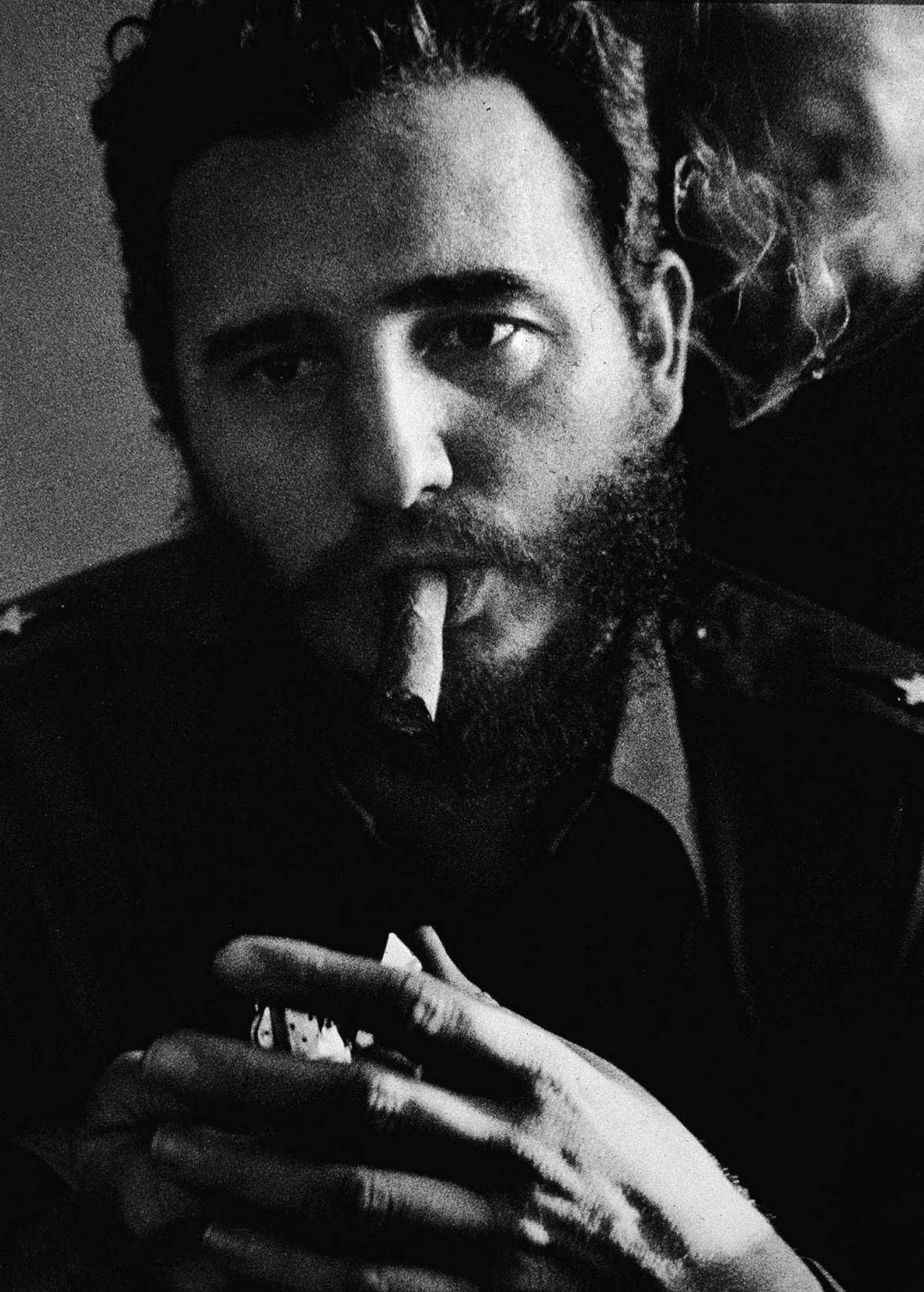

HE was without doubt one of the most colourful, controversial and towering figures of modern times. Often rumoured, now confirmed: Fidel Castro, Cuban revolutionary leader, politician, marathon talker and iconic cigar smoker died late on Friday night.

“I’ll be 90 years old soon,” Castro said at a Communist Party congress in April. “Soon I will be like all the rest. Our turn comes to all of us, but the ideas of the Cuban communists will remain as proof that if one works with fervour and dignity, they can produce the material and cultural goods that human beings need and that need to be fought for without ever giving up.”

Fidel Castro’s life was the epitome of someone who never gave up.

