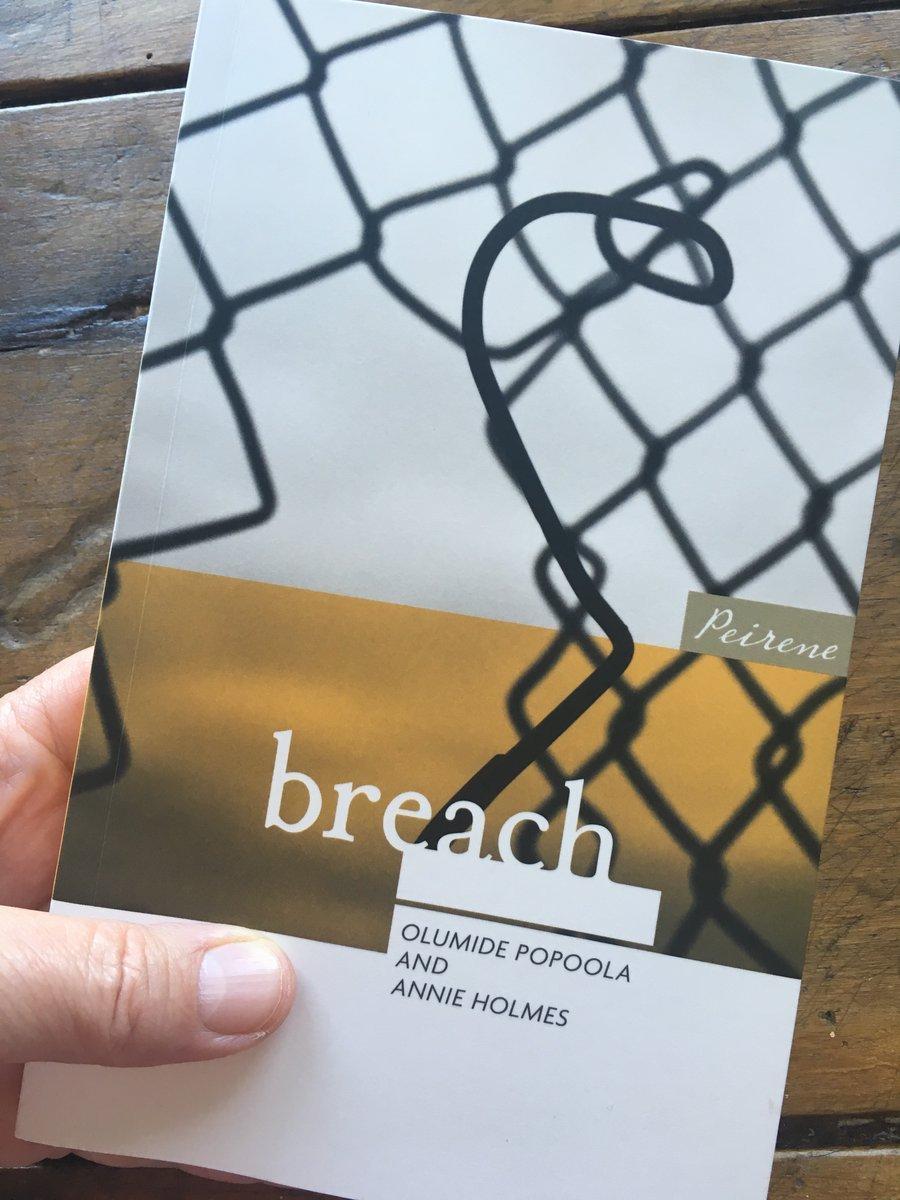

Breach

Olumide Popoola and Annie Holmes

Peirene Press, £12

Review by Malcolm Forbes

TWO weeks into the EU referendum, surveys showed that immigration had leapfrogged the economy to become the main factor driving the leave vote. Sifting the grubby lies, casual generalisations and hysterical scare stories churned up in the wake of Brexit, one pertinent truth about immigration emerged: namely that anxiety about immigration held greater sway among voters than immigration itself. Fear, then, won the day.

