The Rosetta spacecraft has crash landed onto the surface of the distant comet it has been exploring for the past two years.

European Space Agency (Esa) controllers burst into applause when the crunch ending to the £1 billion mission was confirmed at 12.20pm, UK time.

Rosetta had already been lying in its lonely resting place 485 million miles away on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for nearly an hour, because of the 40 minutes it took for radio signals travel to Earth.

A decision was taken to carry out the "controlled impact" because the comet is taking Rosetta so far from the Sun that soon its solar panels will not be able to generate sufficient power.

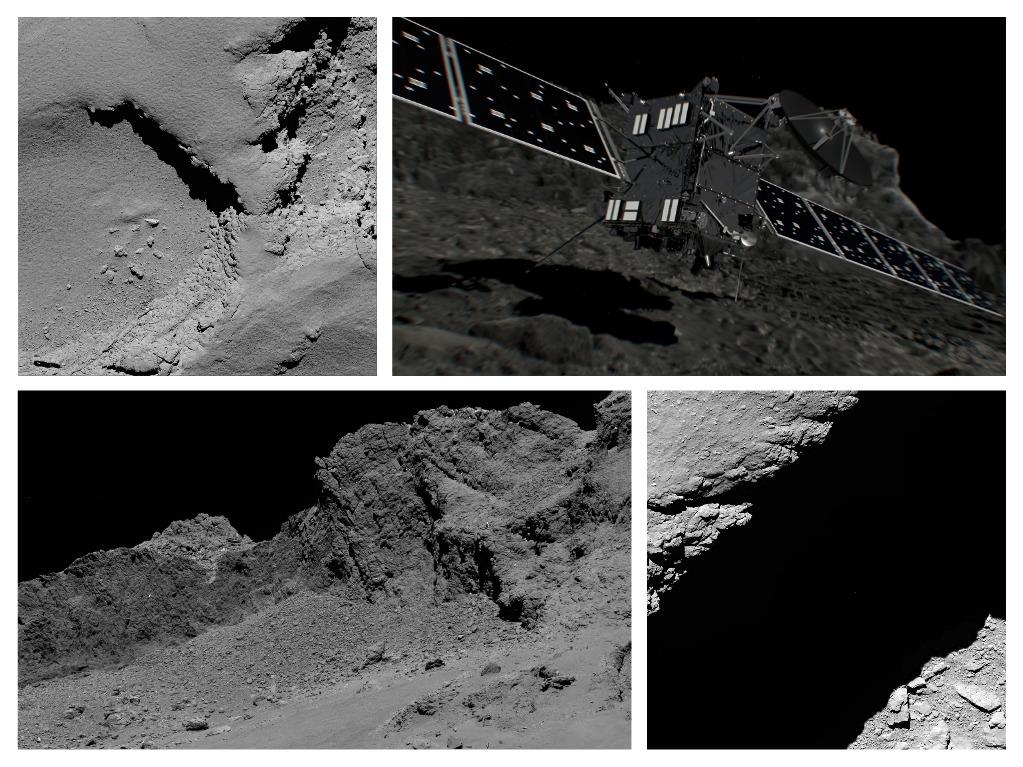

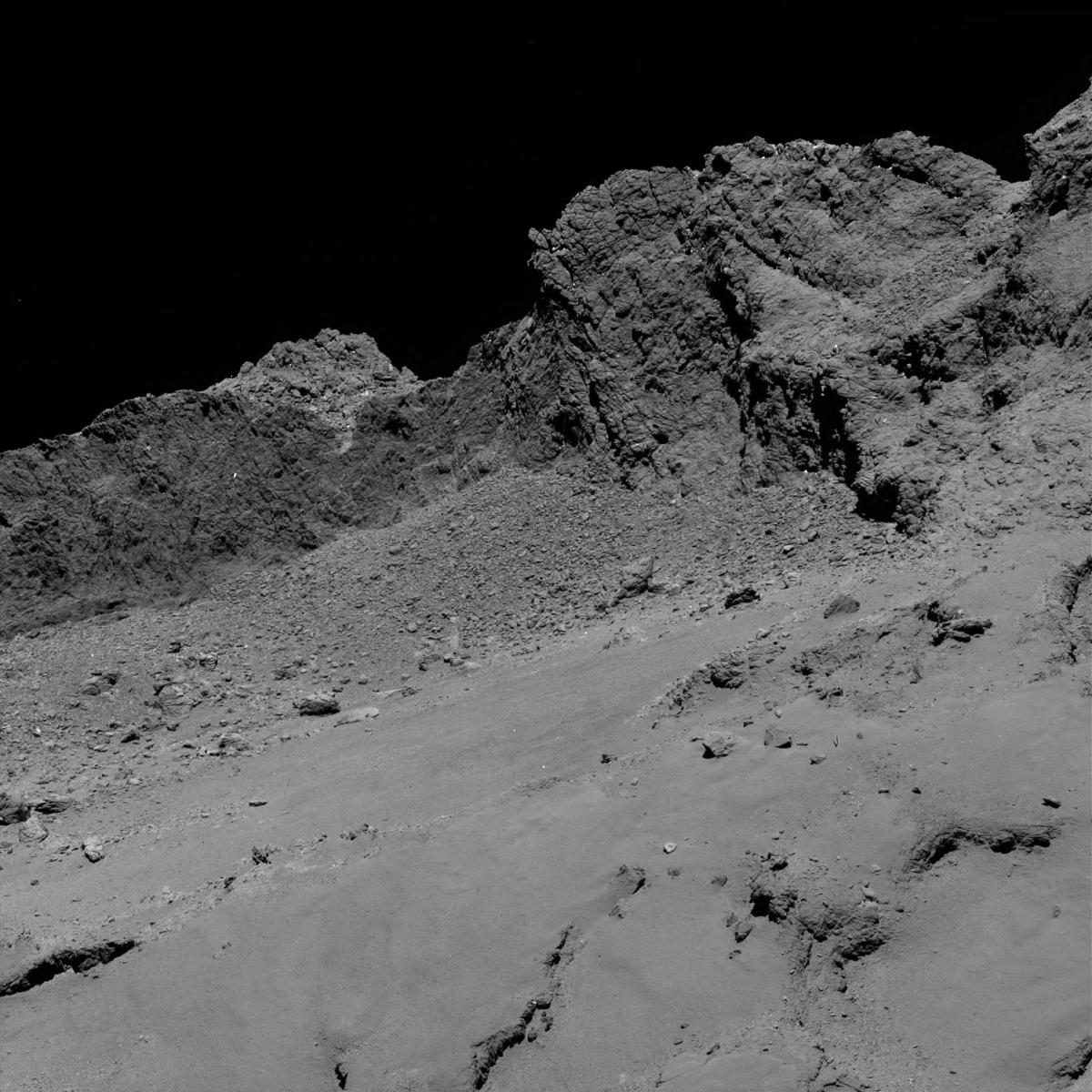

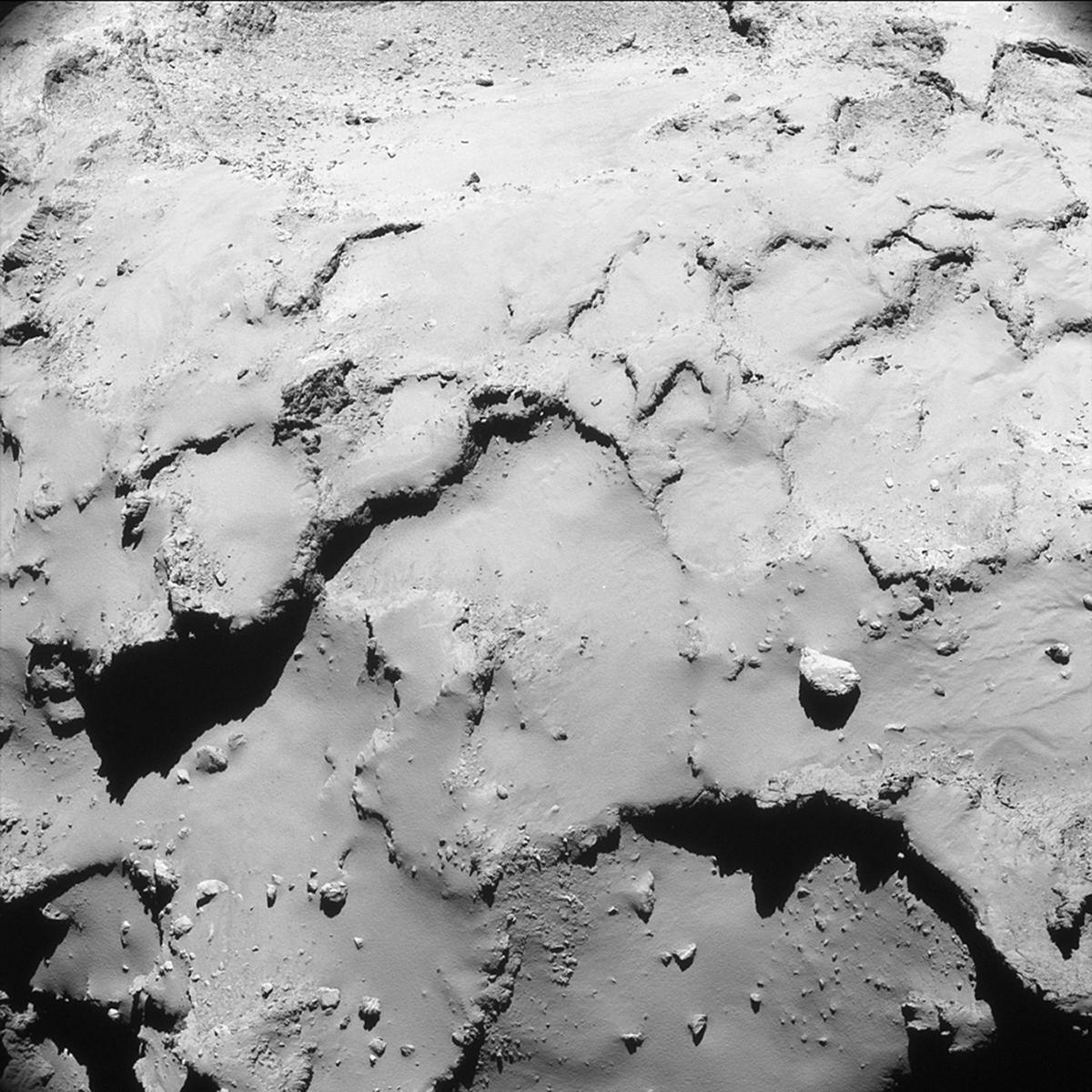