“I began the revolution with 82 men. If I had to do it again, I would do it with 10 or 15 and absolute faith. It does not matter how small you are if you have faith and a plan of action,” he was quoted as saying in 1959, after his successful overthrow of President Fulgencio Batista’s regime.

Castro might not have been a man who ever gave up, but inevitably time caught up with him on Friday.

Wearing an olive coloured military uniform of the kind Fidel made de rigueur for decades, his brother, President Raul Castro appeared on state television to announce the death of Cuba’s revolutionary hero.

“The commander in chief of the Cuban revolution died at 22:29 hours this evening,” Raul said, his voice shaking with emotion.

He ended the announcement by shouting the revolutionary slogan: “Hasta La Victoria Siempre” -Towards victory, always.

Known to most Cubans as “El Comandante” - or simply “Fidel” - Castro built a communist state on the doorstep of the United States and for five decades defied US efforts to topple him.

There were said to be many covert CIA assassination attempts made against him during that time. The agency reportedly deployed everything from exploding cigars to a bacterium infected scuba diving suit along with a booby-trapped conch placed on the sea bottom aimed at killing Castro who was a keen diver.

In the end, he appears to have died of natural causes having been in poor health since an intestinal ailment that nearly killed him in 2006, before he formally ceded power to his younger brother Raul two years later.

For most Cubans, Fidel Castro has been the ubiquitous figure of their entire life. But the man who famously declared, “history will absolve me” leaves a divided legacy.

While many still revere him and share his faith in a communist future, others see him as a tyrant and feel he drove the country to ruin. Those conflicting views were evident on the streets of Havana and Miami as news of his death broke.

In the Cuban capital, Havana, many residents were reported to have reacted with sadness. In Miami however, where many exiles from the Communist government live in the “Little Havana” neighbourhood, attitudes were very different.

There, thousands of people banged pots with spoons, waved Cuban flags in the air and whooped in jubilation on Calle Ocho - 8th Street, at the heart of the neighbourhood.

“The dictator Fidel Castro has died, the cause of many deaths in Cuba, Latin American and Africa,” Jose Daniel Ferrer, leader of the island's largest dissident group, the Patriotic Union of Cuba, said on Twitter.

In Cuba itself, however, the mood was sombre and reflective.

“I am very upset. Whatever you want to say, he is public figure that the whole world respected and loved,” Reuters news agency reported one Havana student, Sariel Valdespino, as saying, summing up the response of many Cubans.

Another young Cuban, Carlos Rodriguez, 15, was sitting in Havana’s Miramar neighbourhood when he heard that Castro had died.

“Fidel? Fidel?” he said, slapping his head in shock. “That’s not what I was expecting. One always thought that he would last forever. It doesn’t seem true.”

Tributes poured in from world leaders including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Venezuela’s socialist President Nicolas Maduro, who said, “revolutionaries of the world must follow his legacy”.

Born Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz on August 13, 1926 in Biran, a village in eastern Cuba, Castro and his six siblings enjoyed a childhood of prosperity. Castro was a rebel from early childhood. By the time he was 13 he was agitating for his first insurrection, accusing his father Angel of exploiting sugarcane workers on his farm.

Later he worked as a lawyer in Havana after his studies, often serving poorer clients.

He was already politically active as a student, and his 1952 run for parliament came to nothing when US-backed Fulgencio Batista took power in a coup. Castro made it his mission to overthrow Batista.

Angry at social conditions and Batista’s dictatorship, Castro launched his revolution on July 26 1953, with a failed assault on the Moncada barracks in the eastern city of Santiago.

He was sentenced to 15 years in prison, but was released in 1955 after a pardon that would come back to haunt Batista.

Castro then went into exile in Mexico and rallied like-minded rebels around him, among them Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