How effectively the flames of fear were fanned by the false threat of an imminent Turkish invasion following EU membership, or the cheap press-ganging of Syrian migrants into poster-people to illustrate a “breaking point”, belongs to another discussion. Suffice it to say, Brexit won’t completely kill off that fear, for asylum seekers will continue to come here, either in legally decreed quotas in accordance with the UN Refugee Convention, or in illegal dribs and drabs via Calais.

An insightful new book chronicling the plight of refugees in the so-called Calais Jungle ought to be mandatory reading for anyone troubled by the crisis or mistrustful of Johnny Foreigner. Breach is the first title of Peirene Press’s new imprint Peirene Now!, a series which, according to the blurb, will engage with current political hot-topics. The book arrives at a timely juncture and tackles head-on the hottest topic for years.

Peirene’s publisher, Meike Ziervogel, explains at the beginning of Breach that she commissioned its two UK-based authors, Nigerian German Olumide Popoola and Zambia-born Annie Holmes, to visit the Calais refugee camps “to distil stories into a work of fiction about escape, hope and aspiration.” Both have produced four tales apiece which, cumulatively, urge us to appreciate our own comfort and security, and force us to look afresh and attentively at a calamity that is worsening on our doorstep.

The first story, Popoola’s ‘Counting Down’, tracks the jagged route and fluctuating fortunes of a group of Calais-bound migrants. All have “survived the boat” and “survived the crazy people who want to keep their beach clean, free of refugees”. They share anecdotes and advice (“Italy is like Greece. Collapsed.”), pool their resources and pick up fellow travellers on the way. But when money goes missing, it becomes clear that one of their number has a separate agenda and is only looking out for himself.

Holmes’ first tale, The Terrier, is narrated by Eloise, a French woman who has opened her door to two Kurdish refugees. Every day, after a warm, safe night in Eloise’s home, Omid and his sister Nalin go to the jungle to assist others and mingle with friends. For a while Eloise keeps them and the “filth and disease” of the camp at arm’s length, preferring to lose herself in laundry and pick fruit in her orchard. But gradually, after absorbing the siblings’ account of their arduous flight to freedom and the parlous conditions of the jungle, she takes an interest, drives to the camp and enters their world.

For Eloise, the camp’s fenced-in inhabitants resemble “figures from history or documentaries…like second-hand memories of war.” She recalls watching them trudge across Eastern Europe on the news: “it was something more brutal, like a forced march.” Popoola reaches for different imagery in Lineage. “The Jungle is like a laboratory,” one man says. “You have to live with people, get along.”

If there is a chink of light in these stories it is indeed the sight of all walks of life getting along – coming together and creating a ramshackle but functioning community within the confines of the camp. Several stories, including the cruelly-titled Paradise, depict an attempt at normality. Volunteers and refugees build makeshift schools and hospitals or congregate at the Afghan café. Musicians on a stage, stinking toilet cabins and a tent emblazoned with a marijuana leaf with an accompanying sign saying "Keep on the grass" turn a squalid holding-pen into a rough-and-ready music festival.

However, that sanitised gloss can only conceal so much. Spies and smugglers prowl the camp for desperate victims. Women sell themselves to truck drivers. Stowaways endure cold, airless mobile prisons. One man believes London will be “a place of angels”. A fire in the camp prompts one Calais local to say “Maybe this is the only way to get rid of them – smoke them out.”

Despite masquerading as fiction, all eight stories feel like reportage, a succession of stark snapshots of real lives. They are neither plot-driven nor adorned with stylistic tricks. Rather than replicate the grittily original descriptions of ground-down refugees found in novels, such as Cormac McCarthy’s The Road – “Creedless shells of men tottering down the causeway like migrants in a feverland” – Popoola and Holmes tell it straight, and in doing so get quickly to the heart of the matter.

By rights these stories should be blighted by moments of tendentiousness: during low ebbs or bouts of injustice we should discern hints of polemic, ripples of authorial condemnation or blasts of anger. But both writers hold back and allow their characters to speak for themselves and display, unmediated, their pain, grievances, misplaced hopes or stoic determination.

In her introductory comment, Ziervogel also writes that this book will “take seriously the fears of people in this country who want to close their borders.” Breach is therefore a bridge, one that spans both sides of a difficult debate and encourages reasoned and proactive discourse. Tough and tender, subtle yet hard-hitting, these compelling stories matter, and with luck will make a difference.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here