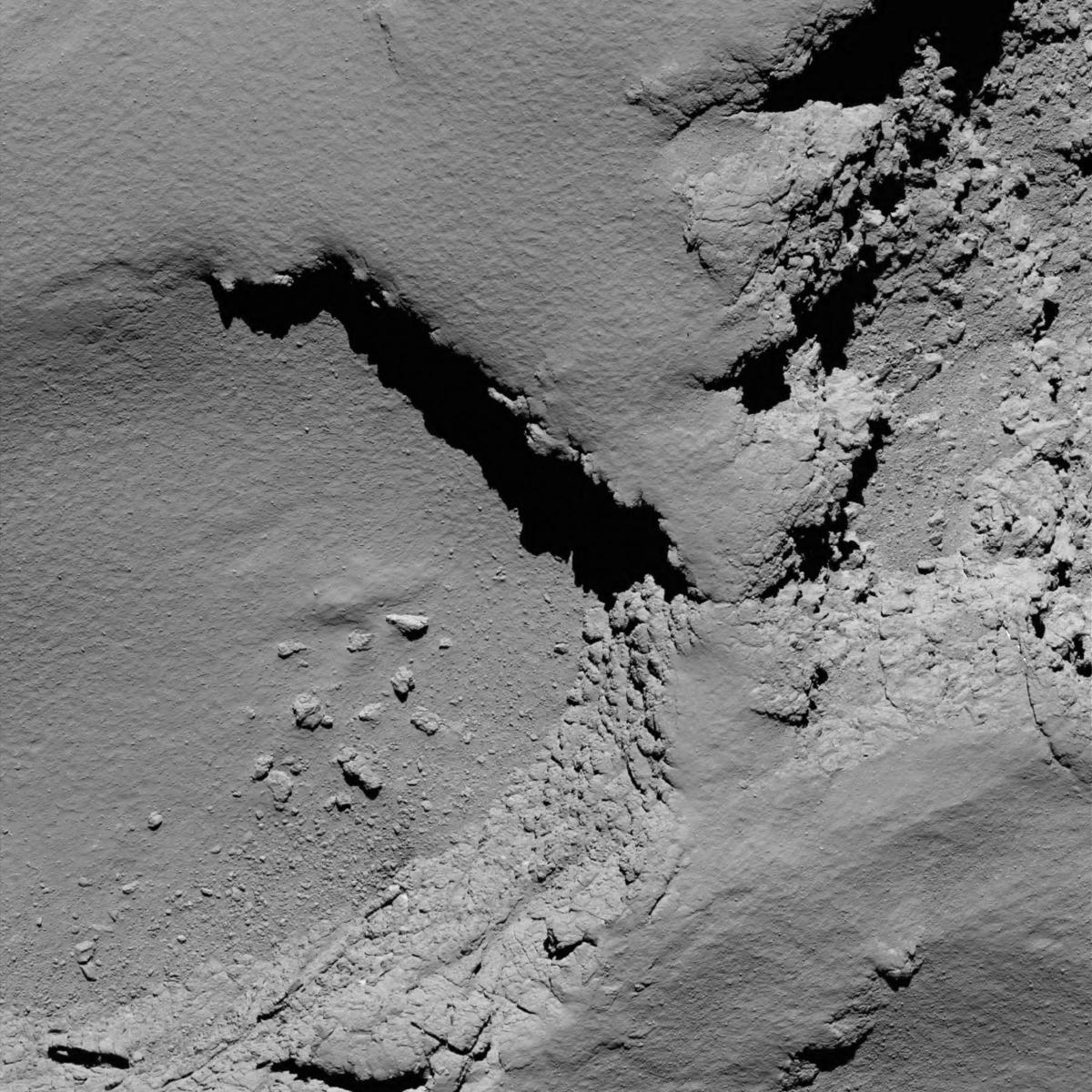

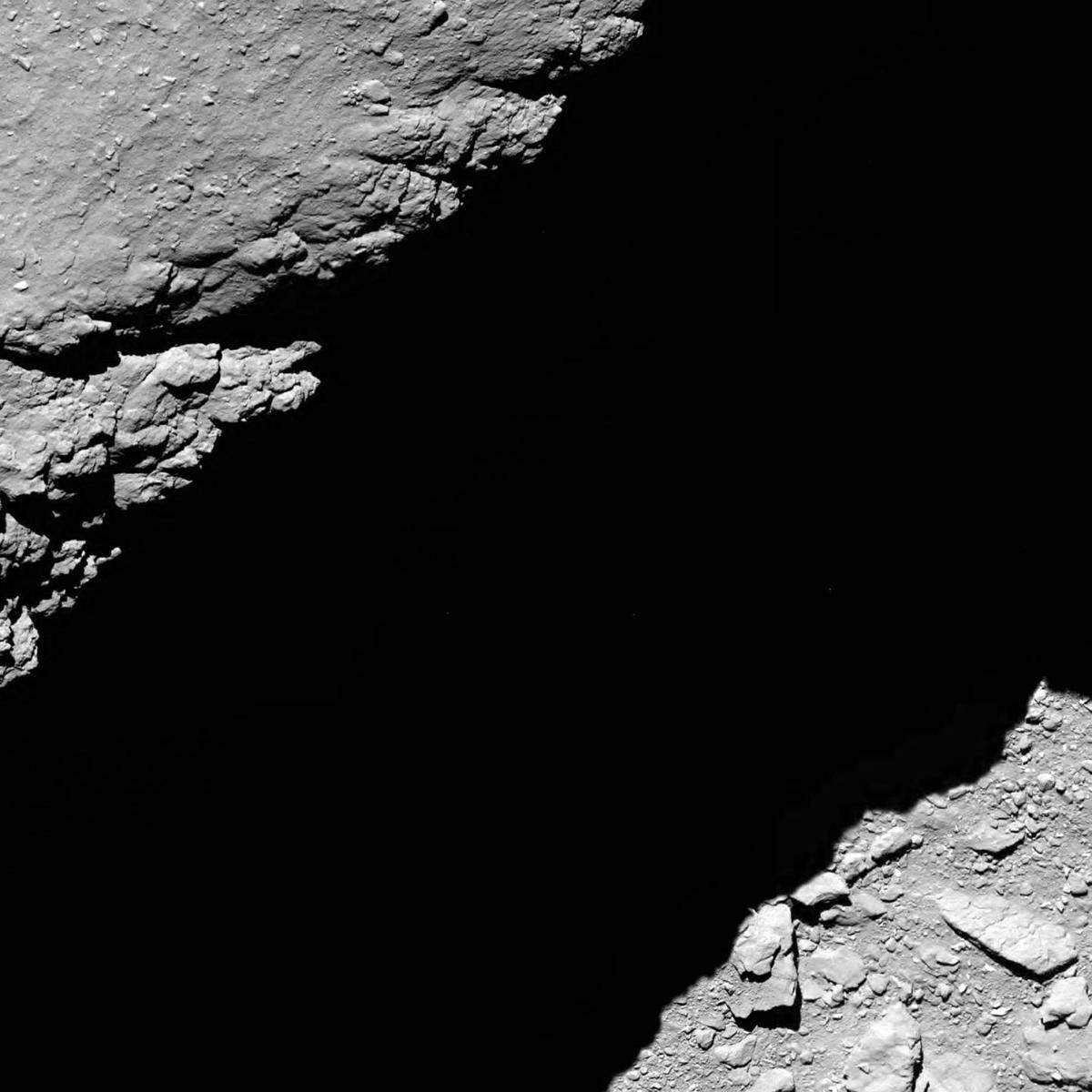

The spacecraft came down in the rugged Ma'at region of the comet, which is littered with boulders and deep active pits known to produce jets of gas and dust.

