged and ...should have been".

The inquiry found that some in the intelligence community had started with the belief that Saddam possessed WMD.

Mr Blair told MPs said at some point in the future the threat posed by the weapons "would become a reality".

But the report sound that his comments and the dossier released that day – which would later face accusations that it had been ‘sexed up’ by his press chief Alastair Campbell – were presented to MPs with a “certainty that was not justified”.

As long as sanctions remained effective Iraq could not develop nuclear weapons.

After the invasion Mr Blair told MPs that Saddam may not have had stockpiles of weapons but that he had the intent and capability to develop them.

But as the report points out that was not the explanation for military action before the conflict.

Chilcot is also scathing of the "far from satisfactory” way ministers concluded there was a legal basis for war.

The crucial judgment was that Iraq had breached the terms of a UN Security Council resolution.

Attorney General Lord Goldsmith initially told Mr Blair he would need another resolution confirming Baghdad's failure to comply with disarmament demands.

This draft advice was withheld from Cabinet ministers and not seen by Mr Straw or defence secretary Geoff Hoon.

Following discussions with the US - who were adamant no extra resolution was needed - Lord Goldsmith said "a reasonable case" could be made.

This centred on claims resolution 1441 allowed for military force under an earlier resolution during the 1990 Gulf War.

However, "the safer route" was another resolution, as "hard evidence" Iraq was not co-operating would be needed from UN weapons inspectors.

When word of this advice emerged Lord Goldsmith was asked by Chief of Defence Staff Admiral Sir Michael Boyce to give "clear-cut" assurances military action would be lawful.

But within days Mr Blair's staff noted it was now his "unequivocal view" Iraq was in breach of its obligations.

The report found it was "unclear what specific grounds Mr Blair relied upon in reaching his view" and noted that there was "no reference" to him seeking the views of weapons inspectors.

The issue should have been examined by a Cabinet Committee before being endorsed by Cabinet.

What the Cabinet was presented with, just days later, was a new assessment from Lord Goldsmith that the government believed it was "plain" Iraq was in breach of resolution 1441 and that there was no need for a second resolution.

The report found the Cabinet was "not misled" and that there was no "side deal" between Mr Blair and the Attorney General.

It adds, however: "Given the gravity of this decision, Cabinet should have been made aware of the legal uncertainties".

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here