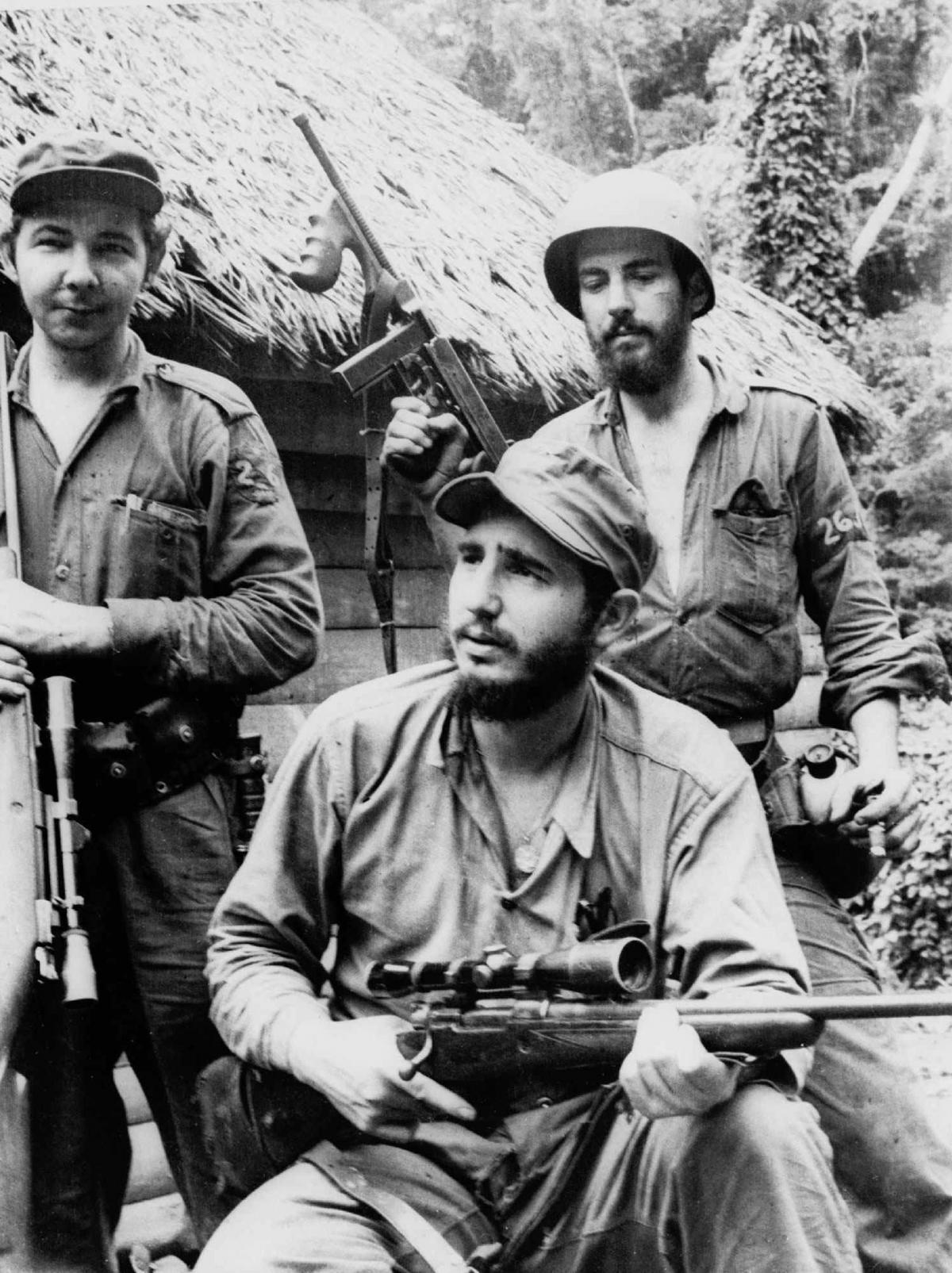

By December 1956, Castro and his 81 guerrillas sailed to Cuba aboard an overloaded yacht called “Granma”.

Only 12, including him, his brother and Guevara, escaped a government ambush when they landed in eastern Cuba.

Later Raul Castro would recount those difficult, dangerous, but heady times.

“On December 18, 1956, Fidel and I were in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra, in a place called Cinco Palmas. After our first hug his first question was, ‘How many rifles do you have?’ I answered five. And he said, ‘I have two. That makes seven. Now we can win the war’.”

Taking refuge in the rugged Sierra Maestra range, they built a force of several thousand fighters who, along with urban rebel groups, defeated Batista’s military in just over two years.

Tens of thousands spilled into the streets of Havana to celebrate Batista’s downfall and catch a glimpse of Castro as his rebel caravan arrived in the capital on January 8, 1959.

His speeches that day were typical of a man renowned for his capacity to talk. Some speeches would last up to six hours and became part of the narrative of Cuban life.

His 269-minute speech to the UN General Assembly in 1960 set the world body’s record for length that still stood more than five decades later.

Alongside the oratory and within months of taking power, Castro was imposing radical economic reforms. Members of the old government went before summary courts, and at least 582 were shot by firing squads over two years.

Transforming Cuba from a playground for rich Americans into a symbol of resistance to Washington, Castro would outlast nine US presidents in power.

He also fended off a CIA-backed invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 as well as countless assassination attempts.

But many Cubans saw his rule as oppressive and in 1964, Castro acknowledged holding 15,000 political prisoners. By now, hundreds of thousands of Cubans had fled mostly to Miami, including Castro's daughter Alina Fernandez Revuelta and his younger sister Juana.

With Castro in total control of the Caribbean island, his socialist plans put him increasingly at odds with the United States and pushed him closer to the Soviet sphere of influence.

Cuba’s alliance with the Soviet Union brought in $4 billion worth of aid annually, including everything from oil to guns, but also provoked the 1962 Cuban missile crisis when Washington discovered Soviet missiles on the island.

Convinced that the US was about to invade Cuba, Castro urged the Soviets to launch a nuclear attack. In the end cooler heads prevailed. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and US President John F Kennedy agreed the Soviets would withdraw the missiles in return for a US promise never to invade Cuba.

By now, with Cuba having moved closer to the Soviet bloc Washington began working to oust Castro, cutting US purchases of sugar, the island's economic mainstay. Castro, in turn, confiscated $1bn in US assets.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, an isolated Cuba fell into a deep economic crisis that lasted for years and was known as the “special period”. Food, transport and basics were scarce and energy shortages led to frequent and lengthy blackouts.

Castro undertook a series of tentative economic reforms to get through the crisis, including opening up to foreign tourism. Speaking to journalists in 1990 about the development of tourism Castro admitted the country was on new ground.

“We do not know anything about this. We, gentlemen, to tell the truth, do not even know what to charge.”

But Castro forever dogged and determined, stuck to his socialist vision.

His government improved the living conditions of the very poor, achieved health and literacy levels on a par with rich countries and rid Cuba of a powerful Mafia presence.

Such achievements did not go unnoticed around the world.

“From its earliest days, the Cuban revolution has been a source of inspiration… we admire the sacrifices of the Cuban people in maintaining their independence and sovereignty in the face of the vicious imperialist and orchestrated campaign to destroy the awesome force of the Cuban revolution,” said Nelson Mandela in a 1991 speech.

By the time Castro resigned 49 years after his triumphant arrival in Havana, he was the world’s longest ruling head of government, aside from monarchs.

In his final years, he no longer held leadership posts. He wrote commentaries on world affairs for the state newspaper Granma and occasionally met with foreign leaders, but he lived in semi-seclusion.

He never tired, though, of having a go at his arch-enemy the United States.

“The Yankees will never end their control of the earth, the water, the mines and our lands’ natural resources,” he wrote in Granma in 2012.

Raul, meanwhile, was beginning to take over the reins of power. Appointed by parliament to serve as both head of state and government, as well as Communist Party chief, he began to open up the country, and US-Cuban relations, frozen for nearly five decades, began to thaw.

Fidel having proclaimed “socialism or death” earlier in his life, said little about these steps towards normalisation between the two countries and it was never clear if he fully backed his brother’s reform efforts.

Some Cuba watchers believed his mere presence kept Raul from making greater reforms and changing things more rapidly, while others saw him as either quietly supportive or increasingly irrelevant.

The question now is what will be the impact of Castro’s death and how might it affect relations with the US?

Certainly most diplomats in Havana do not expect a huge change in the short term, but the death will underscore the need for the revolutionary generation to move on and could embolden democracy activists. For the Castro family itself Raul is expected to hand over power at the end of his current term, but the ruling family have many other powerful positions in government and business that they will no doubt maintain.

As for relations with the US, his death will mean little given that he was already side-lined in later life as Raul handled affairs. The election of Donald Trump is likely to be of far more significance in relations between the two countries.

Yesterday, in marking Castro’s death the Cuban government declared nine days of national mourning during which all public events and activities will cease and the national flag will fly at half-mast on public buildings.

As world and political leaders continued to respond to news of Castro’s passing, Britain’s former Labour cabinet minister, Peter Hain, summed up the contradictory and divisive legacy that the Cuban leader left behind.

“Although responsible for indefensible human rights and free speech abuses, Castro created a society of unparalleled access to free health, education and equal opportunity, despite an economically throttling US siege,” said Hain.

Hain, who was a noted anti-apartheid campaigner, also paid tribute to Castro’s role in deploying Cuban troops who “inflicted the first defeat on South Africa’s troops in Angola in 1988, a vital turning point in the struggle against apartheid”.

Controversial as he was, Fidel Castro, revolutionary leader of Cuba, made a profound impact on the world.

“A revolution is not a bed of roses. A revolution is a struggle between the future and the past,” he said in 1959 after ousting the Batista regime.

Loved and loathed in equal measure, Fidel Castro was nevertheless a political giant of the 20th century.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel