Truevine – Two Brothers, A Kidnapping And A Mother's Quest:

A True Story Of The American South

Beth Macy

Macmillan, £18.99

IN AMERICA in 1900 there were 98 travelling circuses, the biggest hauling three or more rings, hundreds of animals and up to 1000 employees across the country in specially commissioned trains. In bigger places the circus stayed a week. In smaller ones just a night, with the roustabouts rising early and working late to put up and take down the tents as the “lot lice” – carnie slang for punters – looked on in wonder.

In most circuses, a highlight was the sideshow. Here is where you'd find giants, dwarves, strong men and bearded ladies – commonly known as freaks – alongside more esoteric fare like Zip, the Man Monkey, who wore a fur suit, ate cigars and raw meat and was supposedly found walking naked on all fours near the Gambia river. In fact his name was William Henry Johnson, he was the son of newly-freed slaves and he was “discovered” in New Jersey in 1860 aged four.

But for Darwin-obsessed Americans for whom slavery was still a living memory and racism still a potent force, he was a curio they would pay to see. That meant anyone like him who was different – Zip had a form of microchephaly which resulted in abnormal smallness of the head – had a price tag that so-called “freak hunters” could exploit.

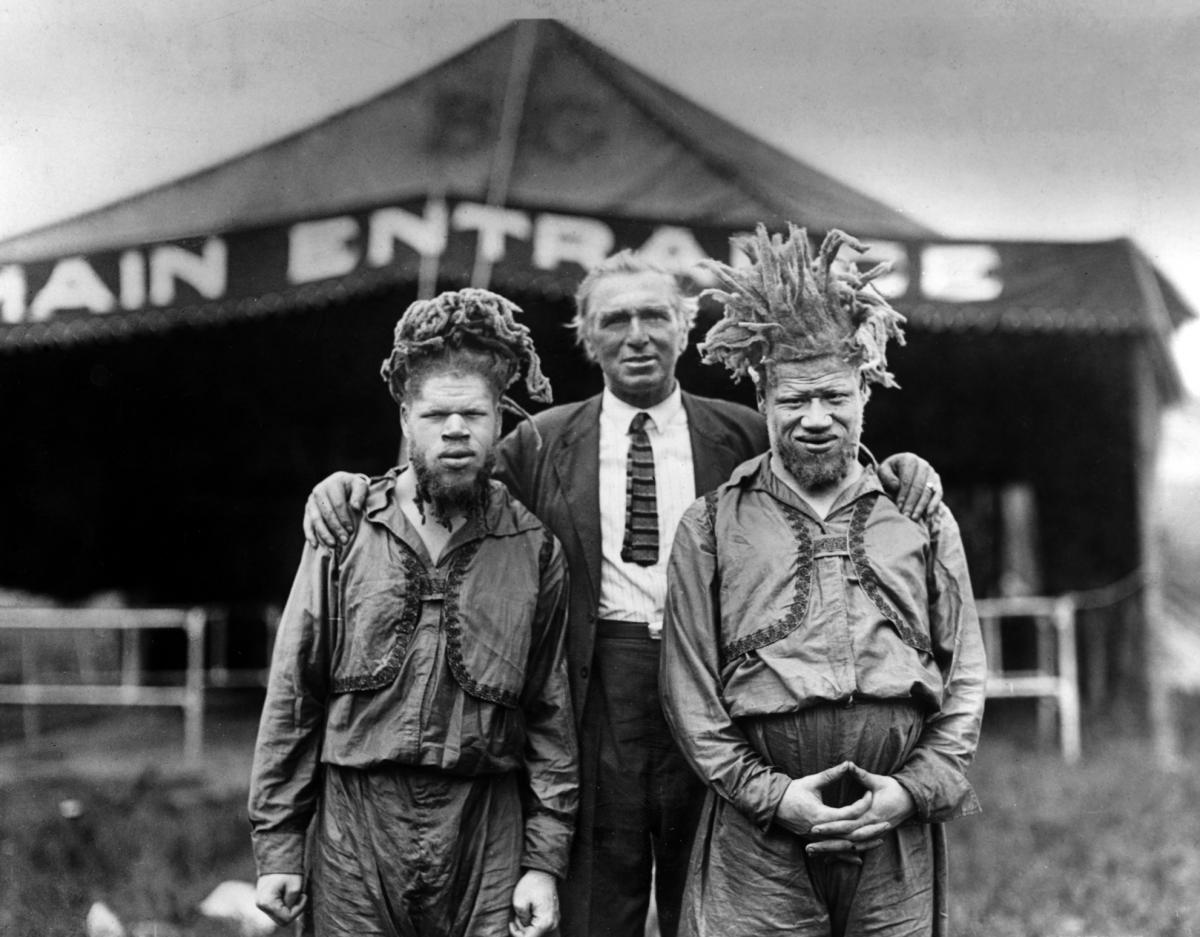

Dreadlocked African-American albino brothers George and Willie Muse were two such unfortunates and it's their story that Beth Macy tells here. She begins with their alleged kidnapping from their home in rural Truevine, Virginia some time around 1899, and tracks them through a long career in carnivals and circus sideshows in which they were christened Iko and Eko, billed variously as “the Ambassadors from Mars” or “the Sheep-Headed Cannibals”, written about in The New Yorker (“good examples of contented freaks”) and even sent to London to perform.

Treated as property by their grasping and unscrupulous manager Candy Shelton, and exhibited accordingly, they were dramatically re-claimed by their mother, Harriet Muse, while performing for the famous Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus in her home city of Roanoake, Virginia in October 1926. By this point the brothers' back story had been embellished further and they were supposed to have been discovered by John Ringling himself, floating on a raft off the coast of Madagascar.

Not a word of it is true, of course, though as Macy discovers as she digs through archives and court reports and drills down into “more rabbit holes than I can count”, the Muse family myth about a kidnapping isn't quite on the money either.

In fact, it seems that Harriet Muse engaged with Shelton to let the boys join the circus for a short period around 1914, and then completely lost track of them as they disappeared into the world-within-a-world which was the carnival business. She (and they) certainly received no money and it was only after that fateful reunion 12 years later and a hard-fought legal case that earnings began to be paid.

Macy, who started out on the Roanoke Times in the late 1980s and first wrote about the celebrated local brothers in an extensive 2001 article, uses her sleuthing skills as well as extensive interviews with surviving family members and other local contacts to piece together where Willie and George were, and when.

But until the end of the book, when family memories of the centenarian Willie are more cogent, the brothers themselves are a blank space – two vulnerable-looking men peering at a camera in one of the many publicity photographs the circuses produced or, only marginally less troubling, snapped performing songs on stage. Few contemporary accounts from newspapers or magazines are anything other than glib, shallow and racist.

Unsurprisingly, then, Macy never manages to nail down why Harriet let her boys go in 1914, where the kidnapping story came from, or who the boys' real father was (she does discover that Harriet was actually living under the name Cook in 1914). There's also a question over whether or not the brothers were mentally impaired: family lore says no, many contemporary accounts say the opposite. As Macy notes in her afterword, the tale she has told is “imperfect and incomplete”, and likely to stay that way.

But besides telling the story of the brothers' careers and Harriet Muse's attempts to find them (not easy given that all three concerned were illiterate and left no journals, letters or diaries) Macy widens her focus to look at the phenomenon of the circus in early 20th century American culture and, more pointedly, to detail the social, political and economic injustices visited upon southern blacks at least until the early 1960s.

These, in particular, are jaw-dropping. Lynching we know about, but Macy dips into (among many other things) the tradition of “peonage”, or involuntary servitude, which continued at least into the 1920s; and Virginia's active eugenics programme, which disproportionately targeted African-Americans.

In some ways, though, Willie Muse had the last laugh. Brother George died in 1972, but Willie lived to be 108, outlasting 19 US presidents – and everybody who had ever done him wrong.

BARRY DIDCOCK

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here