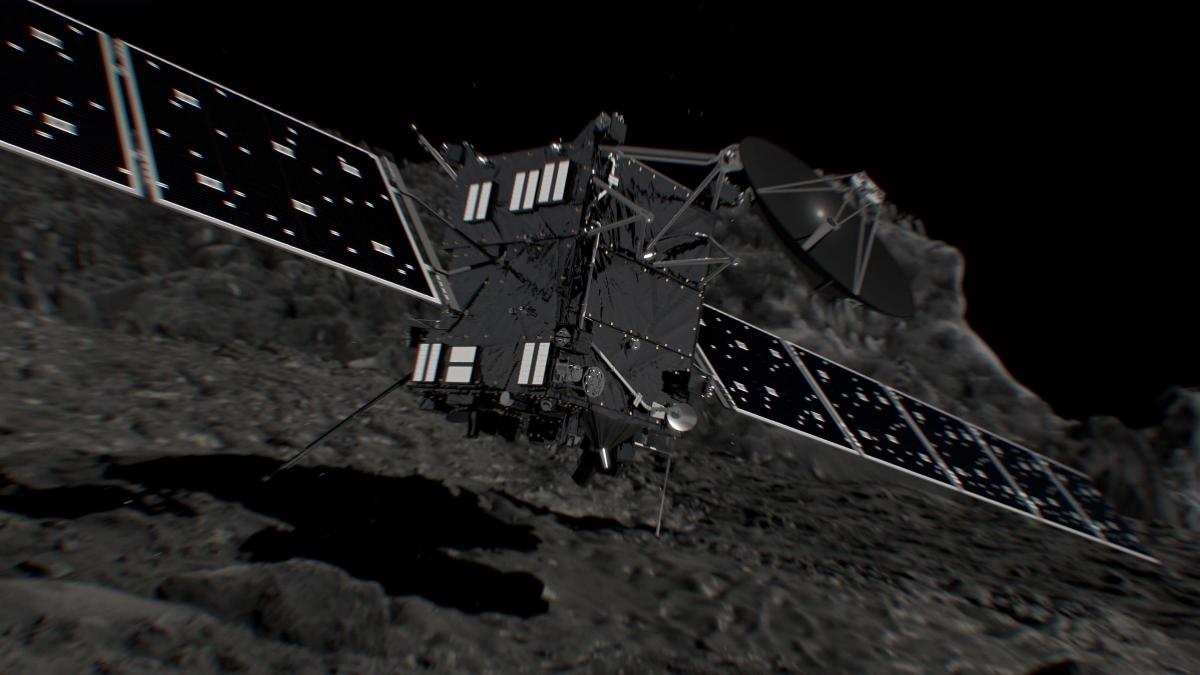

Despite travelling at just 1.1mph the craft was not designed for landing and had no chance of survival.

Esa's head of mission operations Paolo Ferri said: "I think everybody's very sad. On the other hand the end of the mission had to come. It was a spectacular way to do it, and we're quite convinced it was the right thing to do."

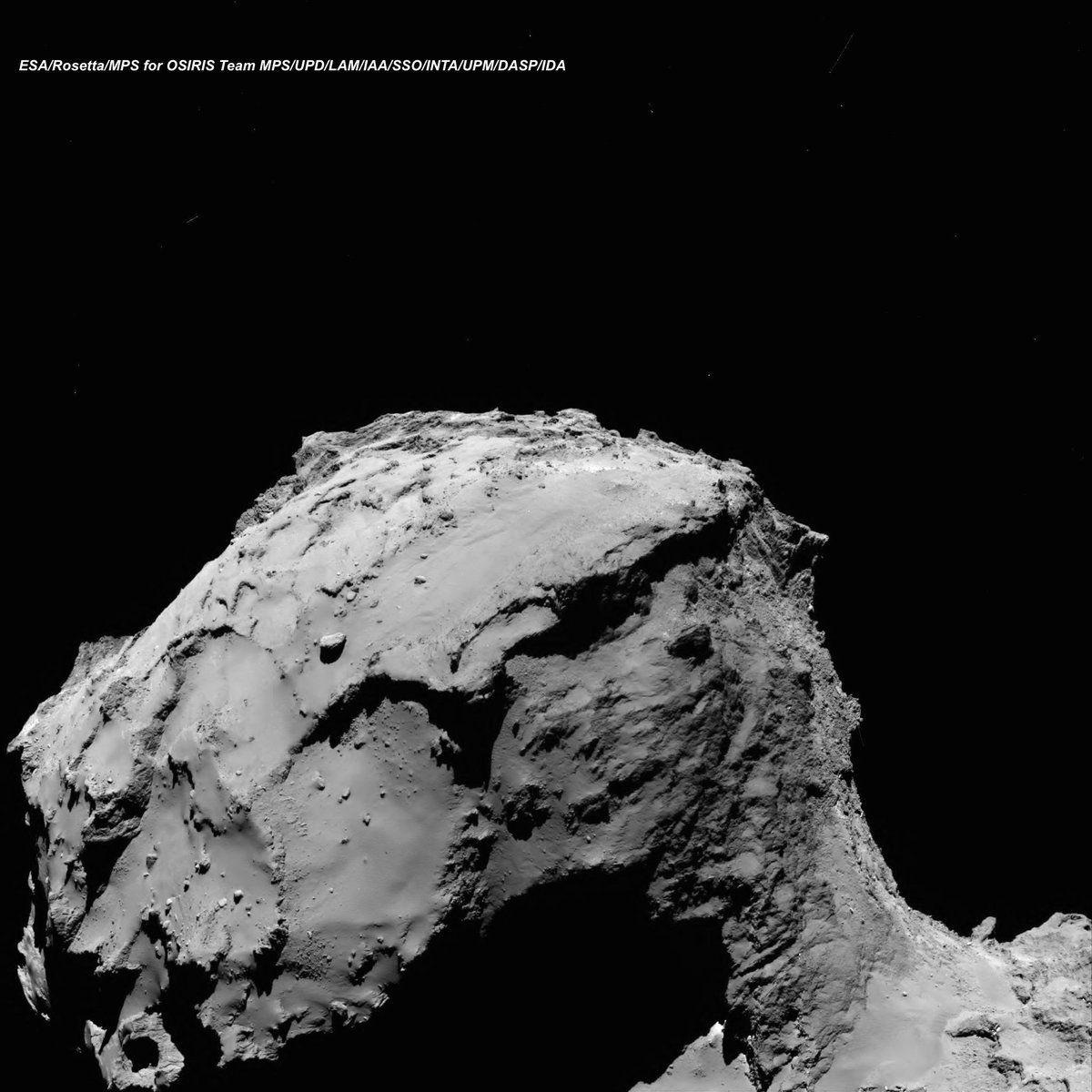

Scientists chose to crash Rosetta on the smaller of the three-mile-long rubber duck-shaped comet's two lobes, just a few kilometres from where its tiny lander Philae is lodged in a deep crevice.

Rosetta reached comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on August 6, 2014, after an epic 10-year journey across four billion miles of space.

The spacecraft and its lander, which bounced onto the surface of the comet on November, 2014, have produced a wealth of data providing valuable clues about the origins of the solar system and life on Earth.

Key discoveries include an unusual form of water not common on Earth and carbon-containing organic molecules that are the building blocks of life.

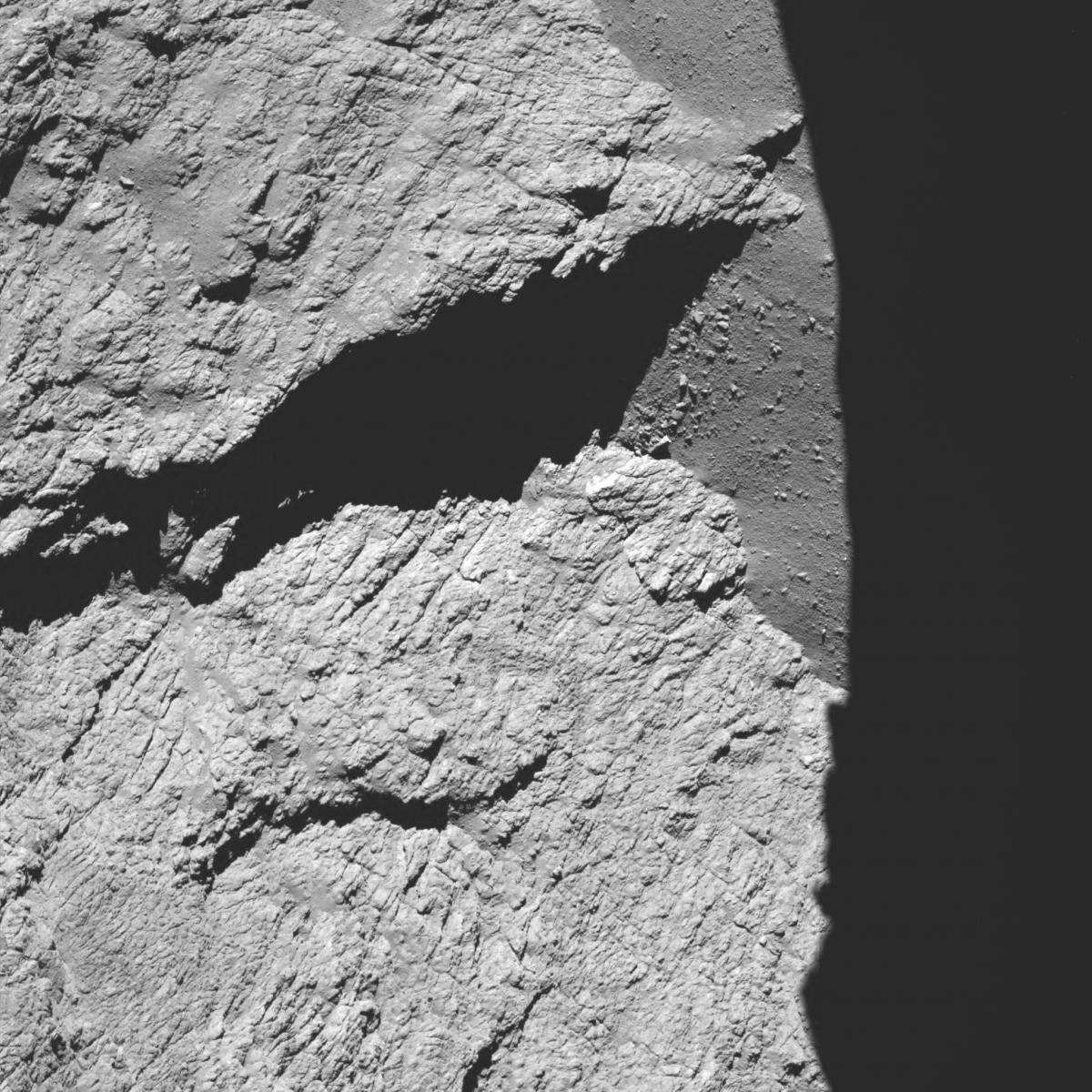

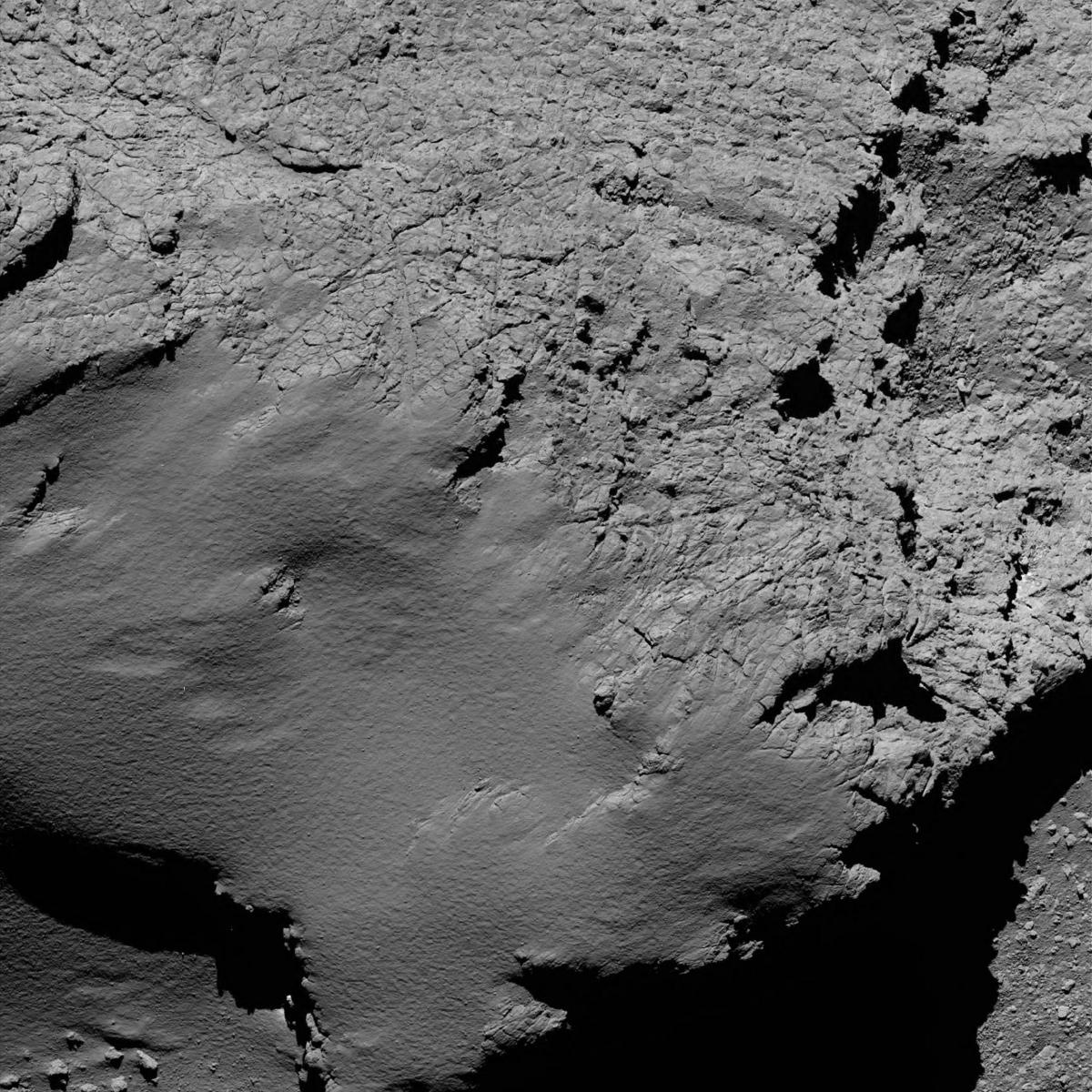

As Rosetta closed in on the comet its cameras sent back a series of dramatic crystal clear images of the crash site, on the edge of a giant pit named Deir El-Medina.

At the same time, its instruments were busy analysing dust and gas close to the surface of the comet.

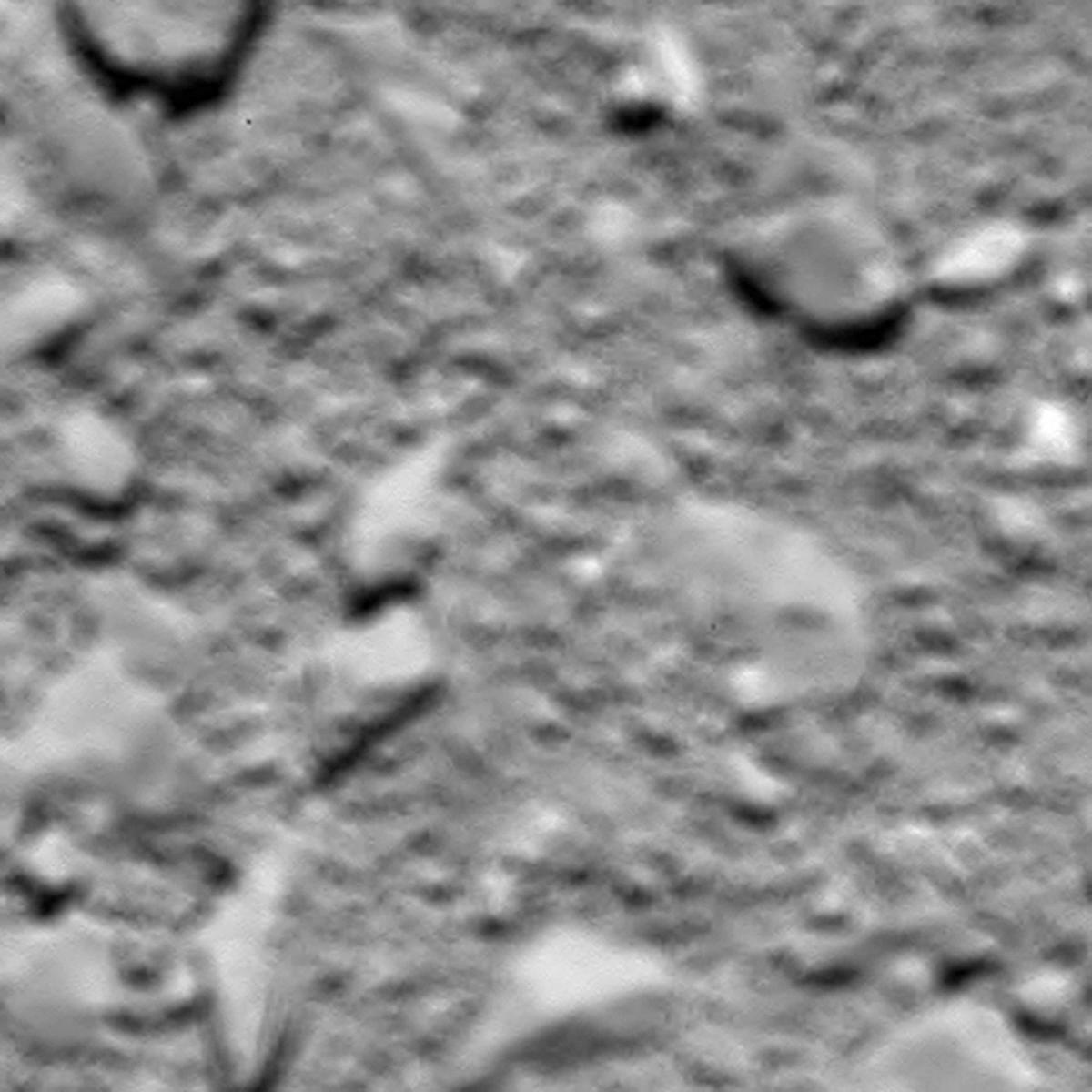

A final slightly blurred image was captured when the spacecraft was just five metres from impact. It showed a rough dusty surface strewn with rocks.

Scientists hope the close-up pictures will help them understand how the comet, thought to have been created by the collision of two separate objects, was formed.

Earlier British planetary scientist Professor Monica Grady, from the Open University, who was closely involved in the design of the Philae lander, said she had "very mixed feelings" about the death of Rosetta.

She told BBC News: "It's been a fantastic mission, but it's time now to move on to the next one.

"It's been a tremendous achievement by the European Space Agency, it's been absolutely amazing."

The crash was carefully orchestrated from the European Space Operations Centre (Esoc) in Darmstadt, Germany.

Controllers set Rosetta on its final journey by executing a "collision manoeuvre" with a small rocket burn at 9.48pm on Thursday night.

From then on there was no turning back.

Final commands to the orbiter - 249 lines of instructions - were transmitted at 5.40am on Friday.

Mission controllers knew the end had come when radio communication with Rosetta was lost.

A note signed by the team and left on the main control room door at the European Space Operations Centre said: "Farewell Rosetta! We will miss you."

Rosetta's British project scientist Dr Matt Taylor, said one of the big surprises was the shape of the comet.

Speaking from Darmstadt, he said: "We've seen comets like that before but this duck was striking. It was formed by two smaller comets colliding at low velocity. We then started to look deeper into it, this dark object, covered in dust, full of organics.

"The implications are all over the place. The fact that we found water there, but it wasn't the same as (on) Earth. But, fundamentally important, going back to the organics again, this stuff could have been delivered by comets to the Earth and formed the ingredients for life, and how that started. It's brilliant."

Among the molecules discovered by Rosetta was the amino acid glycine, a common building block of proteins, the raw material of living organisms on Earth.

Dr Taylor added: "Rosetta's blown it all open, it's made us have to change our ideas of what comets are, where they came from, and the implications of how the solar system formed and how we got to where we are today.

"We have only just scratched the surface. We have decades of work to do on this data. The spacecraft may end, but the science will continue."

Dr Taylor said it was important to remember that the mission consisted of both Rosetta and the Philae lander.

Philae made its bumpy landing on November 12 2014, after failing to anchor itself on to the comet's surface.

It bounced twice and ended up lying crookedly in a dark crack, unable to drill into the ground but still capable of sniffing the surrounding atmosphere.

After maintaining sporadic contact with the lander, Esa switched off Rosetta's radio link with Philae in July this year.

Philae's precise location was only discovered on September 2 when Rosetta spotted the craft at a location on the comet's smaller lobe later named Abydos.

Live video streamed from Darmstadt showed mission controllers clapping and hugging each other when it became clear Rosetta had hit the comet surface.

After a short delay, mission manager Patrick Martin confirmed the end of the spacecraft.

He said: "This is it. I can announce full success of this historic descent of Rosetta towards 67P, and declare hereby the mission operations ended for Rosetta."

Esa's director general Johann-Dietrich Woerner said: "Rosetta has entered the history books once again. Today we celebrate the success of a game-changing mission, one that has surpassed all our dreams and expectations, and one that continues Esa's legacy of 'firsts' at comets."

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel